SYNOPSIS:

“In 1895, in a small village in Japan, the wife of the litter carrier Gisaburo (Takahiro Tamura), Seki (Kazuko Yoshiyuki), has an affair with a man twenty-six years younger, Toyiji (Tatsuya Fuji). Toyiji becomes jealous of Gisaburo and plots with Seki to kill him. They strangle Gisaburo and dump his body inside a well in the woods, and Seki tells the locals that Gisaburo moved to Tokyo to work. Three years later, the locals gossip about the fate of Gisaburo, and Seki is haunted by his ghost. The situation becomes unbearable to Seki and Toyiji when a police authority comes to the village to investigate the disappearance of Gisaburo.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

After graduating from Kyoto University where he studied political history, filmmaker Nagisa Oshima was hired by production company Shochiku and quickly progressed to directing his own movies, making his debut feature A Town Of Love And Hope (1959). The following year he won the inaugural Director’s Guild Of Japan award for Best New Director. The Ceremony (1971) was a satirical look at Japanese attitudes, famously expressed in a scene where a marriage ceremony has to go ahead even though the bride is not present. Released the same year was In The Realm Of The Senses (1971) based on a true story of fatal sexual obsession in thirties Japan. A critic of censorship, Oshima was determined that the film should feature real sex scenes and thus the film had to be transported to France to be processed.

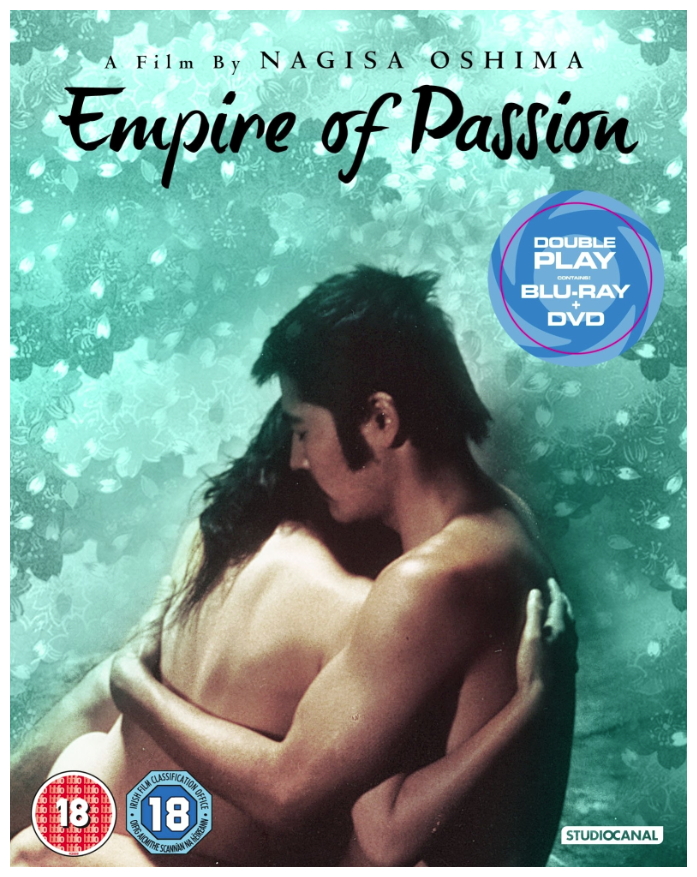

His companion piece to In The Realm Of The Senses, Empire Of Passion (1978), took a more restrained approach to depicting the sexual passions of the two lovers driven to murder, the resulting film winning the Cannes Film Festival award for Best Director. The story focuses on Seki (Kazuko Yoshiyuki) and her younger lover Toyoji (Tatsuya Fuji), who join together in strangling Seki’s husband Gisaburo (Takashiro Tamura), one might suppose that, if she saw what she wanted to see, she would never see him again. On the other hand, he was a good husband, and perhaps she sees what she really wants to see, when she returns home one night to find Gisaburo’s ghost sitting calmly by the fire waiting for her to pour him his sake. She may miss him more than she thought. Japanese customs in a small rural village in 1895 have forbidden her to live with her lover, and she is lonely.

She is upset too, at her daughter’s questions about what has happened to the father (his body is at the bottom of a well), and her story about his seeking work in Tokyo is beginning to wear thin. The villagers are also beginning to gossip. What is remarkable about this tender and lovely film is the matter-of-factness of it all. The ghostly husband goes back to his job as rickshaw driver as if no more needed to be said. The seasons pass in their stately manner, the ghost occasionally reappears, and Seki becomes more distraught. Intimations of a more modern Japanese state appear even in this remote corner, and the village policeman, Inspector Hotta (Takuzo Kawatani) is now convinced that Seki is a murderess. Toyoji sees the ghost too, and this time – just for a moment – it has something of the demonic quality of the traditional vengeful ghosts of Kabuki theatre.

Empire Of Passion is not really a horror film. It’s not only about the constraints that a small, stable, conservative society place upon an obsessive love, but also about being lost (Toyoji, twenty years younger than she, is an ex-soldier who doesn’t quite fit into village life, and is also lonely). The ghost is not threatening but merely a mute reminder of the simplicities of the life that she abandoned for so trivial a reason (he was murdered because she couldn’t bear to reveal to him that she had shaved off her pubic hair in a fit of passion). Finally the lovers go down to the well to retrieve the body, leaves are falling, and Seki is truck blind by some unseen force. When they emerge they are taken by police and tortured. The body is raised from the well, Seki confesses and, just for a moment, Seki can see again.

It is a fine film indeed, and serves as a reminder that ghosts need not be restricted to the conventions of horror cinema. They can symbolise memory and regret as well as menace and revenge. Oshima received worldwide critical success with a film made partly in English, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence (1983), set in a wartime prison camp, starring music legends David Bowie and Ryuicji Sakamoto alongside Takeshi Kitano. The movie has since become a cult favourite. Max Mon Amour (1986), co-written by Jean-Claude Carrière, was a comedy about a diplomat’s wife whose love affair with a chimpanzee is quietly incorporated into an eminently civilised ménage à trois.

For much of the eighties and nineties he served as president of the Director’s Guild Of Japan, suffering a stroke in 1996, but recovered enough to direct the samurai film Taboo (1999 aka Gohatto), set during the bakumatsu era starring Takeshi Kitano with a score composed by Ryuicji Sakamoto. He subsequently suffered more strokes, and Taboo proved to be his final film. Nagisa Oshima passed away 15th January 2013 of pneumonia, aged eighty. I’m sorry to be leaving you with such a bleak and sad image but, be warned, I will not accept that as a valid reason for your not returning next week. I’d miss you too much. So please join me again as I discuss the brutal slashing of budgets and death by a thousand cut corners in Horror News! Toodles!

Empire Of Passion (1978)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews