The deserved fate of the slasher film cycle seemed ball-and-chained to derivativeness. How many times could audiences sit through the same film with barely different faces? Lack of originality, combined with a lazy approach to filmmaking, won’t lead to decent films. However, an inspired creative team might elevate a conventional into something different. Style and passion count, and a film might come along and say, “It’s not a retread. We’re showing a better way to do things.”

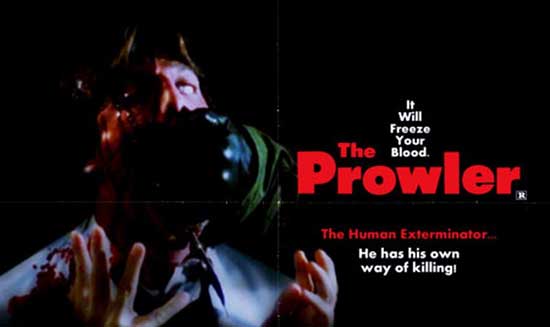

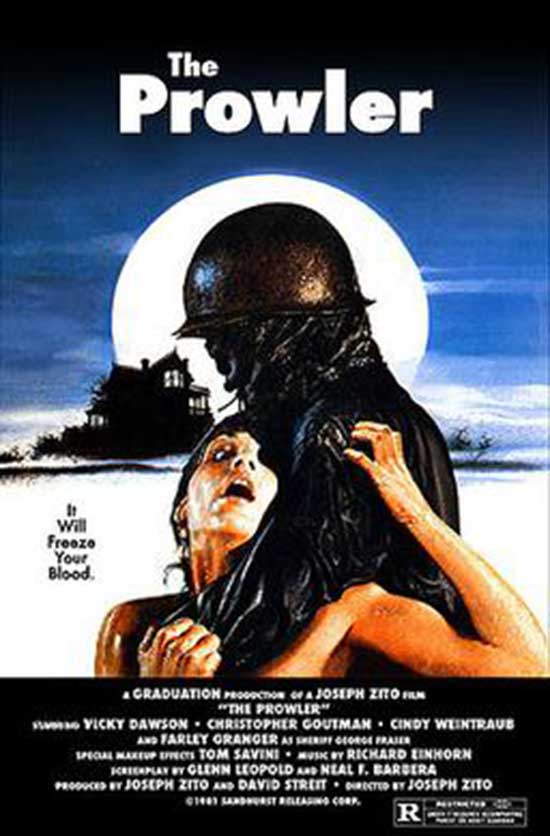

Welcome to The Prowler (1981), a once overlooked horror gem that infused much-needed passion into a subgenre that started to run out of steam after barely starting.

Before way-backing to The Prowler, let’s put the picture, and its titular prowler-slasher, into perspective.

Slash Today, Gone Tomorrow

The slasher cycle died of self-immolation. How many retreads might an audience suffer before it stops showing up in theaters? More than expected, but only for a short time

Encapsulating the history of slasher movies in a short essay proves both impossible and unnecessary. Adam Rockoff’s outstanding book, Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978 – 1986,” delivers the definitive look at the cycle. Some clarifying points about the slasher subgenre bear mentioning here, though.

Stalk-and-slash films were hit-and-miss. Some films scored incredibly well at the box office, while others turned out disappointing. The $250,000-budgeted Graduation Day (1981) lacks the following of My Bloody Valentine (1981), a superior film, but Graduation Day scored big in theaters, with a nearly $24 million take to My Bloody Valentine’s $6 million. Shockingly, Halloween II (1981) only made $25 million, and Graduation Day beat Friday the 13th Part 2’s $21.7 million.

Who needed a studio, a sequel, or a decent budget? Anyone could take a money-making shot with a slasher picture.

During the heydey of 1980 and 1981, a slasher movie had a good chance of making a decent profit along with the potential to score a big hit. The $1.5 million-budgeted and super-silly Prom Night (1980) a popular drive-in film upon its initial release that now enjoys a mild following did “okay” with a $15 million in ticket sales. When looking at the many impressive figures, indie producers and directors saw opportunities. They could make a low-budget film and sell it for a profit to a distributor. The distributor took risks with the acquisition, marketing, and other costs, but the chance to reap huge returns existed.

Some learned about the variances between opportunities and guarantees the hard way. Not every slasher film made money or landed a sweetheart distribution deal. The Prey (1983) sat unreleased for 4 years, hitting screens long after audiences tired of non-franchise slashers. Lots of forgettable films came and went, performing poorly at the box office and deservedly so. Awful, derivative, no-budget films intended to make a quick buck sometimes end up making nothing at all. The slasher cycle’s popularity declined dramatically in 1982, but painfully continued until around 1986.

The highpoint 1980/1981 evenings at the drive-in faded to memory. Lesser-known slasher features wallow in obscurity. Then, someone looks back and rediscovers a rare gem.

The Prowler sat overlooked for a long, long time.

On the Prowl

Sending one of the Greatest Generation a “Dear John” letter while he’s off fighting for the very existence of the free world deserves a one-word description: awful. An even more awful event takes place as summer 1945 approaches when a mysterious figure dressed in trench warfare-like military garb pitchfork-kills the letter writer and her paramour on a school’s graduation dance eve.

Time and many other things changed between 1945 to now (then) 1980, although cinematic political incorrectness still abounds. Change hangs in the air, like dread, in the small town of Avalon Bay. The good people now think it’s now acceptable to restart the graduation dance.

Presentism refers to injecting modern criticisms and sensibilities into less enlightened times. In 1980, Avalon Bay’s townspeople had no idea their actions risked provoking a homicidal slasher to rampage. They didn’t know any better. It was not like it was 1981 or something.

Clueless teens tempt fate, and fate strikes back hard.

Audiences may feel sympathy for the victims, as they only intended to organize a harmless dance. They also put effort into clawing away at sympathy levels.

No matter how annoying or off-putting, mere distaste for someone’s obnoxiousness does not justify harmful action. In an alternate world where annoying and odious behaviors rise to serious crimes, The Prowler’s victims would be doing long prison stretches . My God, these teenagers are vapid, self-centered, annoying, and dislikable. Worst of all, they’re dishonest since all these teenagers are in their 20s.

One-note 20-somethings who never left high school were staples of the slasher subgenre for a reason: teens and 20-somethings bought all those tickets at the drive-ins. They didn’t ask for much, so they didn’t receive much, most of the time.

Prowling Beyond the Lowbrow

The Prowler is not your average slasher film, and its bane and benefit are Tom Savini’s special effects.

Wistful thinking abounded among those thinking The Prowler would pass the MPAA with an R- rating. If Sonny Chiba’s The Street Fighter ended up slapped with an X, what did they expect with this over-the-top slasher? And honestly, the Psycho– inspired” (nee cribbed) misogynistic shower murder did deserve drastic cuts. A point comes when the violence turns an audience off, a self-defeating filmmaking approach.

The Prowler would doubtfully receive many second looks if an uncut print failed to surface. Fans feel intrigued when lost footage turns up. Tom Savini’s realistic gore effects might draw fans to the Blue Underground Blu-ray release, but director Joseph Zito adds several touches that may lead them to appreciate The Prowler as something special.

The score reflects one of those touches.

Using music to heighten suspense sometimes comes off as cheating, but The Prowler weaves in “warning” music at appropriate moments. In scenes where characters believe they are alone, the music has a silent film accompaniment quality. The music shares the audience’s knowledge that something will happen, even though the victim stays lulled into safety.

Soon-to-be final girl Pam can’t hear the music, and she doesn’t know she’s in the same room as The Prowler. And The Prowler does prowl, as the menacing character doesn’t jump out right away. Pam even leaves the room unharmed, walking down the steps until she sees a shadow, The Prowler’s shadow.

The mix of sound and images heighten tension, a vital trait for a decent horror film. Zito’s choice of camera angles, combined with the slower pace, leads to wondering how events play out. Horror films that move too fast hamper tension, although going too slow undermines the genre’s often necessary faster pace. Zito balances the proceedings well, a balancing act not present in lesser films.

When Pam and boyfriend/police deputy Mark search the mysterious Major Chatham’s house, extreme close-ups combined with shadowy interiors add claustrophobia. Assumptions that The Prowler lurks in the shadows lead the audience to think a confrontation looms. Zito sets up his shots effectively, and an eerie art direction hangs over many scenes. Who wouldn’t feel a little on edge when a camera POV peers up from the inside of a grave?

Zito appeared to work harder to overcome the limitations of a pedestrian screenplay, a script by Hanna-Barbera story editor (!) Glenn Leopold and Neal Barbera, Joseph Barbera’s son. A deliberate pace makes flatly-conceived scenes foreboding.

The Prowler prowls. Milking tension by slowing down scenes, well-shot scenes, lets the audience and distributor-demanded weak screenplay conventions remain while adding something more.

And then there’s The Prowler himself.

Prowling About in Early-80’s Horror

A slasher film lives and dies based on its title maniac and final girl. Pam seems capable at escaping, but she’s facing someone capable of murder.

The title Prowler has a great look and, more importantly, a creepy quality. The slow, Michael Myers pace makes him menacing. While The Shape’s deliberate movements hinted at otherworldliness, The Prowler embodies a sick sort of confidence. He’s a tough guy in military gear, intimidating in his cruel actions.

Zito avoids showing too much of The Prowler at once. Medium shots of his torso, close-ups of his boots, and shots made from a distance keep The Prowler hidden even when the murderer reveals himself.

Unfortunately, audiences had to see the film to appreciate Zito’s style, and few people did. The Prowler wasn’t distributed by a big-time studio and marketing materials lacked anything special. The box office returns were about as low a slasher movie could make in those days, reportedly under $1 million at the box office.

The film did help Joe Zito’s career, as he went to helm Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter, along with the Chuck Norris Cannon classics Missing in Action

and Invasion USA.

Epilogue

Why does the film have a Carrie-homage ending? Come up with a creative reason, and you’ll get the answer.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews