SYNOPSIS:

The world has been devastated by a virus that has decimated the adult population leaving small children and teenagers to roam the scarred landscape attempting to form some kind of society with dramatic and violent results

REVIEW:

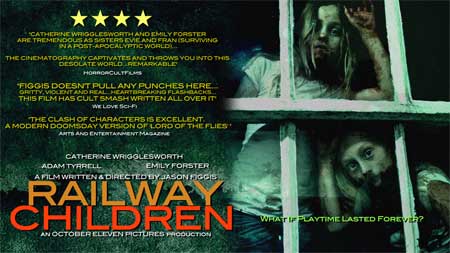

Artful horror is rarely ever uplifting material. Jim Mickle’s “We Are What We Are” and Jeremy Gardner’s “The Battery” were the two most beautifully rendered films I’ve had the pleasure of reviewing this past year, but both left me thankful there weren’t any prescription pills lying about. Factor in that writer/director Jason Figgis and his company October Eleven Pictures hail from Ireland, and I mentally prepared myself for his post-apocalyptic take on Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” to be anything but a walk in the park. Indeed, that proverbial stroll is one thing “Children of a Darker Dawn” is not.

Originally entitled “Railway Children” (from a novel by Edith Nesbit, which I have not read but sounds fairly depressing itself), “Dawn” plops us right into the midst of a ravaged Earth with no initial clue what the hell caused it. The only living survivors of a worldwide pandemic are human youths, forced to forage for canned goods and supplies while living in constant fear and suspicion of one another. This trash-strewn wasteland is witnessed through the eyes of adolescent Fran (Emily Forster) and her older teen sister Evie, played with ferocious conviction by Catherine Wrigglesworth.

As they traverse the countryside surrounding Dublin presumably months after the outbreak, the final stages of the virus that wiped out the adults are revealed in harrowing flashbacks. The deadly disease deteriorated the mind as well as the body, transforming parents and loved ones into violent, sunken-eyed strangers. This device is utilized throughout the film as we are introduced to a handful of fellow survivors, to masterful effect. As each new relationship seems to edge Evie and Fran closer to danger, these regressions serve as telling insights into the natures of the children the girls become tentatively allied with. Even the most explosive characters are given surprising depth within this structure, making it extremely difficult to dislike or root against any of them, though many certainly earn one’s disdain throughout the run.

The siblings first befriend Alice (Justine Rodgers) after Evie witnesses her receiving a beating from a group of girls in the house they’re squatting in. The decision to take in this shell-shocked peer turns out to be a mistake, as the tormentors return to steal all of the girls’ food. Alice leads them to a commune in an abandoned monastery in the woods, where Evie demands their provisions be returned. This stand sparks the interest of Helman (Adam Tyrrell), who shares the unofficial leadership duties with his unstable girlfriend Grace (Laoise Barrett), whose sporadic fits of manic depression have become a burden to him.

The internal power struggle unwittingly created by the appearance of Evie and Fran is further exacerbated when Cass arrives with her entourage, returning after being asked to leave months prior. The reason behind her expulsion from the home takes “Dawn” down even darker and more disturbing paths, and also begs the same unthinkable query Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” scorched into the minds of its readers: What is left to eat once there is no more preserved food to be discovered?

Though absent until the final third, Ellen Mullen owns her brief screen time as the soulless, conniving Cass, delivering her justifications in mannered tones that mask a deep madness. Not without her own tragic pathos, she’s a terrifying creation, performed by Mullen with the cool restraint of a seasoned professional.

The entire cast of newcomers is uniformly spot-on, the young actors bringing aching nuance to characters that are at turns abrasive and brutally violent. This is much less apocalyptic horror story than ensemble character piece, and the few scenes where the kids are allowed to be kids (giggly girls dishing on the others in hushed tones, two boys playing a spirited card game) only add to the overall melancholy of the entire piece. Even as Evie reads passages from “Railway Children” to Fran in an attempt to maintain a tentative link to humanity, we are subjected to visions of their mother (Jennifer Graham) in the throes of the sickness, feverishly reciting from the pages as her daughters cower in revulsion and fear. “Dawn” never lets you off the hook for very long.

Figgis has amassed an extremely talented team behind the camera as well, consisting mostly of him. As spare and bleak as the settings (Did all of the furniture perish in the plague as well?), his direction nonetheless strikes a chord with its palpable atmosphere. His sure-footed photography is aided enormously by Michael Richard Plowman’s brilliant original score, which fluctuates fluidly between sinister and jarring. If there is a major quibble to be made, it would be the movie’s length.

At 106 minutes it feels decidedly inflated, and a few scenes in particular could have benefited from more judicious editing on the film maker’s part. The first encounter at the commune is the most offending example, dragging out nearly twice as long as the exchange required. A couple of the flashbacks could have also been tightened for overall effectiveness. On the flip side of this coin, I thought the character of Cass should have been further explored, but unfortunately she arrives far too late in the day to have any real impact on the outcome.

“Children of a Darker Dawn” is a sad, engrossing morality tale that has just recently been released on video and demand here in the states. Though not the standard genre offering, it finds true horror within the memories and broken psyches of its doomed leads. It may be tough to watch at times, but it’s damn near impossible to forget once the credits roll. This one will stick with you, friends.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews