SYNOPSIS:

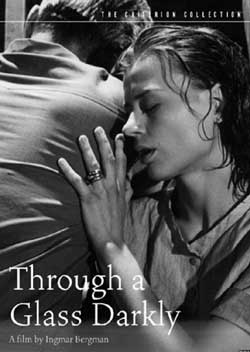

A young woman, Karin, has recently returned to the family island after spending some time in a mental hospital. On the island with her is her lonely brother and kind, but increasingly desperate husband (‘Max von Sydow’). They are joined by Karin’s father (‘Gunnar Björnstrand’), who is a world-traveling author that is estranged to his children. The film depicts how Karin’s grip on reality slowly slips away and how the bonds between the family members are changing in light of this fact.

REVIEW:

“Father spoke to me.”

From 1961 to 1963, Ingmar Bergman wrote and directed what has come to be christened his Silence of God trilogy. This was the first in the trilogy (to be followed by Winter Light, and then, The Silence). He described it as a three-act chamber film depicting twenty-four hours in the lives of a family of four on summer holiday. Three men affected by a woman, a catalyst, who exposes their most inherent faults. Through a Glass Darkly was also the first of Bergman’s films shot on his home island of Faro (some of the others being Persona, Shame, and Scenes from a Marriage). Like most of his films, it begins with vagaries and banalities, foreshadowing the abattoir of emotional conflict soon to come.

The family has emerged from a refreshing swim in the sea, discussing who will prepare dinner and catch tomorrow’s. Karin (Harriet Andersson) has recently been released from an asylum where she was being treated for a disease never named but similarly described as schizophrenia. Her husband and physician, Martin (Max von Sydow), tells her father, David (Gunnar Bjornstrand), that her condition is irremediable. Martin is genuinely concerned but feels helpless; he has no other hope than to make her remaining days of sanity as pleasant as possible. David is a highly-lauded novelist who has been suffering writer’s block. He has returned from a trip to Switzerland and intends to leave again in a month’s time. When he announces this to the others, they are wounded. He attempts to quell their disappointment with impromptu gifts, then leaves and weeps in private. He is guilty of observing life while excluding it; imprisoning himself in a personal cell of creativity. Minus (Lars Passgard) is Karin’s 17-year-old brother. He is starved for his father’s appreciation. He feels his father’s preoccupations have deprived them of ever having a genuine conversation. Minus senses Karin’s restlessness as well and this summons repressed sexual feelings within himself.

The three younger members devise a surprise for David; the gift of a play written by Minus. David is outwardly appreciative but internally interprets it as an assault on his personal integrity for it is an attack on the artifice of “ready-made” art. The awkwardness in this scene is palpable and played to great effect by the actors. That night, after shunning Martin’s amorous suggestions, Karin follows the sound of a foghorn to the attic where she hears voices behind a peeling section of wallpaper. The minimalism of this scene is cinematic perfection, the restraint in showing nothing uniquely visual yet exuding an unsettlingly pure provocative mood. Later, she spies her father’s memoirs and learns that her disease is incurable. She reads further that he has become obsessed with recording her psychological decline for use as material in a future novel.

Next morning, the older men are fishing. Martin accuses David of selfishness in his art and of neglecting Karin. David acquiesces that this may be true. He confesses attempting suicide in the past from the guilt of avoiding life for the sake of his compulsion to write. Karin tells Minus of the peeling wallpaper, that it was a door. She tells him that there were voices on the other side waiting for something. God was on the other side, she says, and he was a spider. Bergman is ambiguous as to whether Karin is suffering from religious hysteria or adjusting to her heightened reception of god’s intangible presence, the purity of her encounters lending credence to either conclusion.

A major theme in the film is how we project ourselves onto other things: people and objects, places and emotions. The power of obsession: these personal compulsions which deprive us of emotional interaction – all of it serving to exclude us one from another, victims of our own selfish endeavours. The intimacy of Bergman’s art is unparalleled for it reflects the pain of its creator in such an effortlessly naturalistic yet harrowing way. Bergman’s work is, perhaps, of the most self-indulgent sort but it always speaks to humanity’s greatest struggles. Bergman’s questions of the spiritual, the psychological, and the artistic are relevant to all of us (as Karin says in the film, “It is so horrible to see your own confusion and understand it.”). The film is also a prime representation of Bergman’s character portraits, as it was with Fanny and Alexander, Winter Light, Cries and Whispers, The Serpent’s Egg, and many others.

Bergman’s longtime collaborator, Sven Nykvist, was a master cinematographer capable of lighting scenes to great effect. By painting light on the faces of these characters, an aesthetic separation is created visually reflecting their emotional dynamic. Musically, there is only the dispersal of Bach’s Sarabande; that deep cello, progressive yet trudging, imploring yet ruined. Of all his works, Bergman’s trilogy cuts the deepest, for it is both the joyous search for faith and the empty-handed return home. “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

Rating: B+

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews