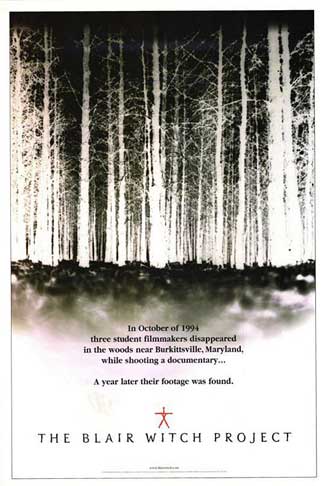

When filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez wrote and directed The Blair Witch Project which debuted in theaters ten years ago this past summer, they ushered in a sub-genre of filmmaking that was part reliant on the power of suggestion, part pre-reality TV, and part old-fashioned exploitation fright film.

Certainly, Blair Witch was a phenomenon in 1999, coming right at the end of perhaps the most pioneering decade in American independent filmmaking, due at least somewhat to inventive Internet marketing, as the web had just recently blossomed at that time. In essence, the filmmakers took three unknown actors and went into the woods on the East Coast with a camcorder and digital audio tape deck and a rough outline of the various events. Due to their inexpensive basic production, ostensibly, much video footage was shot on location, with a coherent movie being cobbled together subsequently in post. But, inarguably, the sum was greater than the spare parts, which individually provided few genuinely frightening moments. With virtually no tricks such as visual effects, visible monsters, creepy soundtrack, or “shock” moments, Blair Witch captured the verisimilitude of being lost in the middle of nowhere whilst being pursued by a legendary but seemingly real supernatural force. Like the glory days of radio, it was what audiences didn’t see that scared them most. Compared to a “horror” movie of that same year with all of the budgetary and production values that a studio feature can offer – the remake of The Haunting – Blair Witch provided vastly more numerous chilling moments that were so real to the audience because they seemed so viscerally real to the no-name performers, who could have been any of the people watching them in the theater.

An unfortunate sequel to the film did not involve either Myrick or Sanchez beyond their basic outline, and both oddly faded into obscurity through the current decade. It was as if their magic was past being duplicated lest it become cliché or parody or worse. But formulas are a strange breed, especially in feature filmmaking as they seem to come and go. And sometimes they come back.

Enter filmmaker Oren Peli. Taking his cue from the spirit of Blair Witch, he conjured a story in which two actors (with two supporting players – Blair Witch had several supporting players in its opening fourth) locked down in one location would encounter all manner of unexplained phenomena and capture the material, in true Blair Witch fashion, on a video camcorder. Like Blair Witch, the camcorder feature makes for both a very conveniently simplistic inexpensive project, but provides stylistic choices that put the audience in an objective scenario right along with the film’s lead characters. Called Paranormal Activity, Peli’s film, taking place all in one house with no exteriors, allows for a claustrophobic feeling, much like Blair Witch’s expansive but ultimately shuttered entrappings of a forest, in which the three leads are imprisoned. Certainly, Paranormal’s characters can leave at any moment, though they are told that it ultimately will not matter, as the titular activity will follow them regardless of their location.

In Peli’s film, as in Myrick/Sanchez’ film, 100% of the activity we see is from “found” footage culled together after the events onscreen have taken place. But though there is editing, it is selective. We are introduced to the people in both worlds, who are merely curious about the phenomena taking place around them as we meet them. In fact, both films feature characters who clearly have disrespect for the supernatural undertakings in their environs, and casually challenge the phenomena by attempting to point a camera at it and otherwise not take it seriously. In fact, in both films, the leads are warned by “experts” in the field not to tempt or otherwise interfere with the phenomena but are ultimately ignored due to the leads’ arrogance or other disregard for that which they are trying to document.

Certainly, the past 30 years have been an age where Americans are eager to point their video cameras at every which thing, and these two films present a cautionary tale about doing so. Just as Blair Witch’s videographer woman never ceases operations, even after threats and violence occurs, so does Paranormal’s fiancé character. One major difference in the two is that while the protagonists in Blair Witch invade territory in which they clearly do not belong, only one of Paranormal’s leads meddles in the affairs of the unknown forces. In the latter case, the unnamed entity has been pursuing the lead female character since birth, for no likely reason that can be explained in human terms.

Various particular warnings/clues fall at the feet of the heroes in both movies. Strange pagan sculptures hang from the trees and are left outside of the tent of Blair Witch’s innocents while long missing photos and etched names of dead previously haunted persons are unearthed in Paranormal’s plot. The daytime is generally harmless in both films despite their respective warnings which are visible during daylight only.

But the night is to be intensely feared in both films. Not only do powerful forces enter the worlds in both, but people are capable of being moved or captured in each film, always by off-screen or invisible beings. We and the characters both know by a certain moment in Blair Witch in which the characters are literally going in circles, that they are being held captive by the supernatural spirits. Likewise, in Paranormal, numerous signs captured on camera, often eerily reached by the hours of footage being fast-forwarded by some off-camera presenter to a dreaded new moment of discovery, give ample warning that the characters are being actively pursued by an invisible often inaudible creature, though we do get periodic physical and auditory evidence of the creature’s existence.

Intelligently, both Myrick/Sanchez and Peli let their stories breathe, setting up their heroes as likeable average people and allowing the information to be revealed slowly and steadily to the audience, one piece at a time, building due tension and terrifically frightening suspense that keeps getting ratcheted to new levels. And both shows rely on selling their material as actual events as really occurred in said footage, having fallen into the hands of police or some authoritarian body who are now showing it to the public. The reality of the camcorder footage is that it always appears to be authentic and represents a genuine clandestine journey on which you endeavor with the characters. This method brings you far closer to the characters than any other possible method of telling this type of story that has previously been explored on film. In fact, you feel as intimate with the leads in each film as is possible for a two-hour experience: until the film plays out, their reality is your reality, and you yearn for characters to heed warnings and be less intrusive with their cameras. But, like freeway drivers who slow down to view an accident, we cannot turn away, though we have been given more than substantial evidence that viewing the upcoming scene will not end well for the characters or us as viewers.

Like Blair Witch, Paranormal is being actively marketed as a film being “demanded” by the viewing public, and such a strategy has reaped due rewards for the distributor. And like its predecessor, with a finale that is both jarring and inexplicable at the same time, again occurring mostly off-camera, Paranormal has a climatic moment in the film which brings all of its inherent clues and ideas to a head. Reportedly, the original shot ending was changed for the film’s wide theatrical release, and both “versions” work well for different reasons. Regardless, a decade later, a model for a stripped-down invasive horror movie again has proved that sometimes much less surface production value can lead to much much more in the eyes and ears of a sophisticated audience.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews