SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Paranoid Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper of Burpelson Air Force Base, he believing that fluoridation of the American water supply is a Soviet plot to poison the U.S. populace, is able to deploy through a back door mechanism a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union without the knowledge of his superiors, including the Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Buck Turgidson, and President Merkin Muffley. Only Ripper knows the code to recall the B-52 bombers and he has shut down communication in and out of Burpelson as a measure to protect this attack. Ripper’s executive officer, RAF Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (on exchange from Britain), who is being held at Burpelson by Ripper, believes he knows the recall codes if he can only get a message to the outside world. Meanwhile at the Pentagon War Room, key persons including Muffley, Turgidson and nuclear scientist and adviser, a former Nazi named Dr. Strangelove, are discussing measures to stop the attack or mitigate its blow-up into an all out nuclear war with the Soviets. Against Turgidson’s wishes, Muffley brings Soviet Ambassador Alexi de Sadesky into the War Room, and get his boss, Soviet Premier Dimitri Kisov, on the hot line to inform him of what’s going on. The Americans in the War Room are dismayed to learn that the Soviets have a yet as unannounced Doomsday Device to detonate if any of their key targets are hit. As Ripper, Mandrake and those in the War Room try and work the situation to their end goal, Major T.J. ‘King’ Kong, one of the B-52 bomber pilots, is working on his own agenda of deploying his bomb where ever he can on enemy soil if he can’t make it to his intended target.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Stanley Kubrick‘s Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964), is a grim fairy tale whose introductory phrase might well be, not “Once Upon A Time,” but “What If…?” What if an insane US Army General initialised a B-52 attack on the Soviet Union? What if he were to commit suicide before divulging the recall code? What if, when that code had somehow been deciphered, one of the planes did not receive the recall code? What if the Russians had constructed an ultimate weapon of mass destruction, a doomsday machine impossible to defuse in the event of a nuclear attack? The only conceivable answer to that series of not-so-hypothetical questions provides the movie with its denouement and, in a sense, its Q.E.D: Mushroom clouds billow gracefully over a depopulated planet while the saccharine voice of Vera Lynn sings the war ballad We’ll Meet Again.

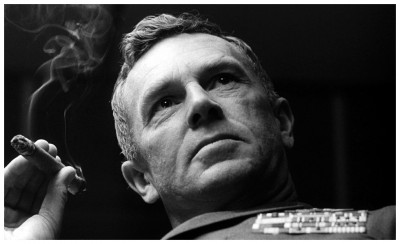

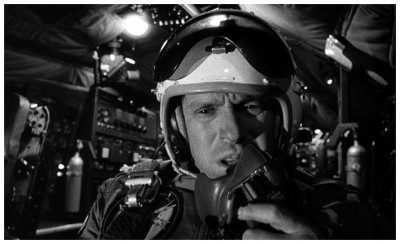

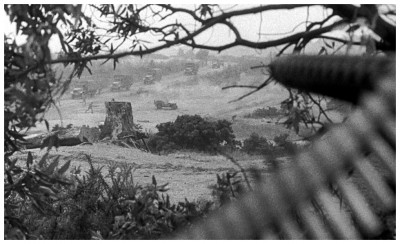

Loosely based on the Peter George novel Red Alert, the movie offers a relentless exposition step-by-step of the strict inflexible logic of unreason, and its warning is perhaps even more urgently timed today than when it was made in the early sixties. Shot in black-and-white camerawork that is either glittering (Ken Adam‘s spectacular War Room set) or grainy hand-held (the attack on Burpelson Air Force Base), Dr. Strangelove is, in narrative terms, black through-and-through. Here, the lighter side is either an illusion or restricted to well above the earth, like in the opening credit sequence where the fueling of B-52s is conceived as balletic copulation to the ironic strains of Try A Little Tenderness. In fact, a current of sexual symbolism is perceptible throughout the entire movie, from the paranoid fears of General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) that the Russians have polluted his ‘precious bodily fluids’ thereby interfering with his sexual prowess, to the moment when Major ‘King’ Kong (Slim Pickens) hurtles cheerfully to his destruction astride an atomic bomb which has become, between his legs, the world’s most potent and grandiose phallus.

Loosely based on the Peter George novel Red Alert, the movie offers a relentless exposition step-by-step of the strict inflexible logic of unreason, and its warning is perhaps even more urgently timed today than when it was made in the early sixties. Shot in black-and-white camerawork that is either glittering (Ken Adam‘s spectacular War Room set) or grainy hand-held (the attack on Burpelson Air Force Base), Dr. Strangelove is, in narrative terms, black through-and-through. Here, the lighter side is either an illusion or restricted to well above the earth, like in the opening credit sequence where the fueling of B-52s is conceived as balletic copulation to the ironic strains of Try A Little Tenderness. In fact, a current of sexual symbolism is perceptible throughout the entire movie, from the paranoid fears of General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) that the Russians have polluted his ‘precious bodily fluids’ thereby interfering with his sexual prowess, to the moment when Major ‘King’ Kong (Slim Pickens) hurtles cheerfully to his destruction astride an atomic bomb which has become, between his legs, the world’s most potent and grandiose phallus.

Kubrick, who wrote the script with Terry Southern, originally planned to film Peter George’s novel as a serious suspense story: “As I tried to build the detail for a scene, I found myself tossing away what seemed to me to be very truthful insights because I was afraid the audience would laugh. After a few weeks I realised that these incongruous bits of reality were closer to the truth than anything else I was able to imagine. And it was at this point I decided to treat the story as a nightmare comedy.” The realism of the settings and the machinery, particularly the interior of the B-52, gives an added impact to the horrifying absurdity of the action and characters.

Kubrick, who wrote the script with Terry Southern, originally planned to film Peter George’s novel as a serious suspense story: “As I tried to build the detail for a scene, I found myself tossing away what seemed to me to be very truthful insights because I was afraid the audience would laugh. After a few weeks I realised that these incongruous bits of reality were closer to the truth than anything else I was able to imagine. And it was at this point I decided to treat the story as a nightmare comedy.” The realism of the settings and the machinery, particularly the interior of the B-52, gives an added impact to the horrifying absurdity of the action and characters.

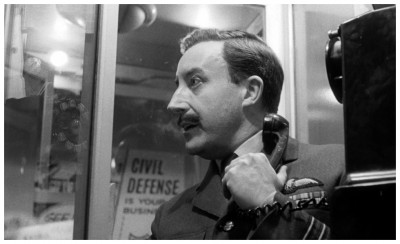

Major Kong was one of the roles assigned to Peter Sellers by Kubrick but, during preproduction, Sellers had enormous difficulties finding the right voice and, subsequently, the rest of the character. At that time Sellers was having a rather intense affair with British actress Janette Scott of The Day Of The Triffids (1962). Disturbed by the intensity of his frustration, Scott advised Sellers not to tackle a fourth character. As it happened, he supposedly broke his ankle, and Kubrick was obliged to replace him with the excellent Slim Pickens, but only after John Wayne and Dan Blocker had both turned the role down due to the left-wing nature of the script. So Sellers ‘only’ played three characters: Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, an archetypal English RAF officer who manages to decode the ravings of General Ripper doodled in a notepad; United States President Merkin Muffley; and the sinister Dr. Strangelove.

Major Kong was one of the roles assigned to Peter Sellers by Kubrick but, during preproduction, Sellers had enormous difficulties finding the right voice and, subsequently, the rest of the character. At that time Sellers was having a rather intense affair with British actress Janette Scott of The Day Of The Triffids (1962). Disturbed by the intensity of his frustration, Scott advised Sellers not to tackle a fourth character. As it happened, he supposedly broke his ankle, and Kubrick was obliged to replace him with the excellent Slim Pickens, but only after John Wayne and Dan Blocker had both turned the role down due to the left-wing nature of the script. So Sellers ‘only’ played three characters: Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, an archetypal English RAF officer who manages to decode the ravings of General Ripper doodled in a notepad; United States President Merkin Muffley; and the sinister Dr. Strangelove.

What is astonishing about this triple achievement is precisely the extent to which it was ‘triple’. Kubrick’s reassurances that the feat, if successful, would represent much more than a simple gimmick and was triumphantly vindicated. Contrary to his work in The Mouse That Roared (1959), one was rarely conscious of the virtuoso aspect of an actor giving three separate performances in a single movie – Sellers appeared to be three separate actors. There seemed to be no real behavioral relation between Mandrake and Muffley, for example, beyond the fact that they were both ineffectual milksops in positions of authority. Mandrake’s hyper-developed sense of proprieties is defeated only by Colonel ‘Bat’ Guano (Keenan Wynn) who, obsessed with what he calls ‘deviated preverts’ dutifully prevents Mandrake from destroying Army property, namely a Coca-Cola machine from which a coin might be illegally extracted in order to make a phone call and save the world from extinction.

What is astonishing about this triple achievement is precisely the extent to which it was ‘triple’. Kubrick’s reassurances that the feat, if successful, would represent much more than a simple gimmick and was triumphantly vindicated. Contrary to his work in The Mouse That Roared (1959), one was rarely conscious of the virtuoso aspect of an actor giving three separate performances in a single movie – Sellers appeared to be three separate actors. There seemed to be no real behavioral relation between Mandrake and Muffley, for example, beyond the fact that they were both ineffectual milksops in positions of authority. Mandrake’s hyper-developed sense of proprieties is defeated only by Colonel ‘Bat’ Guano (Keenan Wynn) who, obsessed with what he calls ‘deviated preverts’ dutifully prevents Mandrake from destroying Army property, namely a Coca-Cola machine from which a coin might be illegally extracted in order to make a phone call and save the world from extinction.

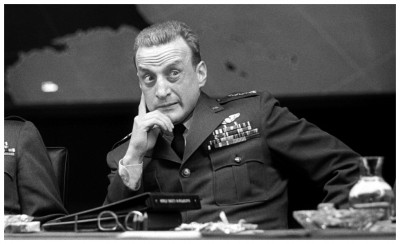

On the other hand, Merkin Muffley – small, bald and entirely lacking in Presidential charisma – is persistently bypassed by events as they are reported to him by General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) who, offended by the President’s criticism of a system that is heading for a global holocaust, protests, “I don’t think it’s fair to condemn a whole program just because of a single slip-up!” President Muffley is well-meaning but totally bewildered, apologetically breaking the bad news to his tipsy Soviet counterpart on the hot-line, “I’m sorrier than you, Dimitri…no, you couldn’t be sorrier than I am, Dimitri…”

On the other hand, Merkin Muffley – small, bald and entirely lacking in Presidential charisma – is persistently bypassed by events as they are reported to him by General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) who, offended by the President’s criticism of a system that is heading for a global holocaust, protests, “I don’t think it’s fair to condemn a whole program just because of a single slip-up!” President Muffley is well-meaning but totally bewildered, apologetically breaking the bad news to his tipsy Soviet counterpart on the hot-line, “I’m sorrier than you, Dimitri…no, you couldn’t be sorrier than I am, Dimitri…”

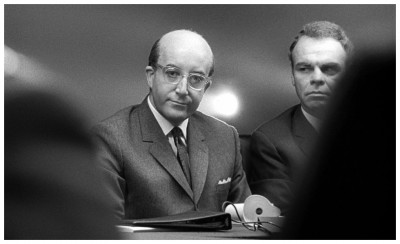

But the most audacious stroke of all is undoubtedly Dr. Strangelove himself. Only near the very end of the movie (and the world) are we allowed to see him properly, with his crinkled wavy coiffure and maniacally glinting eyes, like some sort of exclusively nocturnal creature that thrives on reveries of apocalypse. His artificial metal arm jerks involuntarily into ill-timed Nazi salutes, or clamps itself firmly around his own throat. He revels with guttural gusto at the prospect of spending his post-nuclear existence surrounded by a harem of generously endowed young women, all conscientiously propagating the species. And his apotheosis – rising triumphantly from his wheelchair with the demented cry, “Mein führer! I can walk!” – coincides with the final catastrophe. Strangelove may be a caricature, but a caricature of pure genius.

But the most audacious stroke of all is undoubtedly Dr. Strangelove himself. Only near the very end of the movie (and the world) are we allowed to see him properly, with his crinkled wavy coiffure and maniacally glinting eyes, like some sort of exclusively nocturnal creature that thrives on reveries of apocalypse. His artificial metal arm jerks involuntarily into ill-timed Nazi salutes, or clamps itself firmly around his own throat. He revels with guttural gusto at the prospect of spending his post-nuclear existence surrounded by a harem of generously endowed young women, all conscientiously propagating the species. And his apotheosis – rising triumphantly from his wheelchair with the demented cry, “Mein führer! I can walk!” – coincides with the final catastrophe. Strangelove may be a caricature, but a caricature of pure genius.

Produced at the same time as Dr. Strangelove but not released until six months later, Fail Safe (1964) was directed by Sidney Lumet, and superficially appears to be a serious version of Dr. Strangelove. A mechanical malfunction causes an American bomber to obliterate Moscow by mistake and, to avert a nuclear war, the American government placates the understandably pissed-off Russians by dropping a hydrogen bomb on New York. There is something terribly unhealthy about such a story. A far more straight-faced film than Dr. Strangelove, is ultimately weaker and shabbier because it turns disaster into an excuse for national pride. The disaster itself itself is blamed on a machine instead of the men who put so much trust and pride in their toys. The hero of the piece becomes the brave American President (Henry Fonda) who does what has to be done, and the tragedy is that the Empire State Building becomes ground zero. The novel by Eugene Burd*ck and Harvey Wheeler refers to the President’s sacrifice of New York as “The most sweeping and incredible decision that any man has made,” and ends on a patriotic and upbeat note as the President orders a Medal Of Honour citation be prepared for the General who bombed New York.

Produced at the same time as Dr. Strangelove but not released until six months later, Fail Safe (1964) was directed by Sidney Lumet, and superficially appears to be a serious version of Dr. Strangelove. A mechanical malfunction causes an American bomber to obliterate Moscow by mistake and, to avert a nuclear war, the American government placates the understandably pissed-off Russians by dropping a hydrogen bomb on New York. There is something terribly unhealthy about such a story. A far more straight-faced film than Dr. Strangelove, is ultimately weaker and shabbier because it turns disaster into an excuse for national pride. The disaster itself itself is blamed on a machine instead of the men who put so much trust and pride in their toys. The hero of the piece becomes the brave American President (Henry Fonda) who does what has to be done, and the tragedy is that the Empire State Building becomes ground zero. The novel by Eugene Burd*ck and Harvey Wheeler refers to the President’s sacrifice of New York as “The most sweeping and incredible decision that any man has made,” and ends on a patriotic and upbeat note as the President orders a Medal Of Honour citation be prepared for the General who bombed New York.

If Kubrick had got his hands on that story, the resulting film might have been even funnier than Dr. Strangelove. It’s with that amusing thought in mind I’d like to thank Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker (1973) and Looking Away: Hollywood And Vietnam by Julian Smith (1973) for assisting my research for this article, and politely remind you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

If Kubrick had got his hands on that story, the resulting film might have been even funnier than Dr. Strangelove. It’s with that amusing thought in mind I’d like to thank Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker (1973) and Looking Away: Hollywood And Vietnam by Julian Smith (1973) for assisting my research for this article, and politely remind you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964)

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews