SYNOPSIS:

“The unassuming, nebbishy inventor Sidney Stratton creates a miraculous fabric that will never be dirty or worn out. Clearly he can make a fortune selling clothes made of the material, but may cause a crisis in the process. After all, once someone buys one of his suits they won’t ever have to fix them or buy another one, and the clothing industry will collapse overnight. Nevertheless, Sidney is determined to put his invention on the market, forcing the clothing factory bigwigs to resort to more desperate measures.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

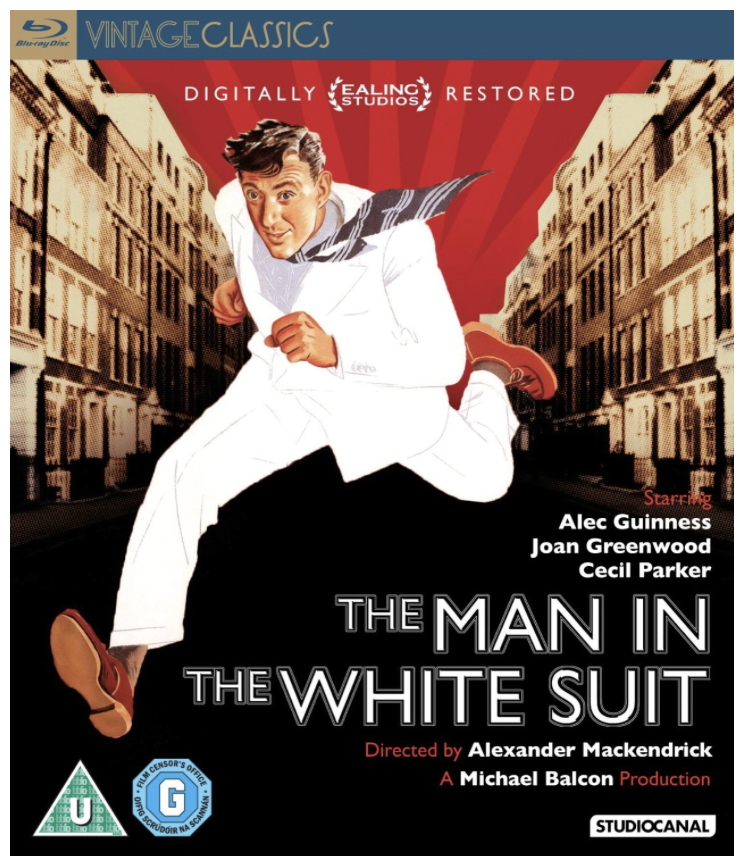

British science fiction films in the fifties followed a path similar to the American, though on a much smaller scale. During the first half of the decade they tended to reflect the underlying fears of the Cold War and it was during this period that the better films were produced. Then, from 1956 onwards, the cycle degenerated into ever cheaper and more perfunctory variations on the monster theme. A typically British science fiction film of the early fifties was The Man In The White Suit (1951). Again it concerns a scientist and his invention but, being produced by Ealing Studios (the company that produced the best of the British post-war comedies) its treatment of a familiar science fiction plot – the laboratory-created ‘thing’ that causes nothing but trouble – is produced in the inimitable Ealing style rather than that of a conventional science fiction film. Ealing (established in 1931) is the oldest continuously working film studio in the world, best known for a number of classic movies like Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949), Passport To Pimlico (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955).

Textiles scientist Sidney Stratton (Alec Guinness) invents an artificial fibre that never wears out and actually repels dirt. To prove its unique qualities he makes himself a shining white suit that retains its pristine condition throughout the film. His invention causes alarm to both the clothing manufacturers and their workers, who fear its effects on their industry. Textile workers worry that such a material will cause them to lose their jobs, and industrialists worry what it will do to prices. Realising that their livelihoods depend on ‘planned obsolescence’, management and labour join forces to stop Stratton from leaking news of his invention to the press. It comes as no surprise that the industrialists are portrayed as devious men who couldn’t care less about the practical value of Stratton’s invention if it means their profits will go down. In fact, the film confronts problems that are seldom tackled in more overtly serious science fiction movies.

The script delivers its hardest punch to the workers, who aren’t grateful to Stratton either. When the chips are down, their actions turn out to be as ugly and as selfish as their managers – which is what happens in the most famous of Britain’s labour-management comedies I’m All Right Jack (1959). Various attempts are made to suppress the new material, all of which are resisted by the inventor, until finally he is cornered by an angry mob in the street and his suit – suddenly and symbolically – begins to disintegrate. Everyone is relieved that the material is not the perfect substance it was believed to be, with the exception of the disillusioned inventor. But Stratton is only momentarily dismayed and the film ends with him happily planning a second attempt. Alec Guinness is wonderfully naive and touching in his part, which involves a protracted chase sequence as everyone tries to catch him, and is ably supported by Cecil Parker, Michael Gough and Ernest Thesiger.

Basically a satire, what makes this science fiction film unusual is that it is not really anti-science: Neither the scientist nor his creation is the target for the film’s gentle ridicule, but rather the people around him, who react to something new with fear and ignorance. Photographed by Douglas Slocombe near the beginning of a brilliant career spanning half a century and eighty classic films, and the script, adapted by director Alexander Mackendrick and John Dighton, was based on Roger MacDougall‘s novel and stage play. This cynical film shows disenchantment with selfish British workers, who are supposed to be the consumer’s watchdogs – since they are consumers themselves – but are resistant to making better, cheaper products because of job insecurity. Scientist Stratton cares more about his work than pretty Daphne (Joan Greenwood), and has absolutely nothing in common with common men (he’s pragmatic rather than humanistic). This means that there are no characters (no worker, no humanist) left to represent the bottom-line consumer in industry.

The strange noises made by the laboratory apparatus were created by sound editor Mary Habberfield and produced for the sound track by a tuba and a bassoon. The sounds (described on the record label as ‘Guggle-Glub-Guggle’) were set to music by Jack Parnell and released as The White Suit Samba with lyrics by T.E.B. Clarke. The BBC owned Ealing Studios from 1955 until 1995 and the studio has now resumed releasing films under its own name, including the revived Belles Of St. Trinian’s (1954) franchise. In more recent times the studio is known for films like The Importance Of Being Earnest (2002), Shaun Of The Dead (2004), Burke And Hare (2010), The Theory Of Everything (2014), The Imitation Game (2014), and Burnt (2015), as well as the popular television series Downton Abbey, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll quickly wrap up this article and politely request your company next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier again with another feather plucked from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

The Man In The White Suit (1951)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews