“When the scientist Fechner disappears in the surface of the mysterious Solaris ocean, the experienced helicopter pilot Henri Berton crosses a fog seeking out Fechner and has weird visions. His statement is presented to a commission of scientists that believe he had hallucinations. However, the widowed psychologist Kris Kelvin is assigned to the space station that orbits Solaris to check the mental health of the three remaining scientists that are still working there. He first meets Doctor Snaut, who tells him that Doctor. Gibarian committed suicide, and later he meets Doctor Sartorius and he realizes that the scientists have strange behaviors. When he encounters his wife Hari, who died ten years ago, in the space station, the scientists explain to Kris that the Solaris ocean has the ability to materialize the innermost thoughts in neutrons beings. Kris questions whether the appearance of his beloved wife is a curse or a blessing.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

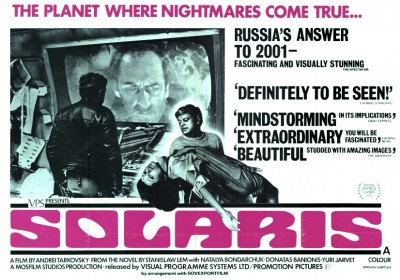

Newcomers to the genre often think a science fiction story must be about technology. Bzzt! Wrong. Some of the questions that science fiction tackles best are psychological, philosophical and metaphysical. Because it allows bizarre new perspectives, science fiction can give us new insights into traditionally difficult areas of thought. The masterly Russian film Solaris (1972), adapted from a philosophical science fiction novel from Polish author Stanislaw Lem, illustrates this point perfectly. It is, however, a rather long film (166 minutes) paced much more slowly than we are used to in the West, and there’s no doubt that some of its viewers have been left baffled and sometimes bored. When dragged back for a second viewing, they usually like it more.

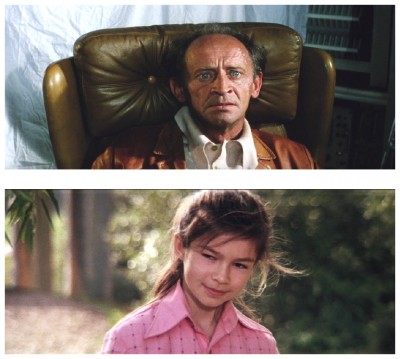

The film opens on Earth at a country homestead outside Moscow, where we meet Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), the space scientist about to leave on a mission. We learn that he has difficulty in expressing his love for his father (Nikolay Grinko). This prologue – damp, green, rippling sedges, water meadows, a galloping horse – is very evocative and establishes the sense of transience and mutability that is to permeate the film. Director Andrei Tarkovsky, one of Russia’s greatest filmmakers ever, has learned the secret of surrealist visions: If you stare at an object long enough it attains an intense significance. So it is with the galloping horse, so it is with a winter landscape painting by Breughel, and so it is with all the images of screens, glasses, windows and obstructions. Although Tarkovsky considered it the least favourite of his films, Solaris remains one of the filmmaker’s most popular works among Western audiences.

The film opens on Earth at a country homestead outside Moscow, where we meet Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), the space scientist about to leave on a mission. We learn that he has difficulty in expressing his love for his father (Nikolay Grinko). This prologue – damp, green, rippling sedges, water meadows, a galloping horse – is very evocative and establishes the sense of transience and mutability that is to permeate the film. Director Andrei Tarkovsky, one of Russia’s greatest filmmakers ever, has learned the secret of surrealist visions: If you stare at an object long enough it attains an intense significance. So it is with the galloping horse, so it is with a winter landscape painting by Breughel, and so it is with all the images of screens, glasses, windows and obstructions. Although Tarkovsky considered it the least favourite of his films, Solaris remains one of the filmmaker’s most popular works among Western audiences.

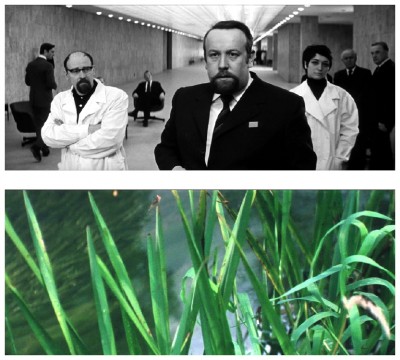

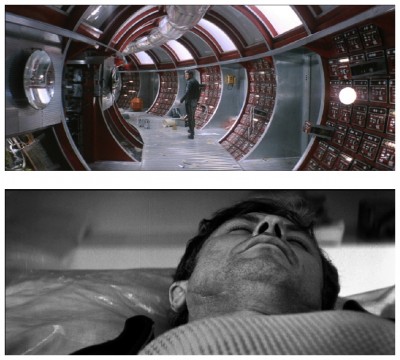

It features many of the aesthetic conceits, visual motifs and prominent themes that characterised Tarkovsky’s work, from his student film The Steamroller And The Violin (1962) to his final film The Sacrifice (1986). Through a series of slow, graceful tracking shots and meticulously composed long takes, Solaris transports its viewers from the lush natural beauty of an agrarian Russian landscape through the congested traffic of a concrete urban sprawl to, finally, a dilapidated space station orbiting a distant planet named Solaris. When the new conscript Kelvin arrives there, he finds it shabby, badly maintained and seemingly unattended. Later, however, two very uncommunicative fellow scientists are found lurking and frightened in their laboratories. They are accompanied by strange half-glimpsed figures. Beneath the station we see the ever-changing ocean of Solaris, and we learn that the planet may be sentient – one giant living thing. But how would such a god-like creature communicate?

It features many of the aesthetic conceits, visual motifs and prominent themes that characterised Tarkovsky’s work, from his student film The Steamroller And The Violin (1962) to his final film The Sacrifice (1986). Through a series of slow, graceful tracking shots and meticulously composed long takes, Solaris transports its viewers from the lush natural beauty of an agrarian Russian landscape through the congested traffic of a concrete urban sprawl to, finally, a dilapidated space station orbiting a distant planet named Solaris. When the new conscript Kelvin arrives there, he finds it shabby, badly maintained and seemingly unattended. Later, however, two very uncommunicative fellow scientists are found lurking and frightened in their laboratories. They are accompanied by strange half-glimpsed figures. Beneath the station we see the ever-changing ocean of Solaris, and we learn that the planet may be sentient – one giant living thing. But how would such a god-like creature communicate?

Kelvin soon finds out when he wakes one morning in his cabin to find his wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) next to him. At first it all seems the most natural thing in the world and, for a moment, he simply accepts her presence. Then he remembers where he is and that Hari had committed suicide. Attempting to exorcise this phantom, he tricks her into a space pod and fires it off. From within we hear inhuman sounds and witness the screeching metal buckling outwards as she tries to escape before she is jettisoned. But soon another Hari materialises, and it is suggested that these ‘phantoms’ might actually be ‘messages’ sent by Solaris.

Kelvin soon finds out when he wakes one morning in his cabin to find his wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) next to him. At first it all seems the most natural thing in the world and, for a moment, he simply accepts her presence. Then he remembers where he is and that Hari had committed suicide. Attempting to exorcise this phantom, he tricks her into a space pod and fires it off. From within we hear inhuman sounds and witness the screeching metal buckling outwards as she tries to escape before she is jettisoned. But soon another Hari materialises, and it is suggested that these ‘phantoms’ might actually be ‘messages’ sent by Solaris.

I’m not going to try to describe the whole film, it’s too rich and densely textured. It’s enough to say that the second Hari comes to realise that she is a copy, recreated by Solaris from Kelvin’s memory. But at the same time she feels herself to be quite real, proving her humanity paradoxically at one point when she attempts suicide (again) to save Kelvin any further distress. The grueling scene where she drinks liquid oxygen must be the envy of many horror filmmakers. One day Hari is simply not there any more. Perhaps her function as a ‘message’ from Solaris has ended. The sensitive Kelvin is stunned and, in a completely unexpected ending, we see him descend to the planet’s surface where a temporary island has been cast up by the protean ocean. On this island is a pleasant old Russian house, it is raining and dimly visible within, seen through a window streaming with water, is Kelvin’s father who cannot hear or see his son reaching out to him. It is a powerfully poignant image that perfectly sums up the themes of this extraordinary film.

I’m not going to try to describe the whole film, it’s too rich and densely textured. It’s enough to say that the second Hari comes to realise that she is a copy, recreated by Solaris from Kelvin’s memory. But at the same time she feels herself to be quite real, proving her humanity paradoxically at one point when she attempts suicide (again) to save Kelvin any further distress. The grueling scene where she drinks liquid oxygen must be the envy of many horror filmmakers. One day Hari is simply not there any more. Perhaps her function as a ‘message’ from Solaris has ended. The sensitive Kelvin is stunned and, in a completely unexpected ending, we see him descend to the planet’s surface where a temporary island has been cast up by the protean ocean. On this island is a pleasant old Russian house, it is raining and dimly visible within, seen through a window streaming with water, is Kelvin’s father who cannot hear or see his son reaching out to him. It is a powerfully poignant image that perfectly sums up the themes of this extraordinary film.

Promoted during its release in America as a Soviet response to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Solaris bears little resemblance to Kubrick’s classic. Indeed, Tarkovsky went to great lengths to avoid miring his work with special effects, technobabble and other genre trappings. Rather, he used Lem’s novel as the foundation for tackling complex philosophical concerns, such as the power of nostalgia and memory, the pronounced connection between human beings and their environment, and the importance of love, forgiveness and reconciliation. Audiences expecting scenes of space travel and futuristic sets were therefore disappointed by Tarkovsky’s low-tech approach. However, time has been kind to Solaris, and it is now considered one of the most provocative science fiction films ever made.

Promoted during its release in America as a Soviet response to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Solaris bears little resemblance to Kubrick’s classic. Indeed, Tarkovsky went to great lengths to avoid miring his work with special effects, technobabble and other genre trappings. Rather, he used Lem’s novel as the foundation for tackling complex philosophical concerns, such as the power of nostalgia and memory, the pronounced connection between human beings and their environment, and the importance of love, forgiveness and reconciliation. Audiences expecting scenes of space travel and futuristic sets were therefore disappointed by Tarkovsky’s low-tech approach. However, time has been kind to Solaris, and it is now considered one of the most provocative science fiction films ever made.

Empire Magazine’s list of The Hundred Best Films Of World Cinema ranked the movie at #68, and author Salman Rushdie called the original film a science fiction masterpiece. In 2002 he said, “This exploration of the unreliability of reality and the power of the human unconscious, this great examination of the limits of rationalism and the perverse power of even the most ill-fated love, needs to be seen as widely as possible before it’s transformed by Steven Soderbergh and James Cameron into what they ludicrously threaten will be 2001: A Space Odyssey meets The Last Tango In Paris (1972). What?! Sex in space with floating butter? Tarkovsky must be turning over in his grave!” Needless to say, filmmaker Steven Soderbergh did just that, and released his own adaptation of Solaris (2002) starring George Clooney, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you goodnight and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the rusty bear-trap known as Hollywoodland for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

Empire Magazine’s list of The Hundred Best Films Of World Cinema ranked the movie at #68, and author Salman Rushdie called the original film a science fiction masterpiece. In 2002 he said, “This exploration of the unreliability of reality and the power of the human unconscious, this great examination of the limits of rationalism and the perverse power of even the most ill-fated love, needs to be seen as widely as possible before it’s transformed by Steven Soderbergh and James Cameron into what they ludicrously threaten will be 2001: A Space Odyssey meets The Last Tango In Paris (1972). What?! Sex in space with floating butter? Tarkovsky must be turning over in his grave!” Needless to say, filmmaker Steven Soderbergh did just that, and released his own adaptation of Solaris (2002) starring George Clooney, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you goodnight and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the rusty bear-trap known as Hollywoodland for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews