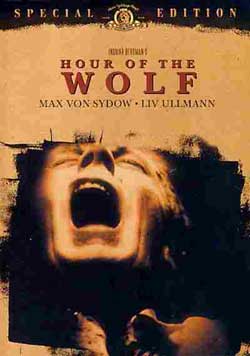

While vacationing on a remote Scandanavian island with his younger pregnant wife, an artist has a emotional breakdown while confronting his repressed desires.

REVIEW:

“Now you are yourself, but not yourself; an ideal state for a meeting between lovers.”

Often touted as Ingmar Bergman’s only “horror” film, Hour of the Wolf actually doesn’t stray from Bergman’s characteristic themes of madness, creative isolation, and paranoia. Explained in the film’s tagline, “The hour of the wolf is the hour between night and dawn. It is the hour when most people die, when sleep is deepest, when nightmares are most real. It is the hour when the sleepless are haunted by their deepest fear, when ghosts and demons are most powerful. It is also the hour when most children are born.” And so the audience must decipher whether these fears and demons are physical or psychological.

The protagonist is a painter named Johan Borg (Max von Sydow) who lives on the island, Baltrum (in Germany), with his wife, Alma (Liv Ullmann). When asleep he suffers from nightmares, when awake he is given to bouts of paranoia. There is an unspecified scandal in his past, yet his ability is highly regarded by the few inhabitants of the island. The film begins with Alma speaking to the audience directly; she gives her account of the story, of the disappearance of her husband, and of the strange circumstances surrounding it all. We then move to a series of flashbacks.

Johan says to Alma, “I call myself an artist for lack of a better name. In my creative work is nothing implicit except compulsion. Through no fault of mine I’ve been pointed out as something extraordinary, a calf with five legs, a monster.” Alma meets a spectral woman who advises her to read her husband’s memoirs. She does so and her psyche begins to merge with his psychosis. On the opposite of the island is Baron von Merkens (Erland Josephson) who lives in a castle and often entertains a queer assortment of guests. It isn’t long before Johan and Alma are invited to a party at the castle …

Like Bergman’s own Persona, the fourth wall is broken during the opening credit sequence. And like this disillusionment, Johan’s own dreams are suggested to be memories … some of them, or all of them, or none of them. It is his obsession over the reality of these images which causes him to feel that he is losing his mind and soon, Alma becomes frightened of him and what he might do out of desperation. These dreams/memories/fears are manifested by flickering bits of celluloid: of a man who walks up a wall and onto the ceiling, of an old woman who tears off her face when she removes her hat, of Johan as a child being locked in a closet by his parents and told that a small man lived there who feasted on children’s toes, of himself as an adult fishing off a cliff where he is attacked by a small boy whom he proceeds to brain with a stone and toss into the sea. These could very well be repressed recollections, projections of a fever dream, or perhaps, vampirically-induced hallucinations to soften his mind.

Granted, it is one of Bergman’s lesser films but this does not diminish the fact that it is expertly executed and consistent with the director’s usual recurring themes. He is a filmmaker capable of attaining immensely powerful emotions by distancing the viewer with cold reality or stark atmospheres.

Here, it is often interesting to see how he dispels certain horror clichés, borrowing from the likes of Bram Stoker and Val Lewton, only to later subvert or distort them into something oddly moving or infinitely more grotesque. Most notably, throughout the film the audience is never shown Johan’s works despite them being presented and commented upon by the characters. Bergman repeatedly said that art is about depicting human humiliation (a necessary aspect of human existence) and so, this is the ultimate degradation for the artist: his work is seen by those he cannot even be certain exist, and if they do exist then their motives are clearly suspect. Even in Bergman’s lesser works he allowed truths to ring and never feared, like Johan, to project his own insecurities into the minds of his audience.

Rating: B

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews