SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Mary Henry is enjoying the day by riding around in a car with two friends. When challenged to a drag, the women accept, but are forced off of a bridge. It appears that all are drowned, until Mary, quite some time later, amazingly emerges from the river. After recovering, Mary accepts a job in a new town as a church organist, only to be dogged by a mysterious phantom figure that seems to reside in an old run-down pavilion. It is here that Mary must confront the personal demons of her spiritual insouciance.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

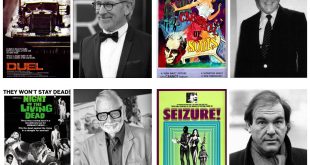

If you look up Sleeper or Cult in any good movie dictionary, you’ll find this week’s subject of discussion. Yes, I have for your bemusement a 1962 chiller that many film fans often mention as one of their own personal discoveries, and an inspiration to generations of low-budget film-makers, Carnival Of Souls (1962).

This creepy cult horror stars Candace Hilligoss, an actress imported from New York, so she already feels alienated. She plays Mary Henry, the lone survivor of the car crash we see in the prologue. Mary goes to Salt Lake City where she has accepted a job as church organist. Where ever she goes, she sees a death-like figure who seems to be pursuing her. She also finds herself being strangely drawn to a deserted dark carnival.

This creepy cult horror stars Candace Hilligoss, an actress imported from New York, so she already feels alienated. She plays Mary Henry, the lone survivor of the car crash we see in the prologue. Mary goes to Salt Lake City where she has accepted a job as church organist. Where ever she goes, she sees a death-like figure who seems to be pursuing her. She also finds herself being strangely drawn to a deserted dark carnival.

The director and lead ghoul Herk Harvey never made another film, making it even more of a cult item. Carnival Of Souls has a lot of clever creepy scenes, like when Mary can’t hear anything, silent and invisible to the people around her, getting on a bus only to find it full of ghouls, witnessing the Dance Of The Dead at the pavilion and of course, the finale.

The director and lead ghoul Herk Harvey never made another film, making it even more of a cult item. Carnival Of Souls has a lot of clever creepy scenes, like when Mary can’t hear anything, silent and invisible to the people around her, getting on a bus only to find it full of ghouls, witnessing the Dance Of The Dead at the pavilion and of course, the finale.

Carnival Of Souls opened in 1962 on a double-bill at a drive-in with The Devil’s Messenger (1962). First-time feature director Herk Harvey, a maker of industrial and educational films, felt confident enough about the film’s viability to leave for South America on a shoot. On his return, his small-time distributor reluctantly gave him a cheque. It bounced. That’s when he knew he was in trouble. Harvey, a college film professor who had such a bad experience with distribution on Carnival Of Souls that he never made another film, and in fact didn’t make any money from it until it’s restored video release a quarter of a century later. In the interim, Carnival Of Souls would not let him rest. Even in the chopped versions that screened on late-night television or the pirated versions that circulated on video, the horror movie became a cult classic.

Carnival Of Souls opened in 1962 on a double-bill at a drive-in with The Devil’s Messenger (1962). First-time feature director Herk Harvey, a maker of industrial and educational films, felt confident enough about the film’s viability to leave for South America on a shoot. On his return, his small-time distributor reluctantly gave him a cheque. It bounced. That’s when he knew he was in trouble. Harvey, a college film professor who had such a bad experience with distribution on Carnival Of Souls that he never made another film, and in fact didn’t make any money from it until it’s restored video release a quarter of a century later. In the interim, Carnival Of Souls would not let him rest. Even in the chopped versions that screened on late-night television or the pirated versions that circulated on video, the horror movie became a cult classic.

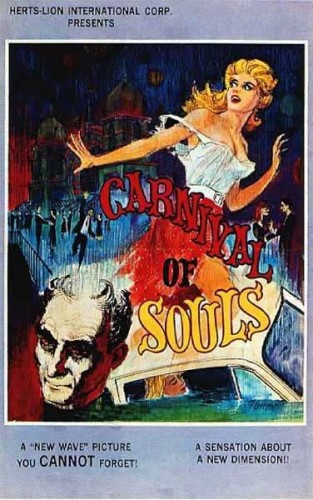

Mostly shot in Herk’s hometown of Lawrence, Kansas for US$30,000, it’s about a lonely church organist, Mary Henry, who survives a car crash into a river on the way to her new job. She emerges dripping from the watery grave where everyone else in the car died, but from then on, reality seems increasingly unreal. She believes she is being pursued by a phantom figure with a chalk-white face and dark circles under his eyes.

Mostly shot in Herk’s hometown of Lawrence, Kansas for US$30,000, it’s about a lonely church organist, Mary Henry, who survives a car crash into a river on the way to her new job. She emerges dripping from the watery grave where everyone else in the car died, but from then on, reality seems increasingly unreal. She believes she is being pursued by a phantom figure with a chalk-white face and dark circles under his eyes.

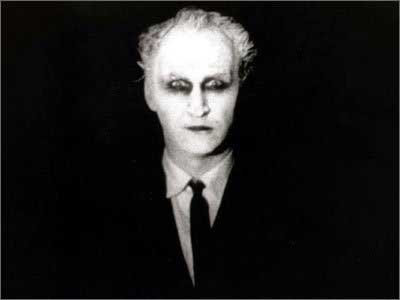

The dark circles may have been justified, since Herk pulled double duty to direct and also play the lead ghoul so as to save money on the measly budget. The make-up he intended to use was egg whites, an elaborate covering that would flake so it looked like it had been in salt water, but due to time and budget restrictions, it finally came down to using regular white greasepaint and darkening the eyes. The organist finds herself less attracted by the holy church she works in, than by a deserted carnival out on the highway. One of the spookiest scenes ever committed to film is the whirling dance of the ghouls in that empty Saltaire pleasure palace.

The dark circles may have been justified, since Herk pulled double duty to direct and also play the lead ghoul so as to save money on the measly budget. The make-up he intended to use was egg whites, an elaborate covering that would flake so it looked like it had been in salt water, but due to time and budget restrictions, it finally came down to using regular white greasepaint and darkening the eyes. The organist finds herself less attracted by the holy church she works in, than by a deserted carnival out on the highway. One of the spookiest scenes ever committed to film is the whirling dance of the ghouls in that empty Saltaire pleasure palace.

Herk was driving back from California one time, and as he went past Salt Lake he saw the pavilion, and couldn’t believe that the old deserted amusement park was there. The lake had receded from it, so it was sitting there on the salt. The state of Utah let him use it for free, and Herk hired students from the university dance troupe to perform the Dance Macabre and the chase scenes, all done in one afternoon. The elegant Saltaire Palace eventually burned down and was completely submerged by the rising water table in the seventies.

Herk was driving back from California one time, and as he went past Salt Lake he saw the pavilion, and couldn’t believe that the old deserted amusement park was there. The lake had receded from it, so it was sitting there on the salt. The state of Utah let him use it for free, and Herk hired students from the university dance troupe to perform the Dance Macabre and the chase scenes, all done in one afternoon. The elegant Saltaire Palace eventually burned down and was completely submerged by the rising water table in the seventies.

One of the ways in which Herk creates the sense of Mary’s dislocation is to film small scenes without any soundtrack. It enhances the metaphor about a single woman’s feeling of isolation in society. When she tries to buy a dress, the sales help ignore her (a common enough experience), and our fears are confirmed by the scenes in which Mary’s therapy sessions are conducted always with the psychiatrist’s back turned. Mary is such a passive, uninvolved, soulless character (she has no religious convictions, no interest in men, no desire for friendship) that she never is really alive, which is why she is unable to recognise her own death.

One of the ways in which Herk creates the sense of Mary’s dislocation is to film small scenes without any soundtrack. It enhances the metaphor about a single woman’s feeling of isolation in society. When she tries to buy a dress, the sales help ignore her (a common enough experience), and our fears are confirmed by the scenes in which Mary’s therapy sessions are conducted always with the psychiatrist’s back turned. Mary is such a passive, uninvolved, soulless character (she has no religious convictions, no interest in men, no desire for friendship) that she never is really alive, which is why she is unable to recognise her own death.

The mood, enhanced by the stark black and white cinematography and the dismal landscape, is one of unrelenting melancholy. The film works not only because it is so economical in its use of character and budget, but also because it plays on common feelings of insignificance and helplessness. Director Herk Harvey and screenwriter John Clifford don’t really seem to blame her for withdrawing from society. Her male neighbour is a lecherous pig, her landlady is a nosy bitch, and her priest employer casts her from the church for playing gloomy music. Even her own doctor makes accusing remarks.

The mood, enhanced by the stark black and white cinematography and the dismal landscape, is one of unrelenting melancholy. The film works not only because it is so economical in its use of character and budget, but also because it plays on common feelings of insignificance and helplessness. Director Herk Harvey and screenwriter John Clifford don’t really seem to blame her for withdrawing from society. Her male neighbour is a lecherous pig, her landlady is a nosy bitch, and her priest employer casts her from the church for playing gloomy music. Even her own doctor makes accusing remarks.

Obvious inspirations beside Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) include The Twilight Zone episodes Death Ship and The Hitchhiker, but remember Carnival Of Souls pre-dates George Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead (1968), the pilot episode of the great Australian anthology series The Evil Touch, and it almost definitely scared the pants off of director M. Night Shyamalan as a child. Maybe the moral of this story is Live While You’re Alive, or Soft Words Butter No Parsnips, or something like that. Anyway, please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Obvious inspirations beside Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) include The Twilight Zone episodes Death Ship and The Hitchhiker, but remember Carnival Of Souls pre-dates George Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead (1968), the pilot episode of the great Australian anthology series The Evil Touch, and it almost definitely scared the pants off of director M. Night Shyamalan as a child. Maybe the moral of this story is Live While You’re Alive, or Soft Words Butter No Parsnips, or something like that. Anyway, please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Carnival Of Souls (1962)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![forsaken[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/forsaken1-310x165.jpg)