When I asked Horror News readers and Facebook friends to tell me their favourite feature films by first-time directors, I received a fantastic response. The suggestions poured in and all kinds of weird and wonderful titles fronted up for selection. While I can’t deny the quality or appeal of some nominations – Play Misty For Me (1971) by Clint Eastwood, Schlock The Banana Monster (1972) by John Landis, The Addams Family (1991) by Barry Sonnenfeld, Frailty (2001) by Bill Paxton, Undead (2003) by Michael Spierig & Peter Spierig – I have a somewhat limited education, so I can only count up to fifteen. But what a list it is, celebrating some of the best and most original genre films in the history of cinema. Please read on and embrace some of the most delicious directorial debuts you’re ever likely to witness!

When I asked Horror News readers and Facebook friends to tell me their favourite feature films by first-time directors, I received a fantastic response. The suggestions poured in and all kinds of weird and wonderful titles fronted up for selection. While I can’t deny the quality or appeal of some nominations – Play Misty For Me (1971) by Clint Eastwood, Schlock The Banana Monster (1972) by John Landis, The Addams Family (1991) by Barry Sonnenfeld, Frailty (2001) by Bill Paxton, Undead (2003) by Michael Spierig & Peter Spierig – I have a somewhat limited education, so I can only count up to fifteen. But what a list it is, celebrating some of the best and most original genre films in the history of cinema. Please read on and embrace some of the most delicious directorial debuts you’re ever likely to witness!

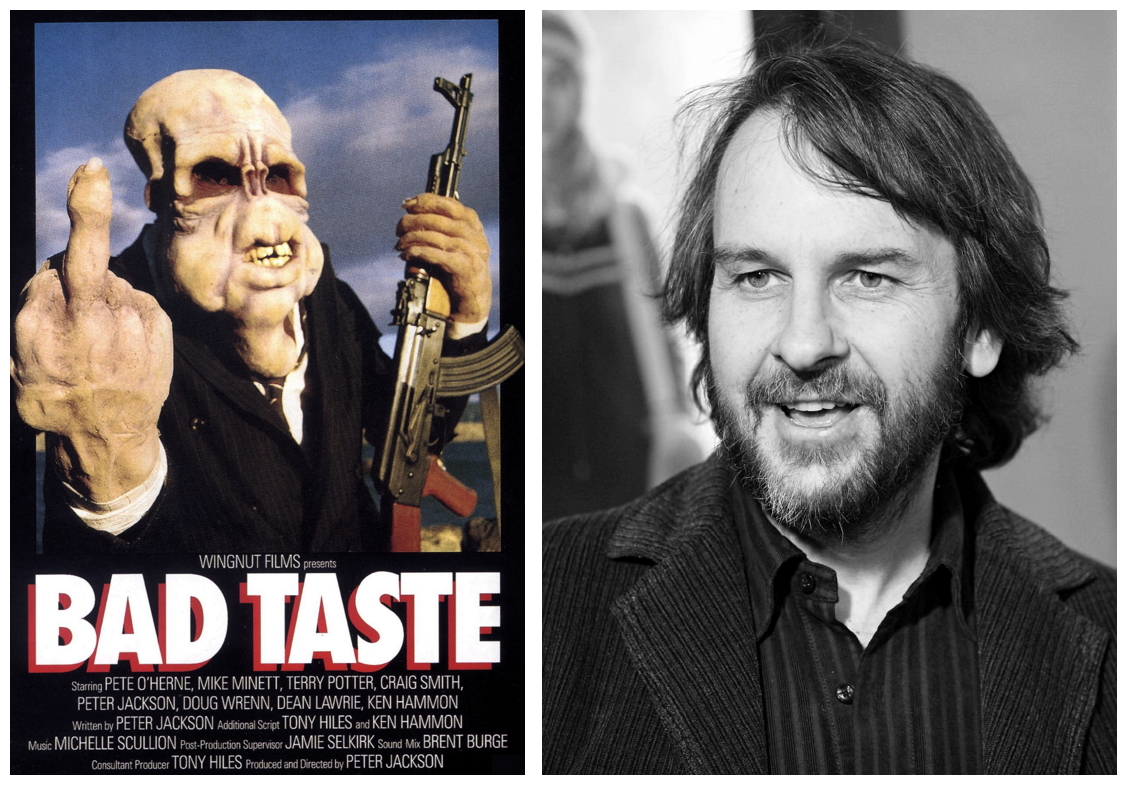

1. BAD TASTE (1987) From the man who brought you thousands of Uruk-Hai rampaging across the majestic plains of New Zealand, from the man who put a giant ape back on the Empire State Building where he belongs, and from the man who gave a hippo a machine gun, comes Peter Jackson‘s first feature film, which truly lives up to its title. It also demonstrates that all you need to make a movie is some film equipment, your friends and family, and about 180 free weekends. Of all the cast, only Peter Veer-Jones (as Lord Crumbe) worked outside of a Peter Jackson film, in such classic New Zealand television shows as Shortland Street, Hercules The Legendary Journeys and Xena Warrior Princess. Some of the cast appeared in Jackson’s second film Meet The Feebles (1989) – commonly referred to as Muppets On Ice – and had worked on later Jackson films. If making Bad Taste has taught Jackson anything, it was you can get away with a lame story and no real actors, as long as you can smear special effects over the top, thus ensuring his inevitable Hollywood career.

1. BAD TASTE (1987) From the man who brought you thousands of Uruk-Hai rampaging across the majestic plains of New Zealand, from the man who put a giant ape back on the Empire State Building where he belongs, and from the man who gave a hippo a machine gun, comes Peter Jackson‘s first feature film, which truly lives up to its title. It also demonstrates that all you need to make a movie is some film equipment, your friends and family, and about 180 free weekends. Of all the cast, only Peter Veer-Jones (as Lord Crumbe) worked outside of a Peter Jackson film, in such classic New Zealand television shows as Shortland Street, Hercules The Legendary Journeys and Xena Warrior Princess. Some of the cast appeared in Jackson’s second film Meet The Feebles (1989) – commonly referred to as Muppets On Ice – and had worked on later Jackson films. If making Bad Taste has taught Jackson anything, it was you can get away with a lame story and no real actors, as long as you can smear special effects over the top, thus ensuring his inevitable Hollywood career.

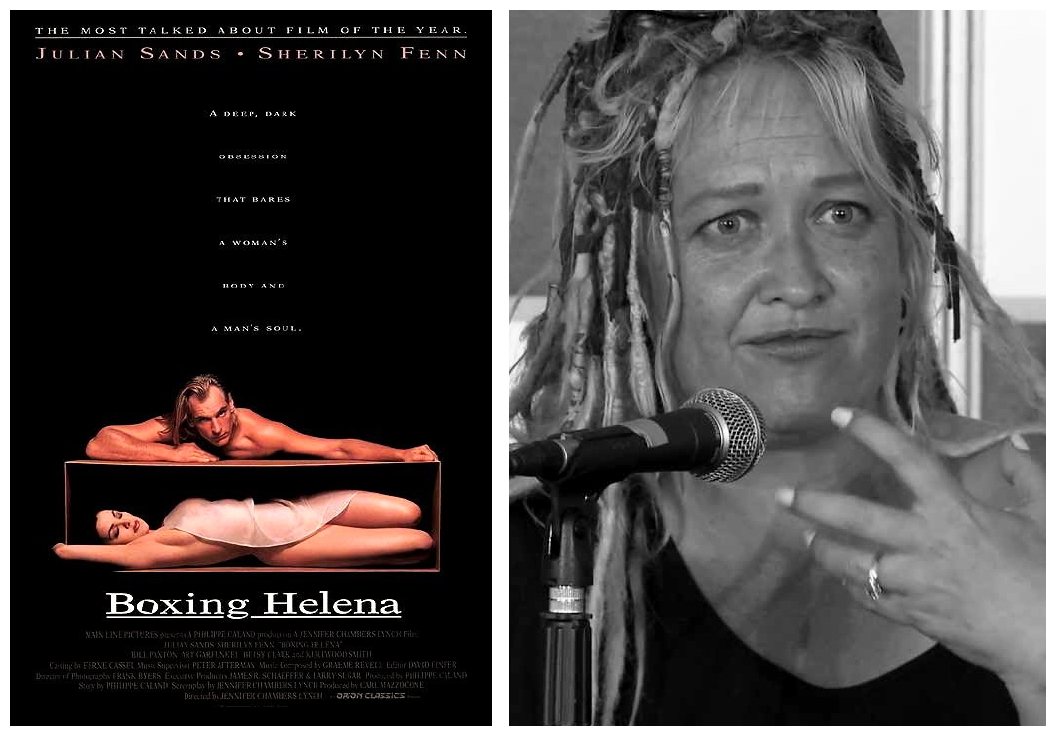

2. BOXING HELENA (1993) The first feature to be directed by Jennifer Lynch, daughter of auteur David Lynch, may start out looking like a remake of The Brain That Wouldn’t Die (1958), but Boxing Helena succeeds in pushing the boundaries between love and sadism and art and entertainment. Nick (Julian Sands) is a brilliant surgeon who appears to have everything a man could desire. He’s rich, successful, obsessed with his mother and a rather poor dresser – check out his jogging suit! But beneath his seemingly perfect life is a secret burning desire. Nick is obsessed with Helena (Sherilyn Fenn), a young beautiful temptress with whom he once shared an unforgettable night with. When Helena is tricked into visiting Nick and gets run over by a Chevy Nova, Nick comes up with a brilliant plan to save her life and win her love – he cuts off her legs. Nick cares for Helena by drugging her and keeping her prisoner. Slowly but surely he tries to win her heart but Helena still resists his romantic advances, so Nick devises another brilliant plan – he cuts off her arms. Lovely Sherilyn Fenn played the difficult role of Helena, and Jennifer Lynch retreated from the public eye for many years but returned to the spotlight with the films Surveillance (2008) and Hisss aka Nagin (2010).

2. BOXING HELENA (1993) The first feature to be directed by Jennifer Lynch, daughter of auteur David Lynch, may start out looking like a remake of The Brain That Wouldn’t Die (1958), but Boxing Helena succeeds in pushing the boundaries between love and sadism and art and entertainment. Nick (Julian Sands) is a brilliant surgeon who appears to have everything a man could desire. He’s rich, successful, obsessed with his mother and a rather poor dresser – check out his jogging suit! But beneath his seemingly perfect life is a secret burning desire. Nick is obsessed with Helena (Sherilyn Fenn), a young beautiful temptress with whom he once shared an unforgettable night with. When Helena is tricked into visiting Nick and gets run over by a Chevy Nova, Nick comes up with a brilliant plan to save her life and win her love – he cuts off her legs. Nick cares for Helena by drugging her and keeping her prisoner. Slowly but surely he tries to win her heart but Helena still resists his romantic advances, so Nick devises another brilliant plan – he cuts off her arms. Lovely Sherilyn Fenn played the difficult role of Helena, and Jennifer Lynch retreated from the public eye for many years but returned to the spotlight with the films Surveillance (2008) and Hisss aka Nagin (2010).

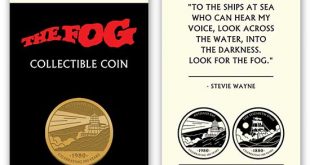

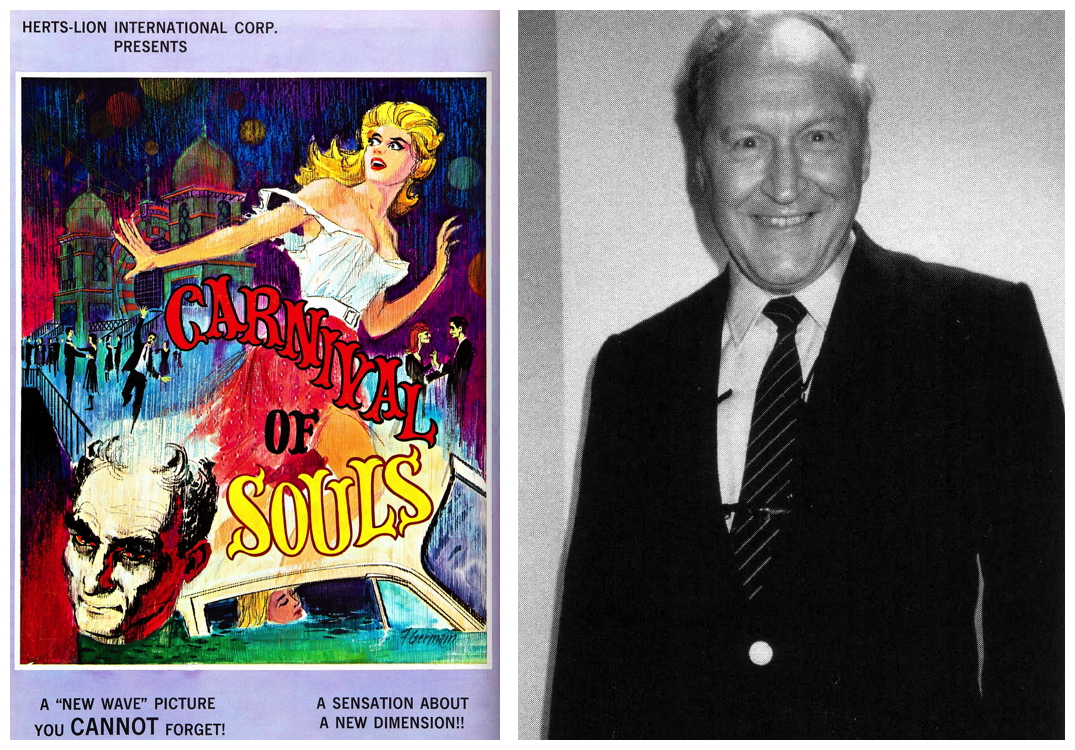

3. CARNIVAL OF SOULS (1962) If you look up ‘Sleeper’ or ‘Cult’ in any good movie dictionary, you’ll find this chiller that many film fans often mention as one of their own personal discoveries, and an inspiration to generations of low-budget film-makers. This creepy cult horror stars Candace Hillgoss, an actress imported from New York, so she already feels alienated. She plays Mary, the lone survivor of the car crash we see in the prologue. Mary has accepted a job as church organist. Where ever she goes, she sees a death-like figure who seems to be pursuing her. She also finds herself being strangely drawn to a deserted dark carnival. The director and lead ghoul Herk Harvey never made another film, making it even more of a cult item. Carnival Of Souls has a lot of clever creepy scenes, like when Mary can’t hear anything, silent and invisible to the people around her, getting on a bus only to find it full of ghouls, the Dance Of The Dead and, of course, the finale. Harvey had such a bad experience with distribution on Carnival Of Souls that he never made another film, and never made any money from it until its restored video release a quarter of a century later. In the interim, Carnival Of Souls would not let him rest. Even in the chopped versions that screened on late-night television or the pirated versions that circulated on video, the horror movie became a cult classic.

3. CARNIVAL OF SOULS (1962) If you look up ‘Sleeper’ or ‘Cult’ in any good movie dictionary, you’ll find this chiller that many film fans often mention as one of their own personal discoveries, and an inspiration to generations of low-budget film-makers. This creepy cult horror stars Candace Hillgoss, an actress imported from New York, so she already feels alienated. She plays Mary, the lone survivor of the car crash we see in the prologue. Mary has accepted a job as church organist. Where ever she goes, she sees a death-like figure who seems to be pursuing her. She also finds herself being strangely drawn to a deserted dark carnival. The director and lead ghoul Herk Harvey never made another film, making it even more of a cult item. Carnival Of Souls has a lot of clever creepy scenes, like when Mary can’t hear anything, silent and invisible to the people around her, getting on a bus only to find it full of ghouls, the Dance Of The Dead and, of course, the finale. Harvey had such a bad experience with distribution on Carnival Of Souls that he never made another film, and never made any money from it until its restored video release a quarter of a century later. In the interim, Carnival Of Souls would not let him rest. Even in the chopped versions that screened on late-night television or the pirated versions that circulated on video, the horror movie became a cult classic.

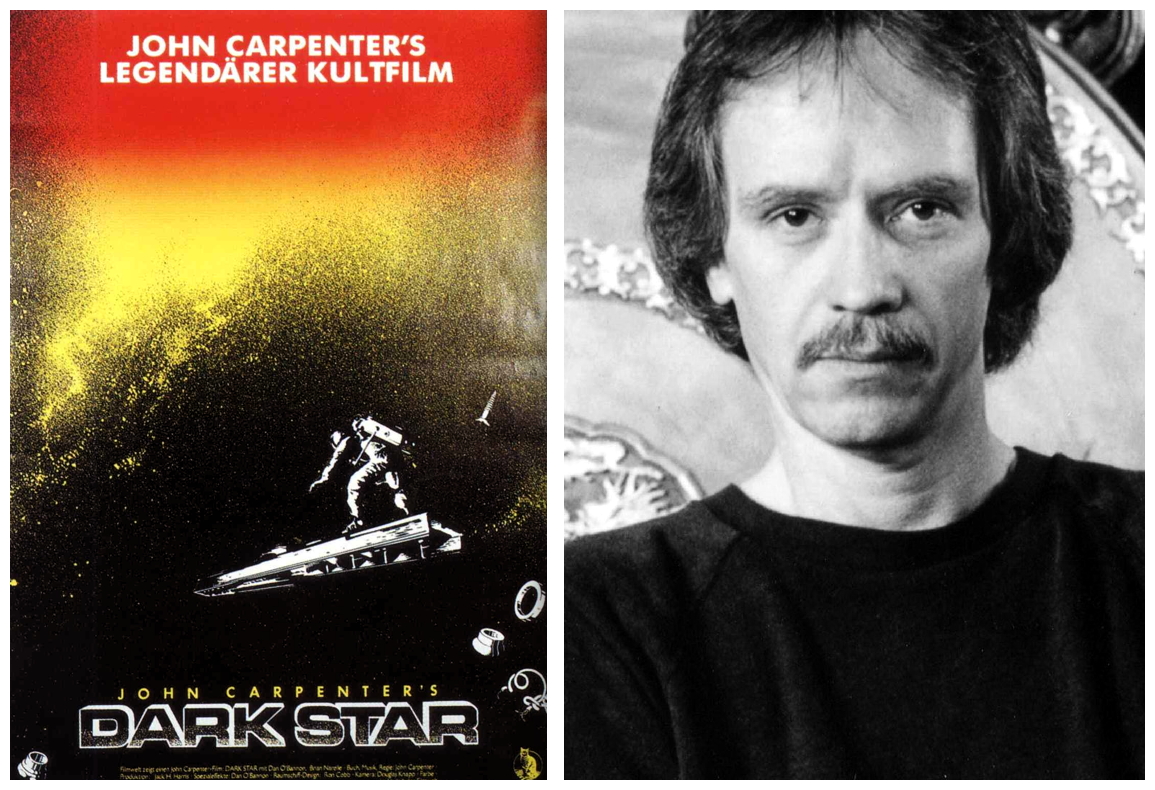

4. DARK STAR (1974) John Carpenter was one of the new generation of young directors to come out of the same film school, the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. Though his first feature Dark Star was well received at film festivals, it was years before it gained any sort of wide distribution, and he didn’t become generally known to the film-going public until the release of Halloween (1978). Dark Star was originally a 45-minute short film shot on 16mm for around US$6,000, the brainchild of Carpenter and co-writer/co-director/co-star Dan O’Bannon and, for the next three years, they spent all their spare time working on the film, financing it out of their own pockets. Jack H. Harris, producer of low-budget genre films, provided the necessary money to enable extra footage to be shot by O’Bannon and to transfer the whole film onto 35mm, bringing the total budget to US$60,000. The result is a splendidly inventive, hip, irreverent space satire that provocatively illustrates how astronauts, when confined to their spaceship for too long, become irretrievably ‘spaced-out’. This dehumanisation theme is much better realised here than in Carpenter’s version of The Thing (1982) and O’Bannon would later write Alien (1979), Dead And Buried (1981), Blue Thunder (1983), The Return Of The Living Dead (1985), Lifeforce (1985), Invaders From Mars (1986), Total Recall (1990) and Screamers (1995). One of the highlights is a long sequence in which the witless Sergeant Pinback tries to feed the alien they’ve taken on board. Although the scene is pure comedy, you’ll recognise it as the genesis of Alien.

4. DARK STAR (1974) John Carpenter was one of the new generation of young directors to come out of the same film school, the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. Though his first feature Dark Star was well received at film festivals, it was years before it gained any sort of wide distribution, and he didn’t become generally known to the film-going public until the release of Halloween (1978). Dark Star was originally a 45-minute short film shot on 16mm for around US$6,000, the brainchild of Carpenter and co-writer/co-director/co-star Dan O’Bannon and, for the next three years, they spent all their spare time working on the film, financing it out of their own pockets. Jack H. Harris, producer of low-budget genre films, provided the necessary money to enable extra footage to be shot by O’Bannon and to transfer the whole film onto 35mm, bringing the total budget to US$60,000. The result is a splendidly inventive, hip, irreverent space satire that provocatively illustrates how astronauts, when confined to their spaceship for too long, become irretrievably ‘spaced-out’. This dehumanisation theme is much better realised here than in Carpenter’s version of The Thing (1982) and O’Bannon would later write Alien (1979), Dead And Buried (1981), Blue Thunder (1983), The Return Of The Living Dead (1985), Lifeforce (1985), Invaders From Mars (1986), Total Recall (1990) and Screamers (1995). One of the highlights is a long sequence in which the witless Sergeant Pinback tries to feed the alien they’ve taken on board. Although the scene is pure comedy, you’ll recognise it as the genesis of Alien.

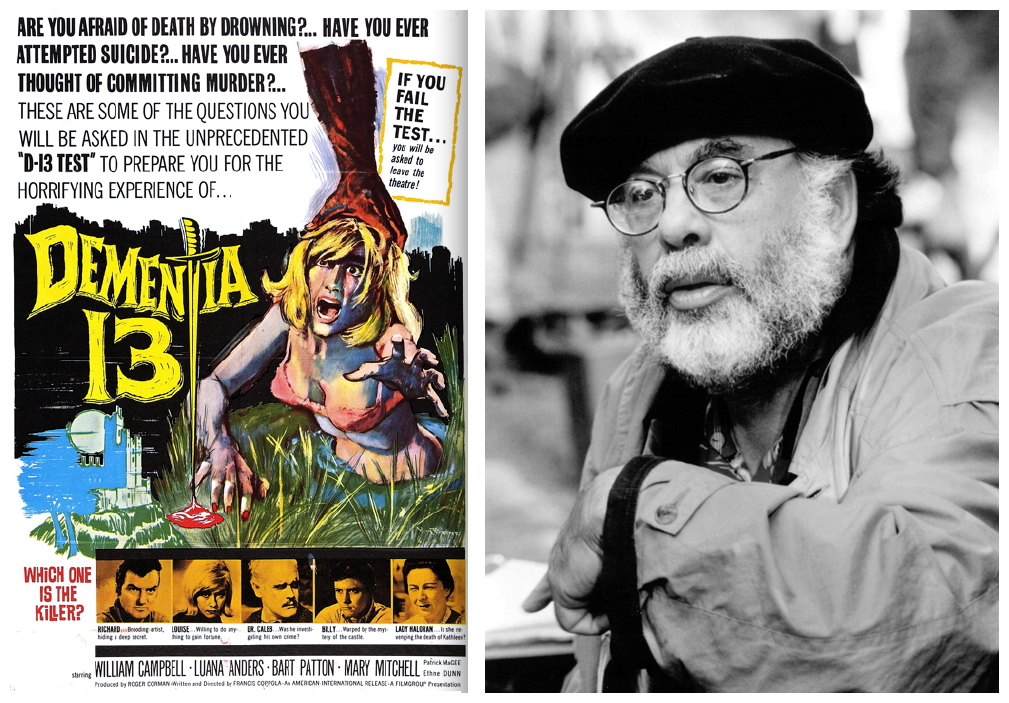

5. DEMENTIA 13 (1963) This is the first official film of Francis Ford Coppola who won Oscars for both The Godfather (1972) and Godfather Part II (1974). Before this he directed two soft-core p**n films, The Bellboy And The Showgirls (1962) and Tonight For Sure (1962). He leaves both of those off his CV. He also directed one-fifth of The Terror (1963), along with Roger Corman, Monte Hellman, Jack Hill, and a struggling young actor by the name of Jack Nicholson. As with any emerging film trend, Corman was right there at the ground level, in fact you could say he was on the basement level with A Bucket Of Blood (1959). So when Coppola came to him and said, “I could take the second unit of The Young Racers (1963) and shoot a cheap Psycho (1960) knock-off in that mansion over there,” he was using two words dear to Corman’s heart: ‘cheap’ and ‘knock-off’. Dementia 13 basically has two things going for it, and her name is Luana Anders. She was a popular character actress at the time, but was even better known as one of Jack Nicholson’s professional girlfriends, scoring appearances in such Nicholson films as Easy Rider (1969) and Goin’ South (1978).

5. DEMENTIA 13 (1963) This is the first official film of Francis Ford Coppola who won Oscars for both The Godfather (1972) and Godfather Part II (1974). Before this he directed two soft-core p**n films, The Bellboy And The Showgirls (1962) and Tonight For Sure (1962). He leaves both of those off his CV. He also directed one-fifth of The Terror (1963), along with Roger Corman, Monte Hellman, Jack Hill, and a struggling young actor by the name of Jack Nicholson. As with any emerging film trend, Corman was right there at the ground level, in fact you could say he was on the basement level with A Bucket Of Blood (1959). So when Coppola came to him and said, “I could take the second unit of The Young Racers (1963) and shoot a cheap Psycho (1960) knock-off in that mansion over there,” he was using two words dear to Corman’s heart: ‘cheap’ and ‘knock-off’. Dementia 13 basically has two things going for it, and her name is Luana Anders. She was a popular character actress at the time, but was even better known as one of Jack Nicholson’s professional girlfriends, scoring appearances in such Nicholson films as Easy Rider (1969) and Goin’ South (1978).

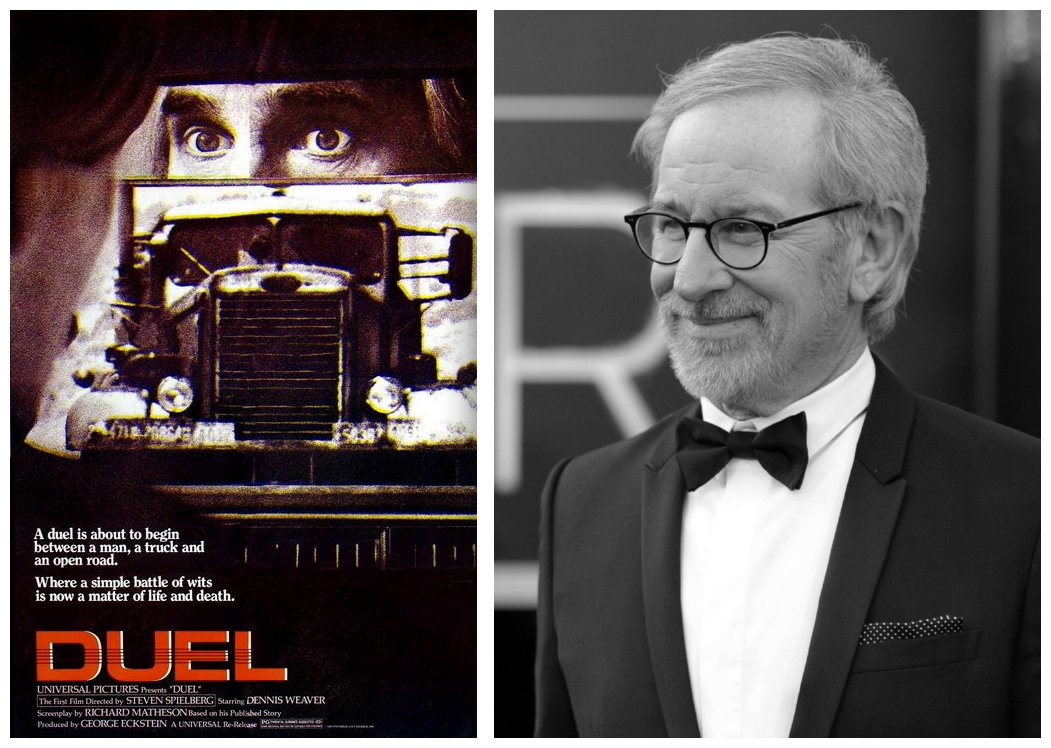

6. DUEL (1971) Steven Spielberg‘s name came to public notice in a modest way with his first feature which was made for American television and broadcast in November 1971. It wasn’t his first professional work, however. He had tried to enter the film school at the University of Southern California on the basis of some amateur movies he had made. He failed. They accepted George Lucas, John Milius and John Carpenter, but they would not take young Spielberg. Eventually, at the age of 21, after haunting the lot at Universal Studios, he was given a job as one of three directors making a television pilot for a new series called Night Gallery. Duel is a text-book example of the Monster Movie – one of the best ever made – with a very unusual monster, a large rather decrepit-looking semi-trailer truck. Dennis Weaver plays the man in Duel whose car is repeatedly attacked for no particular reason by a truck he has overtaken. It’s definitely the truck that is the ‘monster’ and not its driver, who is never fully seen. The film has virtually no dialogue, it is pure cinema brilliantly edited, about an ordinary man-in-the-street (like most of Spielberg’s heroes), being driven to the brink of madness by a violent attack out of no-where. The idea of horror erupting out of normality is basic to the Monster Movie, and it has rarely been done better. The script was by the Richard Matheson, based on his own short story originally published in Playboy magazine.

6. DUEL (1971) Steven Spielberg‘s name came to public notice in a modest way with his first feature which was made for American television and broadcast in November 1971. It wasn’t his first professional work, however. He had tried to enter the film school at the University of Southern California on the basis of some amateur movies he had made. He failed. They accepted George Lucas, John Milius and John Carpenter, but they would not take young Spielberg. Eventually, at the age of 21, after haunting the lot at Universal Studios, he was given a job as one of three directors making a television pilot for a new series called Night Gallery. Duel is a text-book example of the Monster Movie – one of the best ever made – with a very unusual monster, a large rather decrepit-looking semi-trailer truck. Dennis Weaver plays the man in Duel whose car is repeatedly attacked for no particular reason by a truck he has overtaken. It’s definitely the truck that is the ‘monster’ and not its driver, who is never fully seen. The film has virtually no dialogue, it is pure cinema brilliantly edited, about an ordinary man-in-the-street (like most of Spielberg’s heroes), being driven to the brink of madness by a violent attack out of no-where. The idea of horror erupting out of normality is basic to the Monster Movie, and it has rarely been done better. The script was by the Richard Matheson, based on his own short story originally published in Playboy magazine.

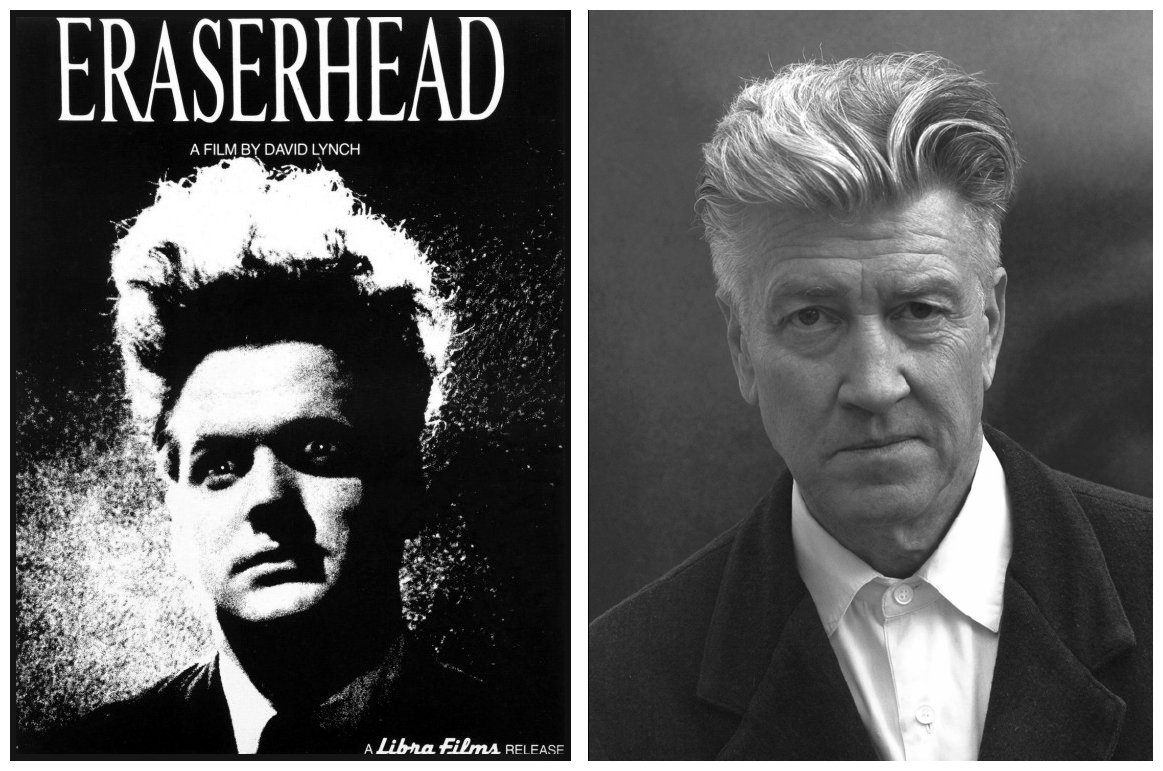

7. ERASERHEAD (1977) The tradition of surrealism has always been alive at the low-budget end of the market. Then again, low budget films are often the work of auteurs, people who can pretty much do what they like without a committee of financiers looking gloomily over their shoulders. Such filmmakers are often young, hungry and ambitious, and their films may reflect the slightly desperate vigour such a state induces. The most extraordinary of these cheap surrealist fantasies is David Lynch‘s Eraserhead. It tells the story of Henry (played with a wild-haired staring autistic quality by John Nance), who is inadequate, bluntly polite, withdrawn and almost entirely incapable of ordinary social contact. He lives in a squalid one-room apartment, and has a marginal relationship with a skinny hysterical girl named Mary (Charlotte Stewart) whose family – human rejects living in an urban wasteland – alternate between total passivity and violent mania that borders on epilepsy. Eraserhead is the ultimate student film, the ultimate experimental film, and the last word in personal film-making. This unique film has marvelous special effects, stop-motion animation, crisp black-and-white photography and fantastic scenic design. Furthermore, it has startling moments of horror, sex and brilliant black comedy.

7. ERASERHEAD (1977) The tradition of surrealism has always been alive at the low-budget end of the market. Then again, low budget films are often the work of auteurs, people who can pretty much do what they like without a committee of financiers looking gloomily over their shoulders. Such filmmakers are often young, hungry and ambitious, and their films may reflect the slightly desperate vigour such a state induces. The most extraordinary of these cheap surrealist fantasies is David Lynch‘s Eraserhead. It tells the story of Henry (played with a wild-haired staring autistic quality by John Nance), who is inadequate, bluntly polite, withdrawn and almost entirely incapable of ordinary social contact. He lives in a squalid one-room apartment, and has a marginal relationship with a skinny hysterical girl named Mary (Charlotte Stewart) whose family – human rejects living in an urban wasteland – alternate between total passivity and violent mania that borders on epilepsy. Eraserhead is the ultimate student film, the ultimate experimental film, and the last word in personal film-making. This unique film has marvelous special effects, stop-motion animation, crisp black-and-white photography and fantastic scenic design. Furthermore, it has startling moments of horror, sex and brilliant black comedy.

8. THE EVIL DEAD (1981) Sam Raimi dropped out of college to set up Renaissance Productions with high school friends Robert Tapert and Bruce Campbell. “I was in college studying literature and history and, of course, forestalling a career trying to make as many movies as I could. I was expecting to drag out my college years and then take a real job doing something else. And then Rob said, ‘Why don’t we make a feature film, since we seem to be doing it in Super-8?’ Finally, we got evicted because we were playing our Super-8 movies too loud. It was either find another apartment or go into the movie business.” The three amigos made a thirty-minute Super-8 version of The Evil Dead called Within The Woods to show to potential backers. “We’d make people sick then ask them to invest.” They made them sick enough to part with US$430,000, and Saturday the 11th November 1979, cast and crew headed for the hills. Raimi’s inventive camerawork made The Evil Dead stand out from the horror crowd: “We couldn’t afford a Steadicam, so we improvised. We mounted the camera in the middle of a two-by-four about fifteen feet long. A couple of guys grabbed it, one on either end, and they just ran like hell.” The Evil Dead almost didn’t get released, as every major distributor passed on Raimi’s gore-fest. Raimi had just about given up hope when author Stephen King saw the film and published a glowing review: “What Raimi achieves in The Evil Dead is a black rainbow of horror,” praising the simple story, effective makeup and exhilarating cinematography, saying of Raimi’s fluid camera work, “Somebody ought to tell Kubrick, Spielberg, et al, that there’s really nothing to this stuff. Just bolt the camera to a two-by-four and run like hell.”

8. THE EVIL DEAD (1981) Sam Raimi dropped out of college to set up Renaissance Productions with high school friends Robert Tapert and Bruce Campbell. “I was in college studying literature and history and, of course, forestalling a career trying to make as many movies as I could. I was expecting to drag out my college years and then take a real job doing something else. And then Rob said, ‘Why don’t we make a feature film, since we seem to be doing it in Super-8?’ Finally, we got evicted because we were playing our Super-8 movies too loud. It was either find another apartment or go into the movie business.” The three amigos made a thirty-minute Super-8 version of The Evil Dead called Within The Woods to show to potential backers. “We’d make people sick then ask them to invest.” They made them sick enough to part with US$430,000, and Saturday the 11th November 1979, cast and crew headed for the hills. Raimi’s inventive camerawork made The Evil Dead stand out from the horror crowd: “We couldn’t afford a Steadicam, so we improvised. We mounted the camera in the middle of a two-by-four about fifteen feet long. A couple of guys grabbed it, one on either end, and they just ran like hell.” The Evil Dead almost didn’t get released, as every major distributor passed on Raimi’s gore-fest. Raimi had just about given up hope when author Stephen King saw the film and published a glowing review: “What Raimi achieves in The Evil Dead is a black rainbow of horror,” praising the simple story, effective makeup and exhilarating cinematography, saying of Raimi’s fluid camera work, “Somebody ought to tell Kubrick, Spielberg, et al, that there’s really nothing to this stuff. Just bolt the camera to a two-by-four and run like hell.”

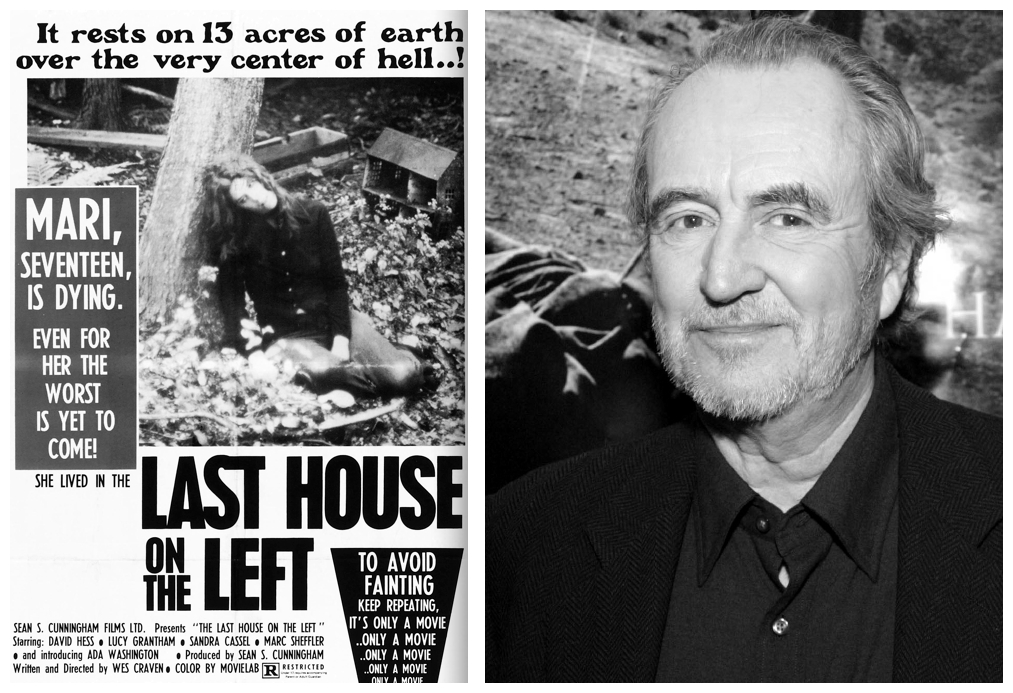

9. THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT (1972) A master of schlock horror and shock tactics, Wes Craven has moved from the periphery to the commercial mainstream in tandem with society’s changing tastes and widening standards of acceptance. The Last House On The Left, while not being his first success, was at least characteristic in its concentration on the gruesome and the grotesque, of what was to come. Commercial heaven (in the guise of Hollywood money-men) came to Craven in recognition of his infinitely respectable thrills in A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984) and Craven has doggedly followed the same scenarios and the same ghoul-strewn path ever since, most recently with his enormously successful Scream (1996) franchise. Craven’s directorial debut broke new ground in realistic gore movies and is still shocking, primarily because it doesn’t have the audience-winking humour his later films developed. This low-budget unstoryboarded movie includes rape, torture, humiliation, nudity, stabbings, disembowelment, castration, chainsaw murders – and that’s just the stuff Craven left in! Teenager Mari Collingwood (Sandra Peabody) is late coming home for her birthday party, and that’s because she and a female friend, while trying to score some marijuana for a night of fun, are kidnapped, raped and tortured by escaped convicts. Although Craven and producer Sean Cunningham were deliberately going for shock value, former humanities teacher Craven said that even he was appalled by some of the material in the their fly-by-night project.

9. THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT (1972) A master of schlock horror and shock tactics, Wes Craven has moved from the periphery to the commercial mainstream in tandem with society’s changing tastes and widening standards of acceptance. The Last House On The Left, while not being his first success, was at least characteristic in its concentration on the gruesome and the grotesque, of what was to come. Commercial heaven (in the guise of Hollywood money-men) came to Craven in recognition of his infinitely respectable thrills in A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984) and Craven has doggedly followed the same scenarios and the same ghoul-strewn path ever since, most recently with his enormously successful Scream (1996) franchise. Craven’s directorial debut broke new ground in realistic gore movies and is still shocking, primarily because it doesn’t have the audience-winking humour his later films developed. This low-budget unstoryboarded movie includes rape, torture, humiliation, nudity, stabbings, disembowelment, castration, chainsaw murders – and that’s just the stuff Craven left in! Teenager Mari Collingwood (Sandra Peabody) is late coming home for her birthday party, and that’s because she and a female friend, while trying to score some marijuana for a night of fun, are kidnapped, raped and tortured by escaped convicts. Although Craven and producer Sean Cunningham were deliberately going for shock value, former humanities teacher Craven said that even he was appalled by some of the material in the their fly-by-night project.

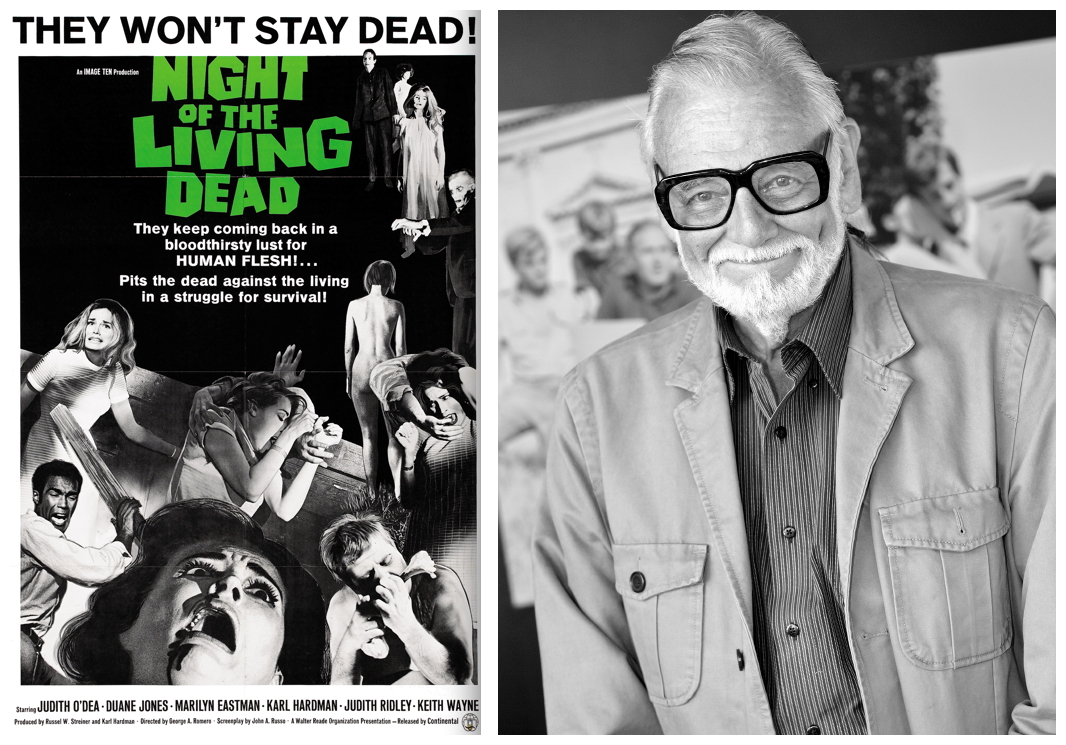

10. NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) Like a lot of great horror films, including Carnival Of Souls (1962), Night Of The Living Dead was the first feature by a director of industrial films, but unlike Carnival Of Souls, it wasn’t the last one. George Romero, fresh from the intense graphic horror of Night Of The Living Dead, went on to make such comedies as There’s Always Vanilla (1971) and Hungry Wives (1972), and they did so well that it’s probably the first time you’ve ever heard of them. So yes, he did go back to horror with The Crazies (1973), the quasi-vampire film Martin (1977), Monkey Shines (1988), The Dark Half (1993) and Bruiser (2000). What he’s really known for is the sequels to Night Of The Living Dead: Dawn Of The Dead (1978), Day Of The Dead (1985), Land Of The Dead (2005) and Diary Of The Dead (2007). Night Of The Living Dead was originally written by Romero and John Russo as a horror comedy called Monster Flick which, at the time, was about alien invaders who befriend a group of teenagers and could possibly be mistaken for Teenagers From Outer Space (1959), so they returned to the writing board and added the living dead which Romero called ‘ghouls’ after the television executives he had as clients.

10. NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) Like a lot of great horror films, including Carnival Of Souls (1962), Night Of The Living Dead was the first feature by a director of industrial films, but unlike Carnival Of Souls, it wasn’t the last one. George Romero, fresh from the intense graphic horror of Night Of The Living Dead, went on to make such comedies as There’s Always Vanilla (1971) and Hungry Wives (1972), and they did so well that it’s probably the first time you’ve ever heard of them. So yes, he did go back to horror with The Crazies (1973), the quasi-vampire film Martin (1977), Monkey Shines (1988), The Dark Half (1993) and Bruiser (2000). What he’s really known for is the sequels to Night Of The Living Dead: Dawn Of The Dead (1978), Day Of The Dead (1985), Land Of The Dead (2005) and Diary Of The Dead (2007). Night Of The Living Dead was originally written by Romero and John Russo as a horror comedy called Monster Flick which, at the time, was about alien invaders who befriend a group of teenagers and could possibly be mistaken for Teenagers From Outer Space (1959), so they returned to the writing board and added the living dead which Romero called ‘ghouls’ after the television executives he had as clients.

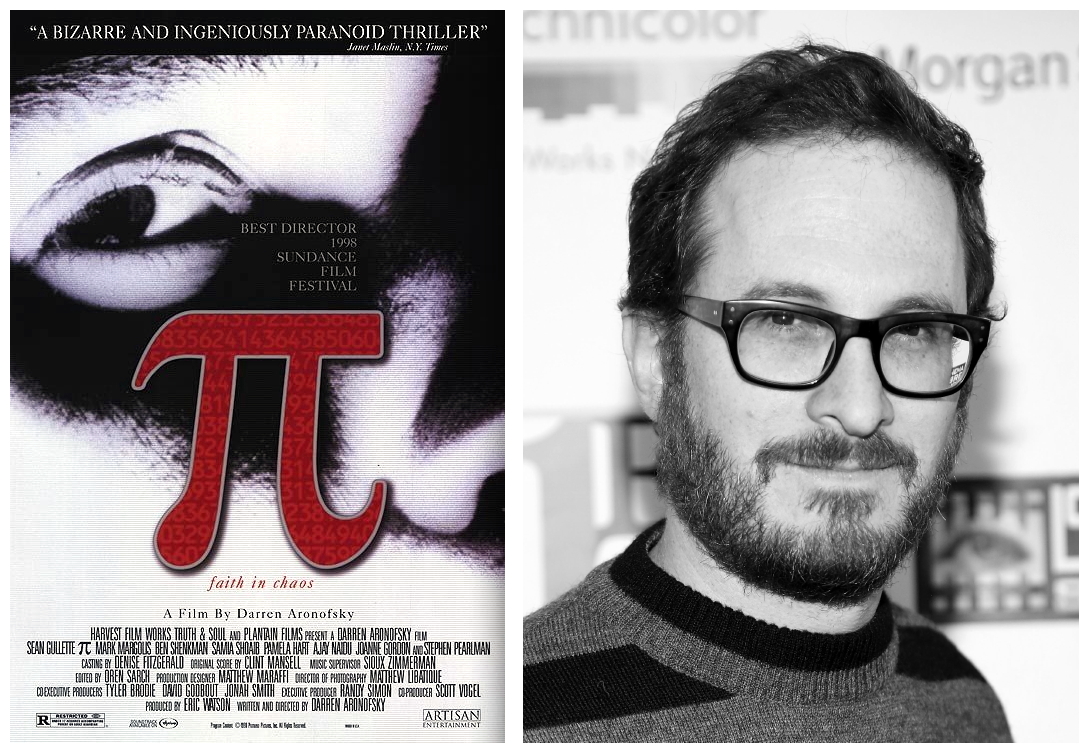

11. PI (1998) The ‘Faith In Chaos’ tag-line on the poster gives a definite flavour of the contradictions and conflicts depicted in this number-crunching-meets-end-of-the-millenium movie, and efficiently conveys the core themes of number theory and religion while simultaneously suggesting a sense of mystery. The chaos is all focused on the struggles of mathematician Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) as he looks for patterns in the random numbers of the stock exchange while failing to communicate with the people around him: his mentor Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), Lenny the Hasidic Jew studying the Torah (Ben Shenkman), his neighbours, and the persistent corporate suits who want to employ him. Pi is rightly acclaimed as a masterpiece of subjective cinema. The story Max relates about looking directly into the sun when he was a child also hint most strongly this is a failure of vision. Pi is a film with a single narrative point of view – Max’s – everything and all the viewer sees is what he experiences. Director Darren Aronofsky uses a range of cinematic effects to enhance this association with Max’s state of mind. When Max walks the streets, Aronofsky employs a camera attached to the actor, commonly referred to as a Snorricam. This separates Max from his environment, depicting his isolation and alienation. The subtle changes in film speed strangely disorient the viewer.

11. PI (1998) The ‘Faith In Chaos’ tag-line on the poster gives a definite flavour of the contradictions and conflicts depicted in this number-crunching-meets-end-of-the-millenium movie, and efficiently conveys the core themes of number theory and religion while simultaneously suggesting a sense of mystery. The chaos is all focused on the struggles of mathematician Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) as he looks for patterns in the random numbers of the stock exchange while failing to communicate with the people around him: his mentor Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), Lenny the Hasidic Jew studying the Torah (Ben Shenkman), his neighbours, and the persistent corporate suits who want to employ him. Pi is rightly acclaimed as a masterpiece of subjective cinema. The story Max relates about looking directly into the sun when he was a child also hint most strongly this is a failure of vision. Pi is a film with a single narrative point of view – Max’s – everything and all the viewer sees is what he experiences. Director Darren Aronofsky uses a range of cinematic effects to enhance this association with Max’s state of mind. When Max walks the streets, Aronofsky employs a camera attached to the actor, commonly referred to as a Snorricam. This separates Max from his environment, depicting his isolation and alienation. The subtle changes in film speed strangely disorient the viewer.

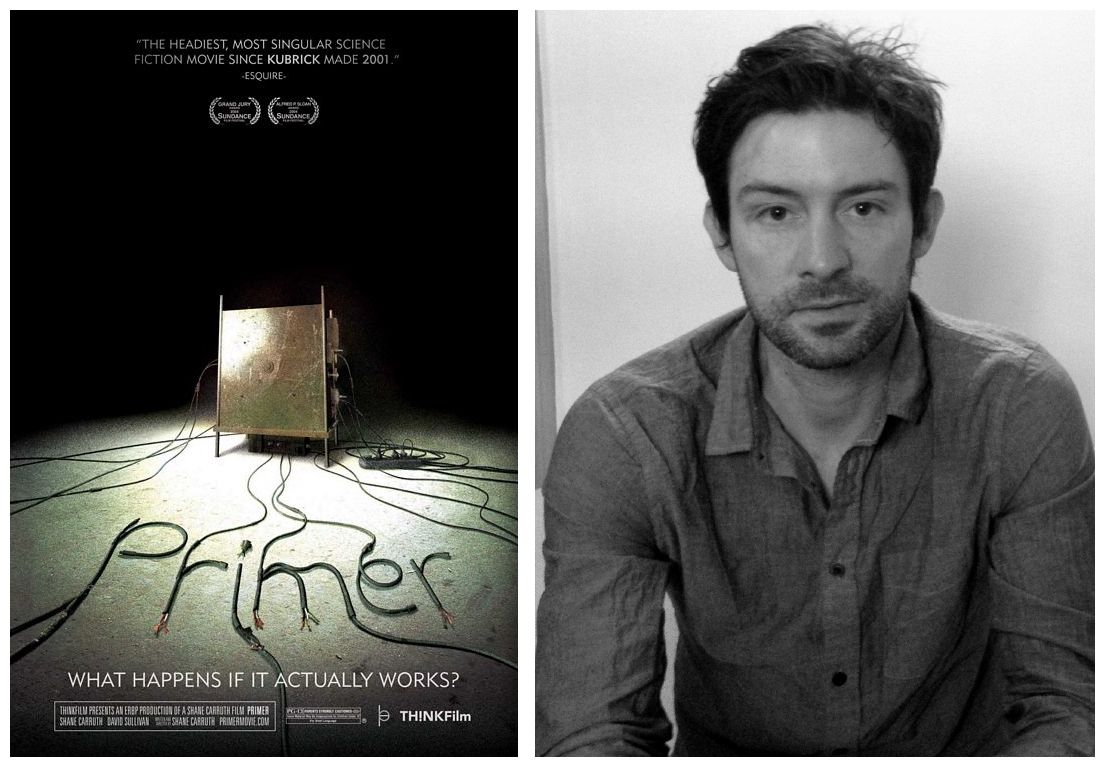

12. PRIMER (2004) The concept of time travel is depicted so thoroughly in Shane Carruth‘s debut feature film that it seems like we’re watching people trapped in a self-inflicted experiment. Carruth presents his unusual story in a manner not unlike like a dramatised documentary. The extremely low budget (US$7000 mostly spent on film stock) actually allows Carruth to focus on his characters and their interactions, backing everything with solid physics. There’s a fair amount of technobabble right from the start. Abe (David Sullivan) and Aaron (Carruth) are two ambitious engineers who turn out to be too smart for their own good. We are introduced to them in the middle of their everyday routine, inhabiting their own world and have their own habits and jargon. This might seem confusing to someone peeking in from the outside but, then again, this is the perfect way for the filmmaker to suck us into the story. While we’re trying to grasp what’s going on, we start to get familiar with those characters and, when the time-travel aspect finally kicks in, you’ll be tempted to rewind back to some earlier scenes, because the devil certainly is in the detail. Before becoming a filmmaker, Carruth was a university math major who developed flight simulation software, and it shows. He not only wrote, directed and produced, he also composed the music and performed one of the two central roles (he was forced to cast himself as Aaron after having trouble finding actors who wouldn’t fill each line with so much drama) and the rest of the cast is mostly made up by either friends or family members.

12. PRIMER (2004) The concept of time travel is depicted so thoroughly in Shane Carruth‘s debut feature film that it seems like we’re watching people trapped in a self-inflicted experiment. Carruth presents his unusual story in a manner not unlike like a dramatised documentary. The extremely low budget (US$7000 mostly spent on film stock) actually allows Carruth to focus on his characters and their interactions, backing everything with solid physics. There’s a fair amount of technobabble right from the start. Abe (David Sullivan) and Aaron (Carruth) are two ambitious engineers who turn out to be too smart for their own good. We are introduced to them in the middle of their everyday routine, inhabiting their own world and have their own habits and jargon. This might seem confusing to someone peeking in from the outside but, then again, this is the perfect way for the filmmaker to suck us into the story. While we’re trying to grasp what’s going on, we start to get familiar with those characters and, when the time-travel aspect finally kicks in, you’ll be tempted to rewind back to some earlier scenes, because the devil certainly is in the detail. Before becoming a filmmaker, Carruth was a university math major who developed flight simulation software, and it shows. He not only wrote, directed and produced, he also composed the music and performed one of the two central roles (he was forced to cast himself as Aaron after having trouble finding actors who wouldn’t fill each line with so much drama) and the rest of the cast is mostly made up by either friends or family members.

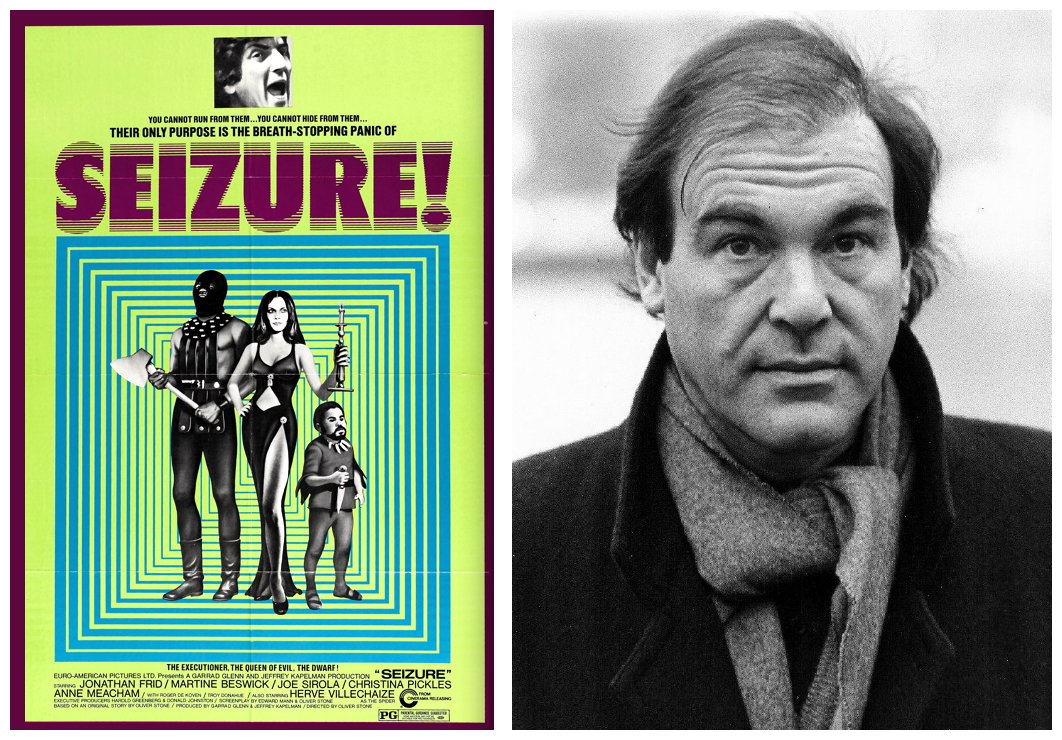

13. SEIZURE (1974) Screenwriting alone could not contain Oliver Stone‘s creative impulses back in 1973 so, after co-writing a script with Edward Mann, Ollie decided to direct. Seizure, also known in various countries as Queen Of Evil or Tango Macabre, concerns horror author Edmund Blackstone (Jonathan Frid) who is plagued by nightmares. He and his wife (Christina Pickles) invite a number of guests to their isolated country house for a relaxing weekend but, after a few go missing, they are confronted with three villainous characters from Edmund’s imagination, the physical manifestations of his nightmares: The provocative and sultry Queen Of Evil (Martine Beswick), the giant strongman Jackal (Henry Judd Baker) and a dwarf assassin named Spider (Hervé Villechaize). Stone’s little-seen directorial debut was made in Quebec: “You have to stretch to like it. It wasn’t great. I felt back then the same as I do now, that I always wanted to direct, and the horror genre was easier to break in with.” As schlocky as Seizure is, it still shows a certain style that can charitably be called seminal Stone. Its archetypes of evil would show up later in a more subtle form – Tom Berenger as the amoral lieutenant in Platoon (1986), Michael Douglas as the unscrupulous trader of Wall Street (1987), the murderous Mickey in Natural Born Killers (1994).

13. SEIZURE (1974) Screenwriting alone could not contain Oliver Stone‘s creative impulses back in 1973 so, after co-writing a script with Edward Mann, Ollie decided to direct. Seizure, also known in various countries as Queen Of Evil or Tango Macabre, concerns horror author Edmund Blackstone (Jonathan Frid) who is plagued by nightmares. He and his wife (Christina Pickles) invite a number of guests to their isolated country house for a relaxing weekend but, after a few go missing, they are confronted with three villainous characters from Edmund’s imagination, the physical manifestations of his nightmares: The provocative and sultry Queen Of Evil (Martine Beswick), the giant strongman Jackal (Henry Judd Baker) and a dwarf assassin named Spider (Hervé Villechaize). Stone’s little-seen directorial debut was made in Quebec: “You have to stretch to like it. It wasn’t great. I felt back then the same as I do now, that I always wanted to direct, and the horror genre was easier to break in with.” As schlocky as Seizure is, it still shows a certain style that can charitably be called seminal Stone. Its archetypes of evil would show up later in a more subtle form – Tom Berenger as the amoral lieutenant in Platoon (1986), Michael Douglas as the unscrupulous trader of Wall Street (1987), the murderous Mickey in Natural Born Killers (1994).

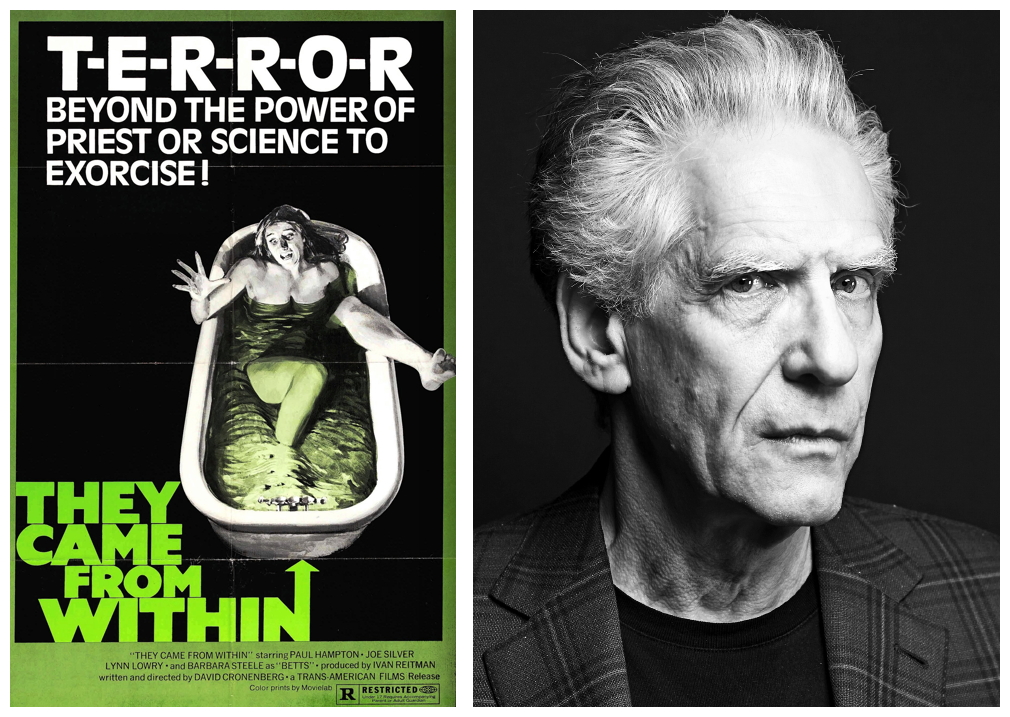

14. SHIVERS (1975) Most of David Cronenberg‘s films prey on the frailty of the human body and the deviousness of the human mind, and contain metaphors for society’s twisted perception of social mores and human nature. In The Fly (1986), Jeff Goldblum‘s humanity gives way to his baser nature as a fly’s genetic makeup gradually overtakes his body and, in Dead Ringers (1988), Jeremy Irons plays twin gynecologists who are attached psychologically until death do them part. Eastern Promises (2007) features a graphically violent fight scene in a steam bath where the combatants wield razor-sharp linoleum cutters, while A History Of Violence (2005) is a conscious homage to Sam Peckinpah films. Videodrome (1983) is a brilliant satire on media dominance in our culture and, in Naked Lunch (1991), Peter Weller suffers writer’s block so badly that he imagines his typewriter as a gooey imperious insect. All these films can trace their ancestry back to Shivers, also known in various countries and languages as They Came From Within, The Parasite Murders or Orgy Of The Blood Parasites. Starring Joe Silver, Paul Hampton and veteran scream queen Barbara Steele, and produced by a young Ivan Reitman, Shivers is a deeply black comedy set in an upper middle-class apartment building. What the film gives us, on a small scale, is sexual apocalypse directed with lunatic conviction, and a series of rather revolting variations on the theme of parasitic infection. Soon the apartment building resembles one of the less enlightened levels of Dante’s Inferno, and the film ends as the building’s occupants climb into their cars with manic gaiety and drive out to infect the rest of Canada, then the world.

14. SHIVERS (1975) Most of David Cronenberg‘s films prey on the frailty of the human body and the deviousness of the human mind, and contain metaphors for society’s twisted perception of social mores and human nature. In The Fly (1986), Jeff Goldblum‘s humanity gives way to his baser nature as a fly’s genetic makeup gradually overtakes his body and, in Dead Ringers (1988), Jeremy Irons plays twin gynecologists who are attached psychologically until death do them part. Eastern Promises (2007) features a graphically violent fight scene in a steam bath where the combatants wield razor-sharp linoleum cutters, while A History Of Violence (2005) is a conscious homage to Sam Peckinpah films. Videodrome (1983) is a brilliant satire on media dominance in our culture and, in Naked Lunch (1991), Peter Weller suffers writer’s block so badly that he imagines his typewriter as a gooey imperious insect. All these films can trace their ancestry back to Shivers, also known in various countries and languages as They Came From Within, The Parasite Murders or Orgy Of The Blood Parasites. Starring Joe Silver, Paul Hampton and veteran scream queen Barbara Steele, and produced by a young Ivan Reitman, Shivers is a deeply black comedy set in an upper middle-class apartment building. What the film gives us, on a small scale, is sexual apocalypse directed with lunatic conviction, and a series of rather revolting variations on the theme of parasitic infection. Soon the apartment building resembles one of the less enlightened levels of Dante’s Inferno, and the film ends as the building’s occupants climb into their cars with manic gaiety and drive out to infect the rest of Canada, then the world.

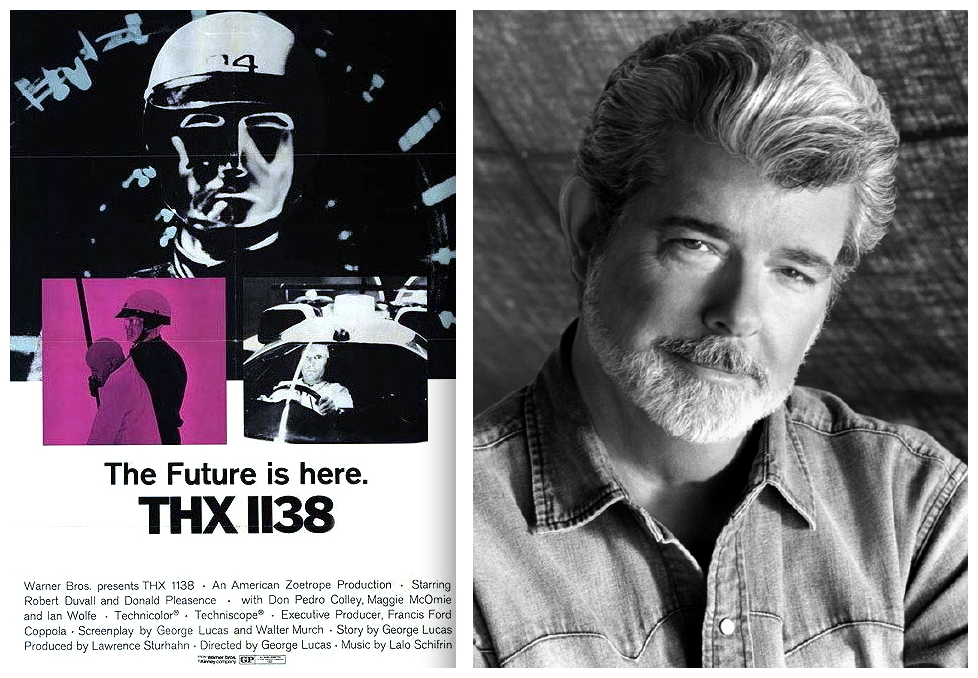

15. THX 1138 (1971) The plot will be familiar to any science fiction reader, set in a totalitarian subterranean society of the future run by computers in which bland human technocrats act as both supervisors of the machinery and supervisors of each other. Everyone is fed a constant supply of sedative drugs and any sign of individuality is forbidden. Everyone wears the same white clothing and all heads are shaved. This uniformity also helps blur the differences between the sexes – good thing too, as sexual intercourse is also forbidden, with all breeding done through cloning and artificial insemination. THX 1138 is an early work from filmmaker George Lucas, who has since earned a permanent place in the history of cinema with his creation of Star Wars IV A New Hope (1977) which, at the time, became the most successful film ever. George started work on THX 1138 when he was still at the University of Southern California film school, making a fifteen-minute short film called THX 1138:4EB (1967) which subsequently won a number of awards. He then won a scholarship to observe the making of Finian’s Rainbow (1968) which was being directed by Francis Ford Coppola, another young filmmaker only a few years older than George. Coppola had somehow persuaded Warner Brothers to allow him to set-up his own production company called American Zoetrope, with which he proposed to produce high-quality low-budget features. One of these was THX 1138 but, despite some positive reviews, it did so badly at the box-office that Coppola was faced with financial ruin until the success of The Godfather (1972) saved the day for him.

15. THX 1138 (1971) The plot will be familiar to any science fiction reader, set in a totalitarian subterranean society of the future run by computers in which bland human technocrats act as both supervisors of the machinery and supervisors of each other. Everyone is fed a constant supply of sedative drugs and any sign of individuality is forbidden. Everyone wears the same white clothing and all heads are shaved. This uniformity also helps blur the differences between the sexes – good thing too, as sexual intercourse is also forbidden, with all breeding done through cloning and artificial insemination. THX 1138 is an early work from filmmaker George Lucas, who has since earned a permanent place in the history of cinema with his creation of Star Wars IV A New Hope (1977) which, at the time, became the most successful film ever. George started work on THX 1138 when he was still at the University of Southern California film school, making a fifteen-minute short film called THX 1138:4EB (1967) which subsequently won a number of awards. He then won a scholarship to observe the making of Finian’s Rainbow (1968) which was being directed by Francis Ford Coppola, another young filmmaker only a few years older than George. Coppola had somehow persuaded Warner Brothers to allow him to set-up his own production company called American Zoetrope, with which he proposed to produce high-quality low-budget features. One of these was THX 1138 but, despite some positive reviews, it did so badly at the box-office that Coppola was faced with financial ruin until the success of The Godfather (1972) saved the day for him.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews