SYNOPSIS:

A group of three disenfranchised young men, Lung (Lung Tin Sang), Ko (Che Bin Law) and Paul (Albert Au) set off a bomb in a movie theatre. Fleeing from the scene of the crime, they run into the beautiful but dangerous Wan-chu (Lin Chen Chi), who spends her days torturing animals and arguing with her neighbours. Wan-chu threatens to turn the gang into the Police and blackmails them into committing ever increasingly brutal crimes which can only result in their own annihilation.

REVIEW:

Tsui Hark’s third film is a brutal and bloody affair which takes no prisoners – shocking scenes of animal cruelty (some of which are purportedly real), graphic images of torture plumbing the depths of human sadism, the brutality of which is continually punctuated by black humour, and an explosive finalé involving a Mexican standoff in a graveyard between the young men, the police and Americans Vietnam Veterans turned mercenaries depicts a Hong Kong in flux where criminality and corruption run riot. It is essential to remember that at this time Hong Kong was a colonial offshoot of the United Kingdom, previously having been occupied by Japan during the Second World War, and ceded back to Great Britain after Japan’s unconditional defeat in 1945. It is little surprise therefore that First Encounters of the Dangerous Kind portrays colonial imposters from the past and present in a negative light.

In the original theatrical version, Hark was forced to cut scenes of bombings (which are crucial to the film’s overall political critique) as authorities deemed such scenes too inflammatory at the time (as these were not only a direct reference to bombings by left wing groups that took place between 1966 and 1967 but also showed the young men making the bombs and potentially providing a DIY guide for other disenfranchised youths), and in their place insert additional scenes including the pivotal encounter between the young men and Wan-chu – in this version the encounter takes place after Wan-chu witnesses the men running over a tourist and therefore the implicit political critique of Hong Kong in the 1970s is removed – here it is meaningless violence towards the innocent that provides the origins of the narrative trauma. The Director’s cut which is reviewed here, seems incoherent in places, and it is difficult to discern whether this is because the version is not a proper restoration, or whether the uncut version was meant to be such.

While reviewers have compared Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind to Mario Bava’s Rabid Dogs (Italy: 1974) but it also bears a great deal of similarity to other ‘angry young men’ films of the 1960s and 1970s including Yuke Yuke Nidome no Shojo/Go, Go, Second Time Virgin (Kōji Wakamatsu, 1969) and The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, US: 1979). At the same time, many reviewers have noted the ‘borrowing’ of music from Western films, and in particular from Argento’s score for Romero’s Dawn of the Dead.

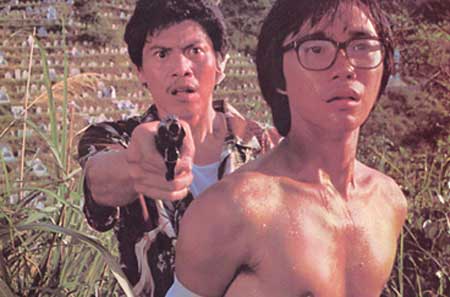

The anger here is against an urbanised and industrialised society in which young people find themselves outsiders, rendered voiceless and ultimately alienated. While the fact that Wan-chu’s home life is fractured as a result of the death of both parents, which means that she is being looked after by her older brother, a Police officer who is never at home, perhaps makes her desperation and violent actions understandable, the young men come from good families and their violence is a result of ennui rather than abandonment. Barbed wire fencing, onto which Wan-chu carelessly and cruelly throws the neighbour’s cat at the beginning of the film, and on whose torturous spikes Wan-chu meets her own death towards the film’s climax, is a powerful metaphor of urban alienation as entrapment within a growing industrialised nation. Like elsewhere in Asia, most notably in Japan and South Korea, economic prosperity was made possible over and because of the disposable bodies of the working classes.

Economic prosperity has human consequences, especially for those who are rendered powerless by the processes of rapid modernization. This is clear in Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind, in which corruption is widespread and tourists and ‘foreigners’ are seen as more powerful and profitable than local residents. A comedic episode where Wan-chu and her hapless helpers hijack a bus full of American tourists makes this political critique explicit: the use of humour here working to shield this political critique from the censors. Put together with the violent and vengeful American mercenaries, who hunt down the gang in order to retrieve a contract and banker’s drafts for Japanese yen that they steal from one of them, the anti-American sentiment clearly subverts the touristic image of a harmonious multi-cultural Hong Kong, which permeated dominant discourses of nationhood at the time and can be seen in contemporary nostalgic Hong Kong cinema.

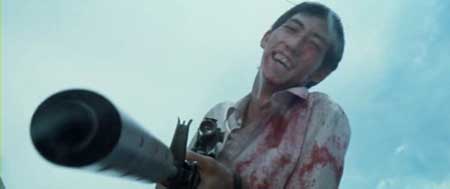

After the black humour of the attempted bombing of the hijacked tourist bus, the relationships between the group become fractured and Man-chu once more is abandoned, before being thrown off the balcony of her dilapidated apartment that she shares with her brother. Hunted by the mercenaries and the Police, the male gang’s only recourse is to more meaningless violence, which like a never ending cycle, just begets more violence, and can only end in utter destruction and death. The Mexican stand-off at the climax between the young men, the Americans and Detective Tan takes place at a cemetery (reminding me of a similar chase scene in Mario Bava’s seminal La ragazza che sapeva troppo/The Girl Who Knew Too Much, Italy: 1962), and is a fittingly violent finalé as the film ends as it began with an incendiary bang.

There is little doubt that Tsui Hark is one of Hong Kong cinema’s finest contemporary directors, and that Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind is not his finest film – or at least in my opinion. In its current form, it seems disjointed, some of the humour misplaced, and real cruelty towards animals for the pleasure of cinematic viewers, even to make a political point, can never be condoned. While there is some dispute over the death of the cat, there is general consensus that the scenes of cruelty towards mice are indeed real.

And while there seems to be a great deal of academic apologia for such scenes, this is not my view. As such, I find myself in a difficult position in recommending the film even though I acknowledge its merits in terms of Hong Kong’s ‘alternative’ cinematic history and the strong performance by Lin Chen Chi as the disposed and unsympathetic Wan-chu. A critique of violence should never involve acts of violence on those who either do not or cannot consent (whether animal or human), because in the process one repeats the cycle of violence rather than critiques it and as viewers, it makes us complicit with such acts of violence which have been perpetrated for our enjoyment. In the final analysis, Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind is a memorable film, but for me, for all the wrong reasons.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews