There were some good but usually fairly conventional fantasies produced by the commercial cinema in the forties. But in the middle of all this was one small oasis of the unusual: The low-budget low-key horror movies produced by Val Lewton for RKO Radio Pictures between 1942 and 1945, and made by a small, fairly autonomous unit, saving money where possible by using little-known contract actors and already existing studio sets.

There were some good but usually fairly conventional fantasies produced by the commercial cinema in the forties. But in the middle of all this was one small oasis of the unusual: The low-budget low-key horror movies produced by Val Lewton for RKO Radio Pictures between 1942 and 1945, and made by a small, fairly autonomous unit, saving money where possible by using little-known contract actors and already existing studio sets.

Val Lewton worked with three directors on these films – Jacques Tourneur on Cat People (1942), I Walked With A Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943) – Mark Robson on The Seventh Victim (1943), The Ghost Ship (1943), Isle Of The Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946) – Robert Wise on Curse Of The Cat People (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1946). Though all of them have their uncanny moments, four of the films aren’t fantasy at all – The Leopard Man, The Ghost Ship, The Body Snatcher and Bedlam. The remainder operate a little precariously on the ambiguous borderline between true fantasy and psychological melodrama. Today I wish to discuss the work of Jacques Tourneur, who was arguably the most successful of the three directors in imprinting his own personality on films that were essentially designed by an intelligent committee.

Val Lewton worked with three directors on these films – Jacques Tourneur on Cat People (1942), I Walked With A Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943) – Mark Robson on The Seventh Victim (1943), The Ghost Ship (1943), Isle Of The Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946) – Robert Wise on Curse Of The Cat People (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1946). Though all of them have their uncanny moments, four of the films aren’t fantasy at all – The Leopard Man, The Ghost Ship, The Body Snatcher and Bedlam. The remainder operate a little precariously on the ambiguous borderline between true fantasy and psychological melodrama. Today I wish to discuss the work of Jacques Tourneur, who was arguably the most successful of the three directors in imprinting his own personality on films that were essentially designed by an intelligent committee.

The first point to note about all nine Val Lewton productions, including those directed by Jacques, is that they reinforce the pattern already outlined in forties fantasy: Good taste, restraint, and a certain staginess. The creature movies from Universal were the exception to this pattern, and were a little more direct – The Wolf Man (1941) reveals its rather slender horrors almost face-on. But for all the praise that has been lavished on Val’s films for their tactfulness, it is not for this reason they are remembered. Rather, it is a kind of breathless, claustrophobic, shadowy quality, a sense of impotence in the face of ill-defined menaces that may be purely subjective, but which nevertheless create a neurotic, high-strung tension, and finally even terror.

The first point to note about all nine Val Lewton productions, including those directed by Jacques, is that they reinforce the pattern already outlined in forties fantasy: Good taste, restraint, and a certain staginess. The creature movies from Universal were the exception to this pattern, and were a little more direct – The Wolf Man (1941) reveals its rather slender horrors almost face-on. But for all the praise that has been lavished on Val’s films for their tactfulness, it is not for this reason they are remembered. Rather, it is a kind of breathless, claustrophobic, shadowy quality, a sense of impotence in the face of ill-defined menaces that may be purely subjective, but which nevertheless create a neurotic, high-strung tension, and finally even terror.

Cat People, photographed like many of the best Val Lewton films, in a highly-wrought style of chiaroscuro – lots of shadows and highlights – by Nicholas Musuraca, tells of a woman fashion designer (Simone Simon) with a Serbian background, who fears that she may be a were-cat. She falls in love and marries, but will not give herself sexually to her husband because the orgasmic release may bring about her transformation into a beast, a panther creature. The sexual element is hinted at, rather than explained in so many words. She goes to see a psychiatrist, who seems to understand her nature. Meanwhile, her husband is attracted to another woman. The other woman is menaced (though not actually hurt) by a half-glimpsed panther. The psychiatrist, attempting to seduce the wife, is attacked by a cat-creature and wounds it with his sword-stick before he dies of his injuries. The film ends with Irena, the wife, releasing a panther from the zoo – which is immediately hit by a car – followed by Irena’s death.

Cat People, photographed like many of the best Val Lewton films, in a highly-wrought style of chiaroscuro – lots of shadows and highlights – by Nicholas Musuraca, tells of a woman fashion designer (Simone Simon) with a Serbian background, who fears that she may be a were-cat. She falls in love and marries, but will not give herself sexually to her husband because the orgasmic release may bring about her transformation into a beast, a panther creature. The sexual element is hinted at, rather than explained in so many words. She goes to see a psychiatrist, who seems to understand her nature. Meanwhile, her husband is attracted to another woman. The other woman is menaced (though not actually hurt) by a half-glimpsed panther. The psychiatrist, attempting to seduce the wife, is attacked by a cat-creature and wounds it with his sword-stick before he dies of his injuries. The film ends with Irena, the wife, releasing a panther from the zoo – which is immediately hit by a car – followed by Irena’s death.

Fundamentally, all this is the lurid romanticism of a story from a pulp-magazine like Weird Tales, but much has been done (the use of a painting by Goya and a poem by John Donne) to make it ‘artistic’. The strength of the film lies in its symbolic representation of sexual repression, though the Freudian elements are a little too obtrusive, with phallic symbols like sword-canes and keys protruding randomly whenever Irena is around. Also, Tourneur is a masterful creator of atmosphere, most notably in the scene where Alice (the other woman) is swimming in a deserted indoor pool and suddenly feels menaced (her robe is torn to shreds, apparently by claws), and the scene where again she senses herself being followed while walking through the park at night – a careful build-up of tension ends in what sounds to be the hiss of an attacking cat, but it is only the air-brakes of an approaching bus, on which she makes her escape.

Fundamentally, all this is the lurid romanticism of a story from a pulp-magazine like Weird Tales, but much has been done (the use of a painting by Goya and a poem by John Donne) to make it ‘artistic’. The strength of the film lies in its symbolic representation of sexual repression, though the Freudian elements are a little too obtrusive, with phallic symbols like sword-canes and keys protruding randomly whenever Irena is around. Also, Tourneur is a masterful creator of atmosphere, most notably in the scene where Alice (the other woman) is swimming in a deserted indoor pool and suddenly feels menaced (her robe is torn to shreds, apparently by claws), and the scene where again she senses herself being followed while walking through the park at night – a careful build-up of tension ends in what sounds to be the hiss of an attacking cat, but it is only the air-brakes of an approaching bus, on which she makes her escape.

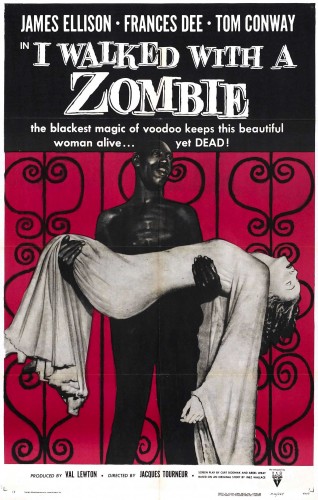

Like Cat People, I Walked With A Zombie implies a supernatural explanation for events, but allows the psychological explanation as a let-out for rationalist audiences. The film has one of the several deceptively garish titles imposed on Val Lewton by RKO (he delighted in finding literate solutions to the quandaries such coarse titles placed him in). In fact I Walked With A Zombie is delicate, almost insubstantial in its evocation of eeriness. The story, which is consciously modeled on Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, tells of a nurse hired to care for the trance-like wife of a plantation owner in Haiti. The black islanders believe she is a zombie, a member of the living dead, and the film’s most extraordinarily atmospheric sequence shows the nurse and the somnambulistic wife walking at night through rustling cane-fields, past hanging voodoo symbols, to seek help from the local witch-doctor who, in an about-turn of amazing implausibility, turns out to be the wife’s mother-in-law. She has been feeding the superstitious fears of the natives as a way of persuading them to accept orthodox medical treatments!

Like Cat People, I Walked With A Zombie implies a supernatural explanation for events, but allows the psychological explanation as a let-out for rationalist audiences. The film has one of the several deceptively garish titles imposed on Val Lewton by RKO (he delighted in finding literate solutions to the quandaries such coarse titles placed him in). In fact I Walked With A Zombie is delicate, almost insubstantial in its evocation of eeriness. The story, which is consciously modeled on Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, tells of a nurse hired to care for the trance-like wife of a plantation owner in Haiti. The black islanders believe she is a zombie, a member of the living dead, and the film’s most extraordinarily atmospheric sequence shows the nurse and the somnambulistic wife walking at night through rustling cane-fields, past hanging voodoo symbols, to seek help from the local witch-doctor who, in an about-turn of amazing implausibility, turns out to be the wife’s mother-in-law. She has been feeding the superstitious fears of the natives as a way of persuading them to accept orthodox medical treatments!

The film uses its many black actors with a dignity unusual for the time. Darby Jones is compelling as the tall, sombre zombie – not at all a creature to be pitied – who looms up before the white-gowned women as they drift through the sugar-cane. He watches again, as the wife is carried into the sea at the end, having been killed by the drunken brother-in-law who loves her. He seems to be an immobile symbol of a way of being that is ultimately untouched by the melodramatic goings-on of a white world that has only briefly and accidentally brushed against his. It is never established whether or not the wife is genuinely a victim of voodoo, or merely insane. More important perhaps is the subtext established by the strongly conflicting images of the film – an ethereal death-like whiteness on the one hand, and the pulsing voodoo drums on the other, which seem to stand for a life of sexual repression versus a life of sexual warmth.

The film uses its many black actors with a dignity unusual for the time. Darby Jones is compelling as the tall, sombre zombie – not at all a creature to be pitied – who looms up before the white-gowned women as they drift through the sugar-cane. He watches again, as the wife is carried into the sea at the end, having been killed by the drunken brother-in-law who loves her. He seems to be an immobile symbol of a way of being that is ultimately untouched by the melodramatic goings-on of a white world that has only briefly and accidentally brushed against his. It is never established whether or not the wife is genuinely a victim of voodoo, or merely insane. More important perhaps is the subtext established by the strongly conflicting images of the film – an ethereal death-like whiteness on the one hand, and the pulsing voodoo drums on the other, which seem to stand for a life of sexual repression versus a life of sexual warmth.

The Val Lewton films have been technically influential in showing how a fantastic atmosphere can be created with minimal resources. Possible, however, they have been still more influential in their linking of fantastic mythologies to the equally superstitious iconography of post-Freudianism. These dark mysteries, flickering at the nervous edges of our everyday vision, come to reflect a turmoil within the human mind. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

The Val Lewton films have been technically influential in showing how a fantastic atmosphere can be created with minimal resources. Possible, however, they have been still more influential in their linking of fantastic mythologies to the equally superstitious iconography of post-Freudianism. These dark mysteries, flickering at the nervous edges of our everyday vision, come to reflect a turmoil within the human mind. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews