SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Journalists of the London Daily Express investigate reports of strange phenomena occurring all over the world, such as flooding in the Sahara, unseasonable blizzards in New York, and violent tornadoes in the Soviet Union. All over England, temperatures are on the rise, girls in bikinis are everywhere, and wonderful special effects mists are blanketing the Thames River. Top scientists at the Meteorological Centre refuse to give any official explanation, which makes the newspaper editor suspicious. He orders science reporter Bill Maguire and alcoholic columnist Peter Stenning to dig for information. When Peter begins a romance with Meteorological Centre secretary Jeannie Craig, he learns from her certain clues that there has indeed been a cover-up, and he begins to sober up, so that he may win her love. Ten days before the film begins, two nuclear bombs had been exploded, one at the North Pole by the Soviet Union, the other at the South Pole by the United States. Nobody noticed before now that they were set almost simultaneously, until the Chief Editor, in a conference with his reporters, draws a line from London to New Zealand, showing the path that floods and other catastrophes have created in a devastating line. Stenning gathers from hints Jeannie gives him that the two explosions shifted the Earth’s orbit and set it on a course toward the sun. As water becomes scarce, the British government takes emergency measures to control hysteria, rampant looting, and rioting by teenagers. The only possible solution is for another explosion of bombs that will restore the Earth’s orbit. On detonation day, Stenning heroically makes his way through a wasteland to the newsroom to write a story that will prepare for the results of the blasts. He instructs the typesetters to prepare two front pages. One has the headline WORLD SAVED, the other WORLD DOOMED.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

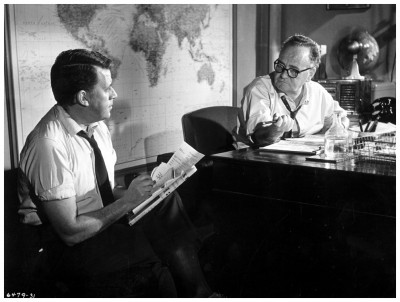

The British-made science fiction film The Day You Earth Caught Fire (1961) was produced, directed and co-written by Val Guest. It begins with strange weather conditions being experienced all over the world, the reason for which is a complete mystery until the London Daily Express science editor (Leo McKern) uncovers, with the help of another Express reporter (Edward Judd), the truth that the governments of the world are trying to hush-up: Two atomic detonations, one at the North Pole and one at the South, have pushed the world out of its orbit and set it on a course towards the sun. When the news is released there is, predictably, panic across the world, but the film centres on events in London. As the temperature rises and the Thames dries up, forcing people to queue for water rations, rioting and looting break out. The film ends on a rather ambiguous note: Four nuclear bombs are to be exploded simultaneously in different parts of the world with the intention of pushing the planet back into its correct orbit. The final shot shows two Daily Express headlines prepared. One reads ‘World Saved’, the other ‘World Doomed’.

Val Guest’s initial career was as an actor, appearing in various productions in London theatres and in a few early film roles, before he gave up acting and moved into writing. In the early thirties he was the London correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter before he began working on film screenplays for Gainsborough Pictures, his first being No Monkey Business (1935). He wrote screenplays for the rest of the decade, including scripts for Will Hay as well as some film scores, before becoming a director with his debut feature Miss London Limited (1943). He went on to direct, produce and script a huge number of films over the following forty years, with perhaps his best known work being the first two Hammer horror films The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass II (1957). He also directed the cult film The Abominable Snowman (1957) and wrote the screenplay for When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth (1970). Guest was one of several directors to work on the James Bond parody Casino Royale (1967) and, during the seventies, he directed soft-p*rn comedies like Au Pair Girls (1972) and Confessions Of A Window Cleaner (1974), and his final feature film The Boys In Blue (1982) which was actually a remake of an earlier picture called Ask A Policeman (1939) which Guest himself had co-written.

Val Guest’s initial career was as an actor, appearing in various productions in London theatres and in a few early film roles, before he gave up acting and moved into writing. In the early thirties he was the London correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter before he began working on film screenplays for Gainsborough Pictures, his first being No Monkey Business (1935). He wrote screenplays for the rest of the decade, including scripts for Will Hay as well as some film scores, before becoming a director with his debut feature Miss London Limited (1943). He went on to direct, produce and script a huge number of films over the following forty years, with perhaps his best known work being the first two Hammer horror films The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass II (1957). He also directed the cult film The Abominable Snowman (1957) and wrote the screenplay for When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth (1970). Guest was one of several directors to work on the James Bond parody Casino Royale (1967) and, during the seventies, he directed soft-p*rn comedies like Au Pair Girls (1972) and Confessions Of A Window Cleaner (1974), and his final feature film The Boys In Blue (1982) which was actually a remake of an earlier picture called Ask A Policeman (1939) which Guest himself had co-written.

I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Guest, when we met on the set of the 1976 television show Space 1999: “It was entirely my own idea. I’d been reading about all these people writing to The Times and saying how all these atomic tests were changing the atmosphere and the weather, and other people were saying, ‘What absolute rubbish!’ but I suddenly thought what if these tests did do that? What could happen? And these days I’m amazed when I see headlines practically the same as the ones we had printed for the Express in our film, such as ‘Incredible Summer!’, ‘Floods Sweep Europe!’ and ‘New Ice Age On The Way!’ Everything that was in that picture has been happening recently. I read about an enormous amount of ice melting at the North Pole that had made a displacement of water and caused the Earth to shift, very slightly, on its axis. And this is not very far off reversing the Poles as I did in my picture.”

I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Guest, when we met on the set of the 1976 television show Space 1999: “It was entirely my own idea. I’d been reading about all these people writing to The Times and saying how all these atomic tests were changing the atmosphere and the weather, and other people were saying, ‘What absolute rubbish!’ but I suddenly thought what if these tests did do that? What could happen? And these days I’m amazed when I see headlines practically the same as the ones we had printed for the Express in our film, such as ‘Incredible Summer!’, ‘Floods Sweep Europe!’ and ‘New Ice Age On The Way!’ Everything that was in that picture has been happening recently. I read about an enormous amount of ice melting at the North Pole that had made a displacement of water and caused the Earth to shift, very slightly, on its axis. And this is not very far off reversing the Poles as I did in my picture.”

“Actually I wrote the treatment for the film seven years before anyone would let me make it. Whenever I had a successful film the company concerned would say, ‘What would you like to do next?’ and I would say, “Well, I’d like to do this science fiction story I’ve got.” They’d immediately say no one wants to know about the bomb, and so the treatment got pushed aside and pushed aside. Eventually I found a producer here called Steven Pallos who was interested and between us we rustled up the money. I had made a lot of money from Expresso Bongo, a film I’d made in 1960, so I ploughed it into the film, and Pallos and I became partners in producing it ourselves. Then I got a hold of Wolf Mankowitz and said, ‘Do you want to come in on this? I can’t afford to pay you yet but read it and let’s do it together’. So we wrote the script together based on my treatment, and we both made an enormous amount of money on it, along with Steven Pallos. The money is still coming in.”

“Actually I wrote the treatment for the film seven years before anyone would let me make it. Whenever I had a successful film the company concerned would say, ‘What would you like to do next?’ and I would say, “Well, I’d like to do this science fiction story I’ve got.” They’d immediately say no one wants to know about the bomb, and so the treatment got pushed aside and pushed aside. Eventually I found a producer here called Steven Pallos who was interested and between us we rustled up the money. I had made a lot of money from Expresso Bongo, a film I’d made in 1960, so I ploughed it into the film, and Pallos and I became partners in producing it ourselves. Then I got a hold of Wolf Mankowitz and said, ‘Do you want to come in on this? I can’t afford to pay you yet but read it and let’s do it together’. So we wrote the script together based on my treatment, and we both made an enormous amount of money on it, along with Steven Pallos. The money is still coming in.”

“A lot of it was actually shot in the Daily Express offices. We were allowed to do that because I brought Arthur Christiansen, who had been the paper’s greatest editor, into the picture and organised it with the paper’s owner Lord Beaverbrook. But it was an enormously difficult picture to make and we had to pull every known trick in the book to get some of the scenes we wanted in London. For instance, I had to show Fleet Street completely deserted and desolate with windows boarded up, overturned buses and cars, and an enormous amount layer of dust over everything, and I was told by the police, ‘No way can you do this to Fleet Street!’ Well, we argued and argued. We went to see the top people at Scotland Yard, Chris called the Home Office, the Prime Minister, everyone, and finally they agreed to give us Fleet Street for three minutes at a time providing it wouldn’t hold up traffic at peak periods.”

“A lot of it was actually shot in the Daily Express offices. We were allowed to do that because I brought Arthur Christiansen, who had been the paper’s greatest editor, into the picture and organised it with the paper’s owner Lord Beaverbrook. But it was an enormously difficult picture to make and we had to pull every known trick in the book to get some of the scenes we wanted in London. For instance, I had to show Fleet Street completely deserted and desolate with windows boarded up, overturned buses and cars, and an enormous amount layer of dust over everything, and I was told by the police, ‘No way can you do this to Fleet Street!’ Well, we argued and argued. We went to see the top people at Scotland Yard, Chris called the Home Office, the Prime Minister, everyone, and finally they agreed to give us Fleet Street for three minutes at a time providing it wouldn’t hold up traffic at peak periods.”

“So we worked it out like a battle and timed it all perfectly – we would rehearse the scene when all the traffic was going by – the police had put up ‘No Parking’ signs all the way along the street from the Express building up to the Law Courts – and when we had our three minutes a whistle would be blown and they’d hold the traffic up at the Law Courts end. Then two motorcycle policemen would tear up the street knocking down all the ‘No Parking’ signs followed by our prop van with about four guys shoveling out all this Fullers Earth onto the road, so then we had Fleet Street covered in a haze of dust and dirt, and then we’d shoot our scene, all within three minutes. And if we didn’t get the take we wanted then we we had to let the whole thing go for at least a quarter of an hour. We had other props lying around as well, girders and things, and we had the front of the Express building so that it looked as if it had been shattered. One day the old man himself, Beaverbrook, went by and saw this and was aghast. He called up and cried, ‘What in Christ’s name has happened to the Express?’ Later he said to me, ‘I don’t care what you do with the offices or the building, but the day the Daily Express doesn’t come out, you’re finished’.”

“So we worked it out like a battle and timed it all perfectly – we would rehearse the scene when all the traffic was going by – the police had put up ‘No Parking’ signs all the way along the street from the Express building up to the Law Courts – and when we had our three minutes a whistle would be blown and they’d hold the traffic up at the Law Courts end. Then two motorcycle policemen would tear up the street knocking down all the ‘No Parking’ signs followed by our prop van with about four guys shoveling out all this Fullers Earth onto the road, so then we had Fleet Street covered in a haze of dust and dirt, and then we’d shoot our scene, all within three minutes. And if we didn’t get the take we wanted then we we had to let the whole thing go for at least a quarter of an hour. We had other props lying around as well, girders and things, and we had the front of the Express building so that it looked as if it had been shattered. One day the old man himself, Beaverbrook, went by and saw this and was aghast. He called up and cried, ‘What in Christ’s name has happened to the Express?’ Later he said to me, ‘I don’t care what you do with the offices or the building, but the day the Daily Express doesn’t come out, you’re finished’.”

“We also had terrible trouble getting Trafalgar Square for the sequence where we had a demonstration and a fight in the square. We had to book it months in advance with the police because they rent out the square to various groups. Our big problem was money, of course. We didn’t have a very big budget – we made it for under three hundred thousand pounds, though today to make the same film you’d need a ridiculous amount – so we had to use money-saving effects. Les Bowie did the special effects for me: I gave him a lump sum of money to do them and, of course, he did a hell of a good job. But we had terrible trouble with the sequence where the fog was supposed to come up the Thames and cover everything. We were shooting in Battersea Park beside the river and we had fog machines all over the place – we’d also emptied Battersea Bridge and put all our stuff on it, including a queue of people waiting for water rations – and it happened to be the day that the Queen was opening the Chelsea Flower Show, and the wind suddenly changed and all our fog drifted into Chelsea. Very embarrassing! The police came down and told us to turn off our machines, but while my unit and location manager was saying to the police, ‘Yes, yes, we’ll turn them off,’ we just continued shooting as quickly as possible.”

“We also had terrible trouble getting Trafalgar Square for the sequence where we had a demonstration and a fight in the square. We had to book it months in advance with the police because they rent out the square to various groups. Our big problem was money, of course. We didn’t have a very big budget – we made it for under three hundred thousand pounds, though today to make the same film you’d need a ridiculous amount – so we had to use money-saving effects. Les Bowie did the special effects for me: I gave him a lump sum of money to do them and, of course, he did a hell of a good job. But we had terrible trouble with the sequence where the fog was supposed to come up the Thames and cover everything. We were shooting in Battersea Park beside the river and we had fog machines all over the place – we’d also emptied Battersea Bridge and put all our stuff on it, including a queue of people waiting for water rations – and it happened to be the day that the Queen was opening the Chelsea Flower Show, and the wind suddenly changed and all our fog drifted into Chelsea. Very embarrassing! The police came down and told us to turn off our machines, but while my unit and location manager was saying to the police, ‘Yes, yes, we’ll turn them off,’ we just continued shooting as quickly as possible.”

The hassle was worth it. Writers Guest and Mankowitz won the BAFTA that year for Best Screenplay. Arthur Christiansen, former editor of the Daily Express, essentially plays himself, and a very young Michael Caine can be spotted as an uncredited traffic cop. Monte Norman, who was credited with writing Beatnik music in a couple of scenes, would become well known the following year when his James Bond Theme was used in the title sequence of Doctor No (1962). In his commentary on the 2001 DVD release of The Day The Earth Caught Fire, Mr. Guest said that the sound of church bells heard at the very end of the American version had been added by distributor Universal, suggesting that the emergency detonation had succeeded and that the Earth had been saved, no doubt inspired by The War Of The Worlds (1953) which also ends with the joyous ringing of church bells. I’ll leave you to ponder that puzzlement, but not before thanking certain sources for their vital assistance in my research: NME Magazine and Monthly Film Bulletin Magazine. I look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to take you even closer to the event horizon of the insatiable black hole that is Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

The hassle was worth it. Writers Guest and Mankowitz won the BAFTA that year for Best Screenplay. Arthur Christiansen, former editor of the Daily Express, essentially plays himself, and a very young Michael Caine can be spotted as an uncredited traffic cop. Monte Norman, who was credited with writing Beatnik music in a couple of scenes, would become well known the following year when his James Bond Theme was used in the title sequence of Doctor No (1962). In his commentary on the 2001 DVD release of The Day The Earth Caught Fire, Mr. Guest said that the sound of church bells heard at the very end of the American version had been added by distributor Universal, suggesting that the emergency detonation had succeeded and that the Earth had been saved, no doubt inspired by The War Of The Worlds (1953) which also ends with the joyous ringing of church bells. I’ll leave you to ponder that puzzlement, but not before thanking certain sources for their vital assistance in my research: NME Magazine and Monthly Film Bulletin Magazine. I look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to take you even closer to the event horizon of the insatiable black hole that is Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews