SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

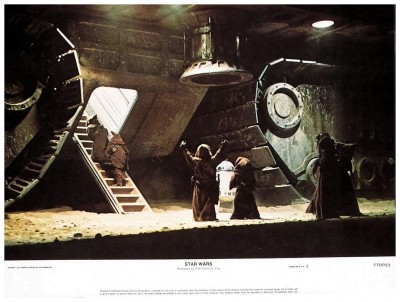

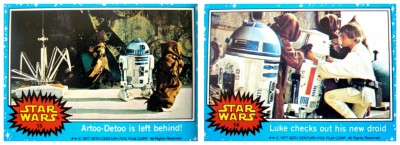

“Luke Skywalker stays with his foster aunt and uncle on a farm on Tatooine. He is desperate to get off this planet and get to the Academy like his friends, but his uncle needs him for the next harvest. Meanwhile, an evil emperor has taken over the galaxy, and has constructed a formidable ‘Death Star’ capable of destroying whole planets. Princess Leia, a leader in the resistance movement, acquires plans of the Death Star, places them in R2-D2, a droid, and sends him off to find Obi-Wan Kenobi. Before he finds him, R2-D2 ends up on the Skywalkers’ farm with his friend C-3PO. R2-D2 then wanders into the desert, and when Luke follows, they eventually come across Obi-Wan. Will Luke, Obi-Wan and the two droids be able to destroy the Death Star, or will the Emperor rule forever?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Star Wars (1977) and its two sequels became a worldwide pop culture phenomenon, spawning hundreds of books, novels, comics, clubs, television series, action figures, trading cards, video games, fan films, records and CDs, videos and DVDs. Sixteen years later a new trilogy of films was released, bringing the overall box-office takings to almost five billion dollars, making it the third-highest grossing film series after the Harry Potter and James Bond franchises. Star Wars owes a lot to the James Bond films, but then it owes a lot to all sorts of movies, such as westerns, serials, swashbucklers, war movies, The Hidden Fortress (1958), The Wizard Of Oz (1939) and even Snow White (1937).

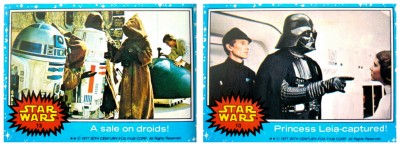

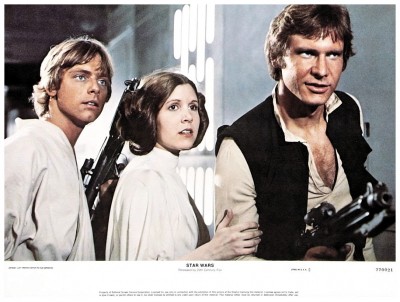

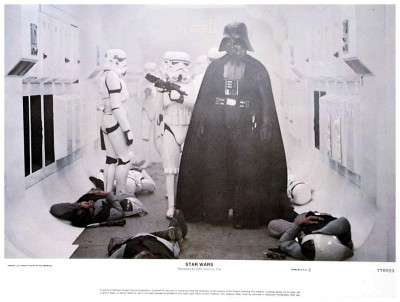

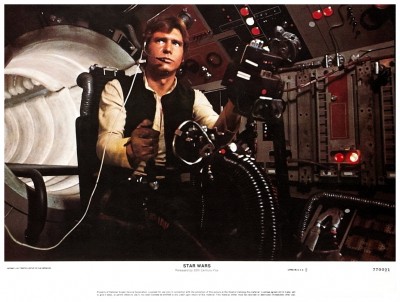

The story concerns a young man named Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) who leaves his uncle’s farm on a small arid planet called Tatooine to help rescue a beautiful princess (Carrie Fisher) from the clutches of the evil Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) who represents a decadent galactic empire. Tarkin’s henchman is a mysterious black-clad giant named Darth Vader (David Prowse voiced by James Earl Jones) and their base is a vast space station called the Death Star which is the size of a small moon and capable of destroying whole planets. With the help of a retired warrior named Kenobi (Sir Alec Guinness), a mercenary smuggler named Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and two cute robots, Luke succeeds in rescuing the princess and destroying the Death Star, but Darth Vader escapes to fight another day.

The story concerns a young man named Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) who leaves his uncle’s farm on a small arid planet called Tatooine to help rescue a beautiful princess (Carrie Fisher) from the clutches of the evil Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) who represents a decadent galactic empire. Tarkin’s henchman is a mysterious black-clad giant named Darth Vader (David Prowse voiced by James Earl Jones) and their base is a vast space station called the Death Star which is the size of a small moon and capable of destroying whole planets. With the help of a retired warrior named Kenobi (Sir Alec Guinness), a mercenary smuggler named Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and two cute robots, Luke succeeds in rescuing the princess and destroying the Death Star, but Darth Vader escapes to fight another day.

The plot could have been lifted from any second-rate science fiction pulp magazine of the thirties, and its intellectual level is that of the old Flash Gordon serials, exactly as creator George Lucas intended. He originally wanted to make a new film version of Flash Gordon but couldn’t obtain rights to the character – instead he wrote a script that incorporated many elements from both the Flash Gordon serials and comic strip. I was lucky enough to run into George on the set of his first long-forgotten television series Maniac Mansion, who told me, “The plot is simple. Good against evil, and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember from the period when I was twelve. The word for this movie is ‘Fun’.”

The plot could have been lifted from any second-rate science fiction pulp magazine of the thirties, and its intellectual level is that of the old Flash Gordon serials, exactly as creator George Lucas intended. He originally wanted to make a new film version of Flash Gordon but couldn’t obtain rights to the character – instead he wrote a script that incorporated many elements from both the Flash Gordon serials and comic strip. I was lucky enough to run into George on the set of his first long-forgotten television series Maniac Mansion, who told me, “The plot is simple. Good against evil, and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember from the period when I was twelve. The word for this movie is ‘Fun’.”

Such a statement practically disarms serious criticism, which is probably what it’s designed to do. The simple-minded dialogue is intentional, so bad that actor Harrison Ford threatened to tie George down and force him to repeat his own dialogue. Gaping holes in the plot or credibility-stretching coincidences are explained away by the claim that it is all a fairy tale set a long time ago in a galaxy far away. There is no justification, therefore, in asking why this particular galaxy seems to be ruled by human beings (of the caucasian variety only) despite the existence of other races, or why the Death Star has such a convenient flaw in its defences, or why the spaceships and explosions make sounds in the vacuum of space. It seems like quibbling to point out that the space battles in the film (choreographed from WWII aerial dogfights) are totally unrealistic because the spaceships would be moving so fast that such close maneuvering would be impossible. It also seems like quibbling to wonder why there’s no lack of gravity in any of the spaceships large or small – there isn’t even a token mention of artificial gravity, that old standby of science fiction authors.

Such a statement practically disarms serious criticism, which is probably what it’s designed to do. The simple-minded dialogue is intentional, so bad that actor Harrison Ford threatened to tie George down and force him to repeat his own dialogue. Gaping holes in the plot or credibility-stretching coincidences are explained away by the claim that it is all a fairy tale set a long time ago in a galaxy far away. There is no justification, therefore, in asking why this particular galaxy seems to be ruled by human beings (of the caucasian variety only) despite the existence of other races, or why the Death Star has such a convenient flaw in its defences, or why the spaceships and explosions make sounds in the vacuum of space. It seems like quibbling to point out that the space battles in the film (choreographed from WWII aerial dogfights) are totally unrealistic because the spaceships would be moving so fast that such close maneuvering would be impossible. It also seems like quibbling to wonder why there’s no lack of gravity in any of the spaceships large or small – there isn’t even a token mention of artificial gravity, that old standby of science fiction authors.

“I just wanted to forget science, that would take care of itself. Stanley Kubrick made the ultimate science fiction movie and it is going to be very hard for somebody to come along and make a better movie, as far as I’m concerned. I didn’t want to make 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), I wanted to make a space fantasy that was there before science took it over in the 1950s. Once the atomic bomb came, everybody got into monsters and science. I think speculative fiction is very valid, but they forgot the fairy tales.”

“I just wanted to forget science, that would take care of itself. Stanley Kubrick made the ultimate science fiction movie and it is going to be very hard for somebody to come along and make a better movie, as far as I’m concerned. I didn’t want to make 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), I wanted to make a space fantasy that was there before science took it over in the 1950s. Once the atomic bomb came, everybody got into monsters and science. I think speculative fiction is very valid, but they forgot the fairy tales.”

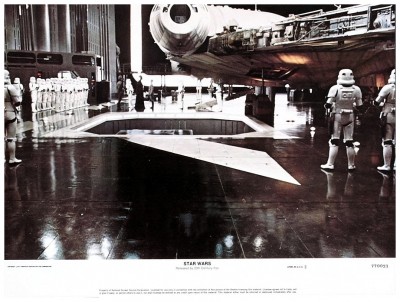

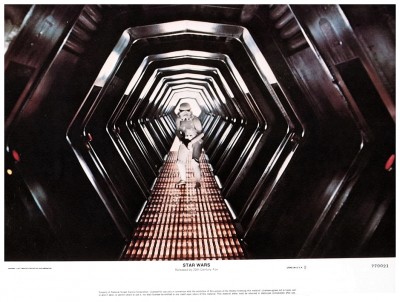

As George willingly admits, Star Wars has been cobbled together from a wide variety of different sources – movies, comics, serials, novels – so we get western clichés like the scene in which Luke returns to the homestead to find it on fire and his relatives massacred, prompting him to vow vengeance, and the scene in the alien cantina mirrors countless western saloon scenes, including the traditional brush with a bounty hunter. Other ingredients are inspired by Frank Herbert’s Dune novels and J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings (both required reading material for students during the sixties), and several scenes seem directly based on science fiction magazine covers by such artists as Ed Emshwiller, John Schoenherr and Kelly Freas. Movies about World War Two also provided a great deal of visual inspiration. Apart from the dogfight footage used to choreograph the battles, the climactic bombing run across the surface of the Death Star was based on movies like The Dam Busters (1955) and 633 Squadron (1964). The lead villain, Tarkin, is the embodiment of every evil Nazi officer to appear on the screen and his imperial soldiers are called, significantly, storm-troopers.

As George willingly admits, Star Wars has been cobbled together from a wide variety of different sources – movies, comics, serials, novels – so we get western clichés like the scene in which Luke returns to the homestead to find it on fire and his relatives massacred, prompting him to vow vengeance, and the scene in the alien cantina mirrors countless western saloon scenes, including the traditional brush with a bounty hunter. Other ingredients are inspired by Frank Herbert’s Dune novels and J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings (both required reading material for students during the sixties), and several scenes seem directly based on science fiction magazine covers by such artists as Ed Emshwiller, John Schoenherr and Kelly Freas. Movies about World War Two also provided a great deal of visual inspiration. Apart from the dogfight footage used to choreograph the battles, the climactic bombing run across the surface of the Death Star was based on movies like The Dam Busters (1955) and 633 Squadron (1964). The lead villain, Tarkin, is the embodiment of every evil Nazi officer to appear on the screen and his imperial soldiers are called, significantly, storm-troopers.

Other sources of material incorporated into Star Wars include Asimov’s Foundation trilogy, with its vast and decadent galactic empire, and such films as The Wizard Of Oz and Snow White: Threepio (Anthony Daniels) reminds us of the Tin Man, and Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew) the Cowardly Lion. Princess Leia has more than a passing resemblance to Snow White, and Artoo-Detoo (Kenny Baker) is no doubt her loyal whistling dwarf. Darth Vader himself is a combination of Doctor Doom and the Black Knight. George has mixed all the ingredients together very skillfully and, as he intended, the result is fun, especially since there’s a nice line of clever humour running through the film, yet it’s hard not to wish that all the magnificent sets, effects, technical expertise and talent hadn’t been used to make something a little more substantial and original. Like many American filmmakers of the last three decades, Lucas seems obsessed by nostalgia – instead of making genuinely original films, the trend is to remake all their favourite old ones.

Other sources of material incorporated into Star Wars include Asimov’s Foundation trilogy, with its vast and decadent galactic empire, and such films as The Wizard Of Oz and Snow White: Threepio (Anthony Daniels) reminds us of the Tin Man, and Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew) the Cowardly Lion. Princess Leia has more than a passing resemblance to Snow White, and Artoo-Detoo (Kenny Baker) is no doubt her loyal whistling dwarf. Darth Vader himself is a combination of Doctor Doom and the Black Knight. George has mixed all the ingredients together very skillfully and, as he intended, the result is fun, especially since there’s a nice line of clever humour running through the film, yet it’s hard not to wish that all the magnificent sets, effects, technical expertise and talent hadn’t been used to make something a little more substantial and original. Like many American filmmakers of the last three decades, Lucas seems obsessed by nostalgia – instead of making genuinely original films, the trend is to remake all their favourite old ones.

The most serious criticism of Star Wars on its initial release was that it embodies Nazi mythology, and several critics noted that the film’s closing victory ceremony was inspired by Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph Of The Will (1935). Was the mystical ‘Force’ which figures so prominently in the film, and provides Luke with the power to destroy the Death Star, an expression of basic Nazi beliefs? Absurdly far-fetched though this may be, the film did reflect a growing tendency among the young to reject rationalism in favour of mysticism. Kenobi instructs Luke saying, “Your eyes can deceive you, don’t trust them. Stretch out with your feelings. Let go of your conscious self and act on instinct.” Sir Alec Guinness, who played Kenobi, was concerned that some people were taking his mystical pronouncements seriously. “I’ve been getting some strange letters from America, from married couples, not teenagers. They think that because I play a wise man in the film I can solve all their problems. The letters say, ‘You’ve altered our lives, you must come and live with us!’ My wife and I are thinking of setting up a Maharishi office and charging fifty dollars for a couple of minutes of chat.”

The most serious criticism of Star Wars on its initial release was that it embodies Nazi mythology, and several critics noted that the film’s closing victory ceremony was inspired by Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph Of The Will (1935). Was the mystical ‘Force’ which figures so prominently in the film, and provides Luke with the power to destroy the Death Star, an expression of basic Nazi beliefs? Absurdly far-fetched though this may be, the film did reflect a growing tendency among the young to reject rationalism in favour of mysticism. Kenobi instructs Luke saying, “Your eyes can deceive you, don’t trust them. Stretch out with your feelings. Let go of your conscious self and act on instinct.” Sir Alec Guinness, who played Kenobi, was concerned that some people were taking his mystical pronouncements seriously. “I’ve been getting some strange letters from America, from married couples, not teenagers. They think that because I play a wise man in the film I can solve all their problems. The letters say, ‘You’ve altered our lives, you must come and live with us!’ My wife and I are thinking of setting up a Maharishi office and charging fifty dollars for a couple of minutes of chat.”

Though George claims that it’s a purely ‘fun’ movie aimed at providing children with a rich fantasy life of the sort George had when he was young, Star Wars is possibly the most violent movie of all-time. It’s one long battle, beginning with a massacre on board a spaceship and ending in an orgy of futuristic destruction, while along the way an entire planet and its population are blasted into oblivion. All-in-all Star Wars racks up a higher body-count than World War Two and Vietnam put together. There’s not much blood, of course, and no-one actually suffers onscreen, so that makes it good, harmless, clean fun.

Though George claims that it’s a purely ‘fun’ movie aimed at providing children with a rich fantasy life of the sort George had when he was young, Star Wars is possibly the most violent movie of all-time. It’s one long battle, beginning with a massacre on board a spaceship and ending in an orgy of futuristic destruction, while along the way an entire planet and its population are blasted into oblivion. All-in-all Star Wars racks up a higher body-count than World War Two and Vietnam put together. There’s not much blood, of course, and no-one actually suffers onscreen, so that makes it good, harmless, clean fun.

Leaving aside these petty objections, there is no doubt that George had put the nearest thing to real ‘space opera’ on the screen at last. Thanks to his familiarity with the traditions of science fiction, Star Wars is filled with the visual realisation of things that had previously only existed in the imaginations of science fiction authors and their readers, like the scene in which a faster-than-light ship called the Millennium Falcon enters hyperspace to escape imperial cruisers. The special effects, especially the model work, is almost above criticism. For the first time since 2001: A Space Odyssey models were used impressively and photographed properly. All the space vehicles have a feeling of size, and the Death Star itself appears to have the dimensions of a moon. Apart from the occasional matte line, the only real criticism of the original print of Star Wars concerns the sequences where the planet Alderaan is blown up, and later the Death Star is destroyed. In both cases the explosions occur much too quickly and therefore fail to convey the hugeness of the object being exploded. George himself was never completely satisfied with the effects:

Leaving aside these petty objections, there is no doubt that George had put the nearest thing to real ‘space opera’ on the screen at last. Thanks to his familiarity with the traditions of science fiction, Star Wars is filled with the visual realisation of things that had previously only existed in the imaginations of science fiction authors and their readers, like the scene in which a faster-than-light ship called the Millennium Falcon enters hyperspace to escape imperial cruisers. The special effects, especially the model work, is almost above criticism. For the first time since 2001: A Space Odyssey models were used impressively and photographed properly. All the space vehicles have a feeling of size, and the Death Star itself appears to have the dimensions of a moon. Apart from the occasional matte line, the only real criticism of the original print of Star Wars concerns the sequences where the planet Alderaan is blown up, and later the Death Star is destroyed. In both cases the explosions occur much too quickly and therefore fail to convey the hugeness of the object being exploded. George himself was never completely satisfied with the effects:

“On a technical level it can be compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but personally I think 2001 is far superior. 2001 had more time and money put into it and obviously it came out better. Most of the special effects in Star Wars were first-time special effects – we shot them, we composited them and they’re in the movie. We had to go back and reshoot some but, because of the cost, much of our stuff we had to do as a one-shot deal. We did a lot of work but there is nothing that I would like to do more than go back and redo all the special effects.” When the film was rereleased prior to Star Wars V The Empire Strikes Back (1980), George added the now-established ‘Episode IV A New Hope‘ subtitle at the beginning of the scroll, though this was not present in the original release. He has since tweaked the film on a further three occasions, primarily to update the effects, but to also add a previously deleted scene with Jabba The Hutt, and to make Han Solo less of a ruthless gunslinger by shooting Greedo in self-defence.

“On a technical level it can be compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but personally I think 2001 is far superior. 2001 had more time and money put into it and obviously it came out better. Most of the special effects in Star Wars were first-time special effects – we shot them, we composited them and they’re in the movie. We had to go back and reshoot some but, because of the cost, much of our stuff we had to do as a one-shot deal. We did a lot of work but there is nothing that I would like to do more than go back and redo all the special effects.” When the film was rereleased prior to Star Wars V The Empire Strikes Back (1980), George added the now-established ‘Episode IV A New Hope‘ subtitle at the beginning of the scroll, though this was not present in the original release. He has since tweaked the film on a further three occasions, primarily to update the effects, but to also add a previously deleted scene with Jabba The Hutt, and to make Han Solo less of a ruthless gunslinger by shooting Greedo in self-defence.

But no amount of clunky dialogue or effects or continuity-tinkering can detract from the sheer spectacle and ‘Wow!’ moments of a film that forever changed the shape of cinema. George had been working on the Star Wars script for several years. It began life as a planned sequel to THX 1138 (1971), but it wasn’t until after making the successful American Graffiti (1973) that he began trying to launch the project in earnest. With producer Gary Kurtz he approached big Hollywood companies like United Artists and Universal but was repeatedly disappointed. He finally talked 20th Century Fox into becoming involved, mainly because of their previous success with the Planet Of The Apes (1968) franchise. At this point Star Wars began its long and complicated journey from the page to the screen.

But no amount of clunky dialogue or effects or continuity-tinkering can detract from the sheer spectacle and ‘Wow!’ moments of a film that forever changed the shape of cinema. George had been working on the Star Wars script for several years. It began life as a planned sequel to THX 1138 (1971), but it wasn’t until after making the successful American Graffiti (1973) that he began trying to launch the project in earnest. With producer Gary Kurtz he approached big Hollywood companies like United Artists and Universal but was repeatedly disappointed. He finally talked 20th Century Fox into becoming involved, mainly because of their previous success with the Planet Of The Apes (1968) franchise. At this point Star Wars began its long and complicated journey from the page to the screen.

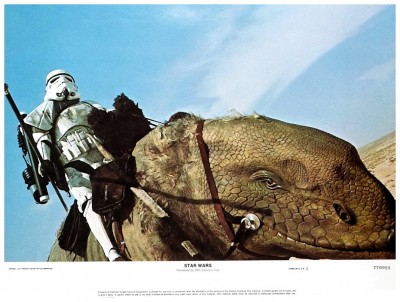

One of the first tasks was to find suitable locations. Originally it had been planned to make Luke Skywalker’s home world a jungle planet and therefore the jungles of the Philippines were considered a possibility, but it was decided that shooting for months in a jungle would present too many problems – as Francis Ford Coppola would later find out while making Apocalypse Now (1979) – so Tatooine suddenly became a desert world. The deserts of Tunisia were chosen for the location sequences and, in March 1976, the Star Wars cast and crew descended upon the small town of Tozeur. The construction crew worked for eight weeks to turn the desert and town into another planet, aided by the alien landscape where, due to the many mirages, it was already difficult to separate the real from the unreal.

One of the first tasks was to find suitable locations. Originally it had been planned to make Luke Skywalker’s home world a jungle planet and therefore the jungles of the Philippines were considered a possibility, but it was decided that shooting for months in a jungle would present too many problems – as Francis Ford Coppola would later find out while making Apocalypse Now (1979) – so Tatooine suddenly became a desert world. The deserts of Tunisia were chosen for the location sequences and, in March 1976, the Star Wars cast and crew descended upon the small town of Tozeur. The construction crew worked for eight weeks to turn the desert and town into another planet, aided by the alien landscape where, due to the many mirages, it was already difficult to separate the real from the unreal.

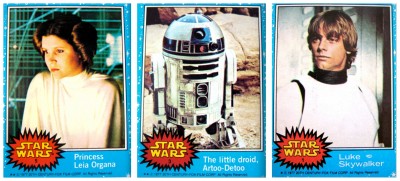

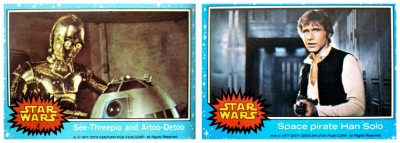

The cast of Star Wars, like the technical team, was a mixture of American and British artists. Young American television actor Mark Hamill made his feature film debut as the hero Luke Skywalker. Han Solo was played by Harrison Ford, who had a role in George’s previous film, American Graffiti, as well as appearing in Apocalypse Now, a project that George and his then-wife Marcia Lucas were involved in for quite some time before Star Wars. Princess Leia Organa was played by Carrie Fisher, daughter of actors Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher. The British contingent consisted of Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin, Kenny Baker and Anthony Daniels as the two robots Artoo and Threepio, and Peter Mayhew (a former London hospital worker) as the towering Wookiee named Chewbacca. The villainous Lord Darth Vader consisted of two people, one British and one American. Filling his black costume and evil-looking mask was David Prowse, a six-foot seven-inch tall weightlifter who, apart from appearing as Frankenstein’s monster in at least two films and performing villainous roles in such films as A Clockwork Orange (1971), Jabberwocky (1977) and The People That Time Forgot (1977), also ran a gymnasium in London, while Darth Vader’s deep magnetic voice was provided by James Earl Jones. The most prestigious British actor in the film was Sir Alec Guinness who plays Kenobi, last of the Jedi Knights. He was not terribly enthusiastic about the idea at first:

The cast of Star Wars, like the technical team, was a mixture of American and British artists. Young American television actor Mark Hamill made his feature film debut as the hero Luke Skywalker. Han Solo was played by Harrison Ford, who had a role in George’s previous film, American Graffiti, as well as appearing in Apocalypse Now, a project that George and his then-wife Marcia Lucas were involved in for quite some time before Star Wars. Princess Leia Organa was played by Carrie Fisher, daughter of actors Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher. The British contingent consisted of Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin, Kenny Baker and Anthony Daniels as the two robots Artoo and Threepio, and Peter Mayhew (a former London hospital worker) as the towering Wookiee named Chewbacca. The villainous Lord Darth Vader consisted of two people, one British and one American. Filling his black costume and evil-looking mask was David Prowse, a six-foot seven-inch tall weightlifter who, apart from appearing as Frankenstein’s monster in at least two films and performing villainous roles in such films as A Clockwork Orange (1971), Jabberwocky (1977) and The People That Time Forgot (1977), also ran a gymnasium in London, while Darth Vader’s deep magnetic voice was provided by James Earl Jones. The most prestigious British actor in the film was Sir Alec Guinness who plays Kenobi, last of the Jedi Knights. He was not terribly enthusiastic about the idea at first:

“The script came through the door and the moment I saw the sci-fi sticker on it I said to myself, ‘Oh crumbs, it’s not for me,’ but then I started to read and I had to turn the page – it had vigour and I finished it at a single sitting. I found the script curious in places and I didn’t understand it all, but I was held by a certain excitement, a perfectly ordinary straightforward excitement. I hadn’t met Lucas previously so I went off and saw his American Graffiti, which I found impressive. Soon after that we came together and he struck me as being a very considerable little person, by that I mean small in stature. In many ways he is quite untypical of the film industry. When we started to work on Star Wars it was all so calm, so gentlemanly. No fat cigars, no tough language. I remember someone on the set criticising Lucas because of his lack of display and announcing that the film was going to be dull. So I took him aside and said, ‘Mark my words, this film is going to have distinction’.” On that rather upbeat note I’d like to profusely thank Time magazine (30th May 1977), The Evening Standard (29th September 1977), The Times (December 1977), and Rolling Stone magazine (#246) for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to please join me next week so I can poke you in the eye with another frightful excursion to the backside of Hollywood, filmed in gloriously grainy 2-D black & white Regularscope for…Horror News! Toodles!

“The script came through the door and the moment I saw the sci-fi sticker on it I said to myself, ‘Oh crumbs, it’s not for me,’ but then I started to read and I had to turn the page – it had vigour and I finished it at a single sitting. I found the script curious in places and I didn’t understand it all, but I was held by a certain excitement, a perfectly ordinary straightforward excitement. I hadn’t met Lucas previously so I went off and saw his American Graffiti, which I found impressive. Soon after that we came together and he struck me as being a very considerable little person, by that I mean small in stature. In many ways he is quite untypical of the film industry. When we started to work on Star Wars it was all so calm, so gentlemanly. No fat cigars, no tough language. I remember someone on the set criticising Lucas because of his lack of display and announcing that the film was going to be dull. So I took him aside and said, ‘Mark my words, this film is going to have distinction’.” On that rather upbeat note I’d like to profusely thank Time magazine (30th May 1977), The Evening Standard (29th September 1977), The Times (December 1977), and Rolling Stone magazine (#246) for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to please join me next week so I can poke you in the eye with another frightful excursion to the backside of Hollywood, filmed in gloriously grainy 2-D black & white Regularscope for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews