Horror News is mostly devoted to horror as a definable separate genre, that is, to films that draw upon (and occasionally expand) an existing tradition. Most of the directors and writers who work in this field are very conscious of belonging to a generic tradition.

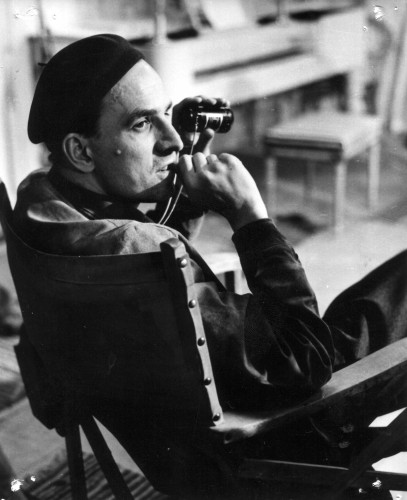

Horror News is mostly devoted to horror as a definable separate genre, that is, to films that draw upon (and occasionally expand) an existing tradition. Most of the directors and writers who work in this field are very conscious of belonging to a generic tradition.  But fantasies and nightmares can be created by anybody, and it sometimes happens that directors from quite different traditions find it appropriate to draw upon the world’s fund of fantastic imagery – not just from films, but from books and poems and paintings – for non-generic uses of their own. Such a director is Ingmar Bergman, who uses a great deal of visionary and horrific imagery in his films, much of which is taken directly from literature, art and myth. Most of Bergman’s film’s could be defined as marginal fantasy, but I have restricted the choice to just six.

But fantasies and nightmares can be created by anybody, and it sometimes happens that directors from quite different traditions find it appropriate to draw upon the world’s fund of fantastic imagery – not just from films, but from books and poems and paintings – for non-generic uses of their own. Such a director is Ingmar Bergman, who uses a great deal of visionary and horrific imagery in his films, much of which is taken directly from literature, art and myth. Most of Bergman’s film’s could be defined as marginal fantasy, but I have restricted the choice to just six.

The Seventh Seal (1957) is an allegory, beautifully photographed in black-and-white by Gunnar Fischer. Max Von Sydow is the Knight, riding with his sardonic squire across the ravaged landscape of Europe in the Dark Ages, a world suffering from plague and anarchy during the time of the Crusades. Early in the morning he meets the figure of Death on the beach. Later the Knight confesses in church but it is Death who hears him (and points out that God may not be there to hear his prayers – a viewpoint that seems all too possible when we see the squalor and misery through which the Knight travels).

He meets Death again at the end, but tries to refuse (with a dignity that seems almost crazy in the circumstances) to submit to the inevitable. The film ends with the Knight and his lady, along with others, capering behind the cowled skeleton in the grotesque (yet not altogether joyless) Dance Of Death.

Priests become rapists, witches are burned, torment is everywhere, only an innocent troupe of actors remains relatively unscathed. Bergman has weighted the scales in this thesis film, whose subject is belief in God and the difficulties of reconciling such a belief with human suffering. Its beautifully composed (if rather studied) scenes are visually very striking, and often echo old paintings and engravings. The Seventh Seal’s imagery added much to the visual iconography of horror cinema.

The Face (aka The Magician 1958) may not strictly be fantasy but, in terms of atmosphere, one of the most fantastic-seeming films ever made. Vogler (Max Von Sydow) is a mesmerising showman, who is both a pseudo-scientific fraud and a genuine magician. Creators may be illusionists and partially corrupt – faces may be masks – can the inexplicable be explained? In brilliant imagery the film confronts the artistic imagination with science, fantasy and reality with some wonderfully Gothic moments.

The Face (aka The Magician 1958) may not strictly be fantasy but, in terms of atmosphere, one of the most fantastic-seeming films ever made. Vogler (Max Von Sydow) is a mesmerising showman, who is both a pseudo-scientific fraud and a genuine magician. Creators may be illusionists and partially corrupt – faces may be masks – can the inexplicable be explained? In brilliant imagery the film confronts the artistic imagination with science, fantasy and reality with some wonderfully Gothic moments.

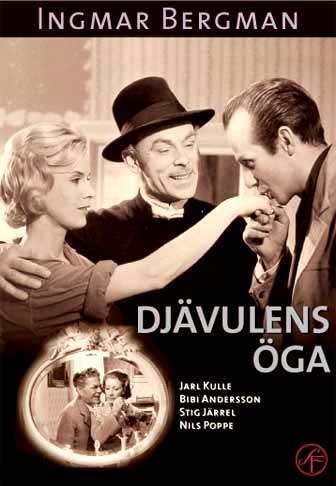

The Devil’s Eye (1960) may be weak for a Bergman film, but it’s still pretty damn good compared to most of its contemporaries. The Devil sends Don Juan to seduce the virgin daughter of a pastor, whose chastity is offensive to Hell.

The Devil’s Eye (1960) may be weak for a Bergman film, but it’s still pretty damn good compared to most of its contemporaries. The Devil sends Don Juan to seduce the virgin daughter of a pastor, whose chastity is offensive to Hell.

The pastor’s wife is attended to by Don Juan’s manservant with rather more success. An engaging light comedy with scenes that take place in Hell, but Bergman’s more serious Hells are far better than this.

The same year Bergman immediately went on his next film, The Virgin Spring (1960), which also added much to the visual iconography of horror cinema, so much so it was even unofficially remade as one of the most brutally sadistic exploitation movies of the seventies, Wes Craven’s Last House On The Left (1972).

The Virgin Spring is based on a medieval ballad which tells of a young fresh girl raped and murdered, and the violent vengeance taken by her father. After the revenge a spring gushes forth from the spot where she died.

There are minor fantastic elements throughout, for the film is set in a period poised between belief in pagan gods such as Odin and a belief in Christianity. The film’s visual symbolism gives a kind of credence to both faiths in images of telling simplicity. The film vividly evokes an age when the natural and the supernatural worlds – the visible and the invisible – seemed more adjacent than they do now.

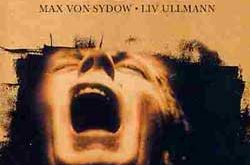

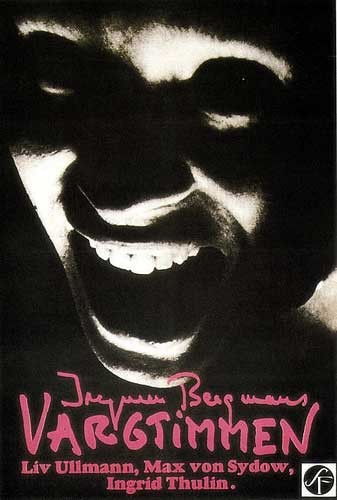

Hour Of The Wolf (1968) tells of painter Johan (Max Von Sydow) and his wife Alma (Liv Ullmann) arriving on a lonely island for a holiday. He feels that his creativity is fading and is tormented by internal demons which, as the film progresses, begins to take external shape. Using character names borrowed from Gothic writer E.T.A. Hoffman and using visual imagery which owes a great deal to the b-movie traditions of horror cinema, Bergman builds to a climax in which Johan enters a castle and attends a nightmare dinner party, where he is attacked both verbally and physically by Gothic manifestations of his own despair.

Among the we have a bird-man, an old woman who peels her face off to reveal the skull beneath, and his ex-lover Veronica, now a member of the living dead. He couples with her to the jeers of demons in the mud and the darkness. All of this takes during the ‘Hour Of The Wolf’, that hour of night when the psyche is at its weakest. Johan’s final descent into a pit of abnormality from which there is no apparent escape is rather cruelly depicted.

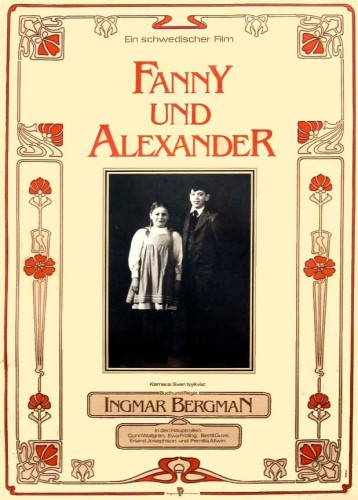

The story of Fanny And Alexander (1982) is set in 1907 Sweden and deals with a young boy named Alexander, his sister Fanny, and their well-to-do family, the Ekdahl’s. The children’s parents are both involved in theatre and are happily married until the father’s sudden death. Shortly thereafter, mother Emilie finds a new suitor in the local bishop, a handsome widower, and accepts his proposal of marriage, moving into his ascetic home and putting the children under his stern and unforgiving rule.

He is particularly hard on Alexander, trying to break his will by every means. The children and their mother live as virtual prisoners in the bishop’s house until finally the Ekdahl family intervenes. With help from an old friend, a Jewish antiques dealer, as well as some magic, the children are smuggled out of the house, but the Ekdahl’s attempts to bribe or threaten the bishop into divorce fail. Emilie, by now pregnant, slips her husband a sedative and flees as he sleeps, after which a fire breaks out and the bishop is burnt to death. In the meantime, Alexander has met the Jewish merchant’s mysterious nephew, and fantasised about his stepfather’s death – it’s as if Alexander’s fantasy comes true as he dreams it.

His final film as director, Fanny And Alexander is directly concerned with what Ingmar Bergman is all about: The illusion of miracles being real, and the possibility that in one way they are just as real as our everyday lives, which are themselves subject to all the illusions of perception. We see what we want to see. Anyway, please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the Public Domain for Horror News. Toodles!

His final film as director, Fanny And Alexander is directly concerned with what Ingmar Bergman is all about: The illusion of miracles being real, and the possibility that in one way they are just as real as our everyday lives, which are themselves subject to all the illusions of perception. We see what we want to see. Anyway, please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the Public Domain for Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews