SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Grace Collier is a columnist with the Staten Island Panorama. She generally works on fluff pieces, but on occasion is allowed to do hard hitting stories which she prefers. From her apartment window one morning, she sees what she is certain is the stabbing murder of a black man by a white woman in an apartment across the way, the black man, seeing her, who tried to scrawl the word ‘help’ in his own blood on the window. Reporting what she saw to the police, Grace gets little help from them, with who she has a bad relationship if only because of previous stories she has written on police brutality and racism. When the police and Grace arrive at the apartment in question, they find no dead body, no blood, and no woman matching who Grace saw commit the murder. All they find is the tenant, Danielle Breton, a young French-Canadian model/actress, who is visited by her soon to be ex-husband, Emil Breton. However, what Grace saw truly did happen, the dead man being Phillip Woode, a man Danielle just met on her latest job on a game show and her sex partner for the evening, and the murderess being Danielle’s twin sister, Dominique Blanchion, who is possessive of her sister. Emil helped Danielle cover up the murder. Grace, with the help of a private investigator named Joseph Larch, tries to find out what is going on, including where the dead body is, which Grace believes they could not have moved out of the apartment between the time she saw the murder and when she and the police initially arrived on the scene. If Grace and Larch find out the truth, they will learn of an unusual relationship between Danielle, Dominique and Emil, one with strong psychological overtones based on the scar Danielle has on her right hip. And even if Grace and/or Larch discover the truth, they may not survive what Emil in particular is willing to hide at any cost to protect Danielle.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

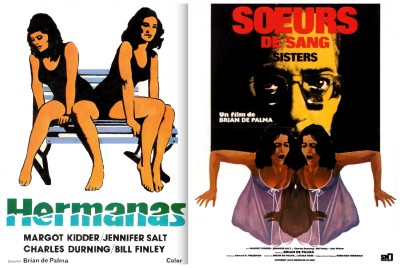

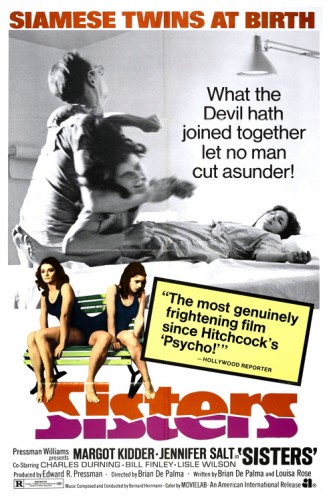

In a career spanning over four decades, filmmaker Brian De Palma is probably best known for his crime thrillers, directing successful and popular movies such as Carrie (1976), Dressed To Kill (1980), Scarface (1983), The Untouchables (1987), Carlito’s Way (1993), and Mission Impossible (1996), as well as being credited with fostering the careers of actors such as Robert De Niro, Jill Clayburgh, John C. Reilly, John Leguizamo, Andy Garcia and Margot Kidder. De Palma is without question a strange beast. His best notices tend to come from his large-scale studio pictures where, as a hired gun, his excesses could be tempered by a fleet of studio executives or a star whose vanity wouldn’t allow them to look to foolish. Hence The Untouchables and Mission Impossible – notably neither scripted by De Palma – contain all his trademark visual flamboyance and less of his rampant silliness inherent in his smaller, more personal Hitchcockian wannabes (though in terms of silliness, the explosive chewing-gum tunnel finale of Mission Impossible is hard to beat).

However his stylish, often hysterically overwrought (and generally just plain crazy) forays into Hitchcock territory can be immense fun with enough alcohol in the system. Sadly, some of his his later efforts – Raising Cain (1992) and Snake Eyes (1998) in particular – have shown the limitations of his relentless Hitchcock obsession. But, to his credit, the guy has stuck to his guns. An obvious cinephile, De Palma regularly pays homage in his films to the work of great directors of a previous generation – especially Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks – and for this reason his talent has been dismissed by some as purely derivative. Yet his most Hitchcockian film, Sisters (1973), remains his most original. It was also his first major work.

However his stylish, often hysterically overwrought (and generally just plain crazy) forays into Hitchcock territory can be immense fun with enough alcohol in the system. Sadly, some of his his later efforts – Raising Cain (1992) and Snake Eyes (1998) in particular – have shown the limitations of his relentless Hitchcock obsession. But, to his credit, the guy has stuck to his guns. An obvious cinephile, De Palma regularly pays homage in his films to the work of great directors of a previous generation – especially Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks – and for this reason his talent has been dismissed by some as purely derivative. Yet his most Hitchcockian film, Sisters (1973), remains his most original. It was also his first major work.

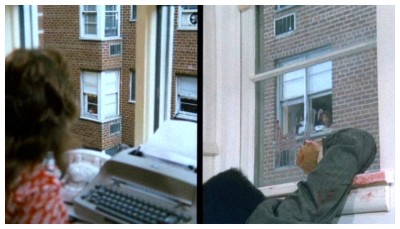

Sisters is a brilliantly structured thriller with strong fantasy elements, a story of voyeurism that opens with a Candid Camera-style television game show called Peeping Toms, in which a young man (Lisle Wilson) is embarrassed to see a young woman (apparently blind) undressing in front of him. The young man later takes home the actress who played the role, Danielle (Margot Kidder), and makes love to her. The following morning he is shockingly murdered by her jealous ‘sister’ but the murder is witnessed by a journalist named Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt) who lives across the courtyard – recalling Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). She calls in the police but, since there’s no body, the police don’t believe her.

Sisters is a brilliantly structured thriller with strong fantasy elements, a story of voyeurism that opens with a Candid Camera-style television game show called Peeping Toms, in which a young man (Lisle Wilson) is embarrassed to see a young woman (apparently blind) undressing in front of him. The young man later takes home the actress who played the role, Danielle (Margot Kidder), and makes love to her. The following morning he is shockingly murdered by her jealous ‘sister’ but the murder is witnessed by a journalist named Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt) who lives across the courtyard – recalling Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). She calls in the police but, since there’s no body, the police don’t believe her.

Grace continues to investigate on her own, even hiring a private detective (Charles Durning). She discovers that Danielle had a twin named Dominique, but is shocked to learn that Dominique died on the operating table when Doctor Emil Breton (William Finley), Danielle’s ex-husband, separated them. When the strange doctor takes Danielle to his private sanitarium, Grace follows, not realising she’ll end up becoming one of the patients. The ensuing events are too complex for synopsis here, and they are told in such a bravura manner with a particularly clever use being made of split-screen and point-of-view techniques.

Grace continues to investigate on her own, even hiring a private detective (Charles Durning). She discovers that Danielle had a twin named Dominique, but is shocked to learn that Dominique died on the operating table when Doctor Emil Breton (William Finley), Danielle’s ex-husband, separated them. When the strange doctor takes Danielle to his private sanitarium, Grace follows, not realising she’ll end up becoming one of the patients. The ensuing events are too complex for synopsis here, and they are told in such a bravura manner with a particularly clever use being made of split-screen and point-of-view techniques.

Danielle is a schizophrenic, and her dead sister Dominique lives on within her. If that’s all it was, we would have a clever sting-in-the-tail thriller of the moderately conventional kind. The real brilliance of Sisters is in the way journalist Grace is drawn closer and closer to this psychodrama, eventually becoming the twin sister herself during a hallucinatory flashback sequence. It is a tremendously well-wrought metaphor, whose implications go even further than anything Hitchcock managed in Vertigo (1958) or Psycho (1960), the other two films to which Sisters constantly alludes, right down to the use of a swirling musical score by Hitchcock’s old composer Bernard Herrmann. It is not necessarily a better film than either of these, but it is nevertheless extremely daring.

Danielle is a schizophrenic, and her dead sister Dominique lives on within her. If that’s all it was, we would have a clever sting-in-the-tail thriller of the moderately conventional kind. The real brilliance of Sisters is in the way journalist Grace is drawn closer and closer to this psychodrama, eventually becoming the twin sister herself during a hallucinatory flashback sequence. It is a tremendously well-wrought metaphor, whose implications go even further than anything Hitchcock managed in Vertigo (1958) or Psycho (1960), the other two films to which Sisters constantly alludes, right down to the use of a swirling musical score by Hitchcock’s old composer Bernard Herrmann. It is not necessarily a better film than either of these, but it is nevertheless extremely daring.

All the women in the film are oppressed by social and psychological pressures put upon them, and it is this that creates the Siamese sisterhood between a homicidal schizophrenic and the unhappy so-called ‘liberated’ journalist. This is a case where horror/fantasy cliches (nightmares of staring freaks, intimations of monstrousness) are used to make a point that resonates well beyond the horror genre, and says something important about real life. Indeed, by concentrating on the abnormal, the film throws the whole question of normalcy open. As to the morality of using real freaks in movies, students of such ethical questions could do worse than to compare Sisters with another seventies film, Michael Winner‘s The Sentinel (1976). The Sentinel, where the freaks are used to symbolise a world of monstrous evil, is pure sadistic exploitation of the worst kind. Sisters, however, is arguably acceptable. Again, the freaks stand for the ‘abnormal’ but this time in a context where the film’s ‘normal’ heroine is being brought face-to-face with her own abnormality.

All the women in the film are oppressed by social and psychological pressures put upon them, and it is this that creates the Siamese sisterhood between a homicidal schizophrenic and the unhappy so-called ‘liberated’ journalist. This is a case where horror/fantasy cliches (nightmares of staring freaks, intimations of monstrousness) are used to make a point that resonates well beyond the horror genre, and says something important about real life. Indeed, by concentrating on the abnormal, the film throws the whole question of normalcy open. As to the morality of using real freaks in movies, students of such ethical questions could do worse than to compare Sisters with another seventies film, Michael Winner‘s The Sentinel (1976). The Sentinel, where the freaks are used to symbolise a world of monstrous evil, is pure sadistic exploitation of the worst kind. Sisters, however, is arguably acceptable. Again, the freaks stand for the ‘abnormal’ but this time in a context where the film’s ‘normal’ heroine is being brought face-to-face with her own abnormality.

With a budget of only US$500,000 Sisters easily made its money back earning more than a million dollars on its initial release, and was met with critical praise. The late great Roger Ebert said the film was made more or less consciously as an homage to Hitchcock, adding that it nevertheless had a life of its own, and praised the performances of both Margot Kidder and Jennifer Salt. Vincent Canby of The New York Times: “A good substantial horror film. De Palma reveals himself here to be a first-rate director of more or less conventional material.” Variety: “A good psychological murder melodrama. Brian De Palma’s direction emphasises exploitation values which do not fully mask script weakness.” Sisters is rather violent for the year it was made in, but if it has one major problem, it’s that the opening sequence is so technically exciting, witty and suspenseful that it’s never equaled. This sequence also takes up so much screen time that the end comes much earlier than expected, long before we’ve been given a sufficient number of suspense sequences.

With a budget of only US$500,000 Sisters easily made its money back earning more than a million dollars on its initial release, and was met with critical praise. The late great Roger Ebert said the film was made more or less consciously as an homage to Hitchcock, adding that it nevertheless had a life of its own, and praised the performances of both Margot Kidder and Jennifer Salt. Vincent Canby of The New York Times: “A good substantial horror film. De Palma reveals himself here to be a first-rate director of more or less conventional material.” Variety: “A good psychological murder melodrama. Brian De Palma’s direction emphasises exploitation values which do not fully mask script weakness.” Sisters is rather violent for the year it was made in, but if it has one major problem, it’s that the opening sequence is so technically exciting, witty and suspenseful that it’s never equaled. This sequence also takes up so much screen time that the end comes much earlier than expected, long before we’ve been given a sufficient number of suspense sequences.

Given the ambiguous nature of Brian De Palma‘s relationship with genre films, it is difficult to predict where he will go next, but it would be surprising if he went on to become a truly creative auteur within the genre – his approach is far too manipulative. To refer to Roger Ebert again: “De Palma deserves more honour as a director. Consider also these titles: Sisters (1973), Blow Out (1981), The Fury (1978), Dressed To Kill (1981), Carrie (1976), Scarface (1983), Wise Guys (1986), Casualties Of War (1989), Carlito’s Way (1993), Mission Impossible (1996). Yes, there are a few failures along the way – Snake Eyes (1998), Mission To Mars (2000), The Bonfire Of The Vanities (1990) – but look at the range here, and reflect that these movies contain treasure for those who admire the craft as well as the story, who sense the glee with which De Palma manipulates images and characters for the simple joy of being good at it. It’s not just that he sometimes works in the style of Hitchcock, but that he has the nerve to.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the back side of Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Given the ambiguous nature of Brian De Palma‘s relationship with genre films, it is difficult to predict where he will go next, but it would be surprising if he went on to become a truly creative auteur within the genre – his approach is far too manipulative. To refer to Roger Ebert again: “De Palma deserves more honour as a director. Consider also these titles: Sisters (1973), Blow Out (1981), The Fury (1978), Dressed To Kill (1981), Carrie (1976), Scarface (1983), Wise Guys (1986), Casualties Of War (1989), Carlito’s Way (1993), Mission Impossible (1996). Yes, there are a few failures along the way – Snake Eyes (1998), Mission To Mars (2000), The Bonfire Of The Vanities (1990) – but look at the range here, and reflect that these movies contain treasure for those who admire the craft as well as the story, who sense the glee with which De Palma manipulates images and characters for the simple joy of being good at it. It’s not just that he sometimes works in the style of Hitchcock, but that he has the nerve to.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the back side of Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews