SYNOPSIS:

A man sees his life changed forever when his fiancee shoots herself. Baffled, he wants by all means to obtain such a weapon of destruction and he finds himself caught in the middle of a violent group of young vicious punks. They first beat him severely and then he seeks revenge with his fist, then with a gun. Everything from then on is a complete downward spiral.

REVIEW:

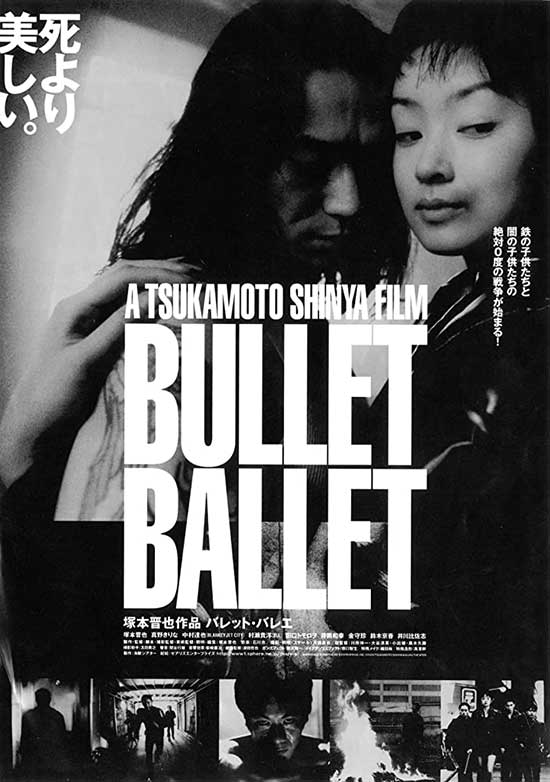

Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s 1998 drama-noir Bullet Ballet is one of the bleakest additions on the master filmmaker’s catalogue. Unlike the title would suggest, it offers very little in a form of gun violence, instead exploring themes of grief, isolation and obsession in Tsukamoto’s trademark style.

TV commercial director Goda’s (Tsukamoto himself) quiet life is thrown out of course when his long-time girlfriend Kiriko (Kyôka Suzuki) suddenly commits suicide by shooting herself. Shocked and traumatised, Goda goes on a desperate mission to find out why this happened, but what starts as a quest to find answers, soon turns into an obsession to get a hold of a firearm of his own. Along the way he meets a young girl named Chisato (Kirina Mano) and a drug dealer Idei (Tatsuya Nakamura) and gets tangled up the bloody conflicts of violent street gangs, spiralling ever further down in a vortex of self-destruction.

I come from, and currently live in a country with fairly strict laws surrounding gun ownership. In my current domicile, UK, automatic and most semi-automatic firearms are completely banned and even the ownership of such guns as hunting rifles is only possible after a thorough background check by the police, part of which is the police inspecting your premises and making sure you have the capacity to store the firearms safely (gun and bullets in separate locked safes, no guns in an old shoeboxes here). My home country is subject to similar regulations and majority of people who own guns, either own them for hunting purposes or because they are a member of a shooting club. Even with this background I was somewhat surprised to learn of the draconian laws surrounding gun ownership in Japan. While citizens are allowed to own firearms for hunting or sport shooting purposes, the road to gun ownership is long and arduous. You not only have to pass a shooting range test with marks no lower than 95% and undergo a mental health evaluation at their local hospital. A thorough background check of the applicant and their family is naturally also conducted and if one happens to be lucky enough to pass all these requirements, it will only lead to a three-year licence, after which the whole process will start again. Civilians are not allowed to own handguns, let alone anything semi or fully automatic, leaving air rifles and shotguns pretty much the only guns available to purchase.

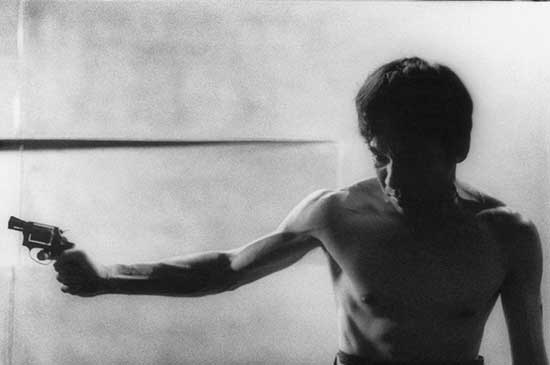

And what is my point here? Well, knowing this puts the core premise of Bullet Ballet in more understandable framework. The vehemently obsessive way that Goda goes about trying to track down where Kiriko could have possibly gotten a gun from may seem a bit bizarre at first, but knowing that the only people who might have access to a handgun will almost certainly have something to do with criminal activity, makes his behaviour much more coherent. Not only is Goda completely stunned by the sudden death of a loved one, but with the death comes questions of who this person really was? Did he not know the person he just spent ten years with at all? Was she involved with gangs or other criminal enterprises? Of all the ways of killing oneself, why would she choose to use a gun?

All these questions, together with crushing weight of his grief, leads Goda, literally and metaphorically, into some very dark avenues. He not only goes on a crazed mission of finding a gun of his own, but along the way gets more and more sucked into the criminal underbelly of the city and the brutality that comes with it. Over and over again he confronts the same gang members, getting himself repeatedly violently assaulted, making him increasingly desensitised toward violence and death. The same apathy is present in the young gang members he encounters. From mindless violence to Chisato’s risky games on subway platforms, to offhand comments about weapons that one should bring to a fight, they all are completely numbed toward the violent existence they live in. While the gun, the very article that took the life of his loved one, is the root of all the grief, it is also something that Goda obsesses over in almost fetishized manner. It is like a magic amulet that holds the key to moving on with his grief and without it, nothing can be solved. In a way this ends up being true, but not necessarily in a way one might expect. The violence and the nihilistic lifestyle that Goda finds himself sucked into, ultimately help him come to terms with death and in the end, perhaps even offer a form of redemption. The bleak tale of grief ends with almost a positive note and a feeling that Goda has found some kind of peace in his middle of all the despair.

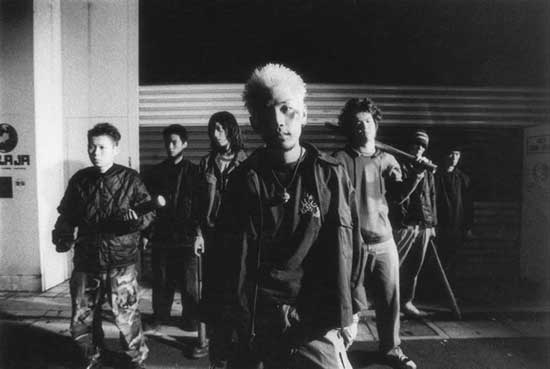

Stylistically Bullet Ballet is pure Tsukamoto. The story is told in his trademark dark monochromes with frenetic editing and Chu Ishikawa’s dynamic industrial score enhancing the atmosphere. It does not offer anything nearly as visually chaotic as Tsukamoto’s cyberpunk works, but the hints toward his past films and the genre are still there, the scenes of leather jacket wearing, teddy boy haircut sporting thugs bringing to mind the early works of Sogo Ishii, most prominently Burst City. These hints are subtle and perhaps not even intentional, but I for one could not help but to compare the similarities of Tsukamoto’s frenzied youths to the raw power or Ishii’s dystopian gang wars. Performances are great all around, with Tsukamoto himself really excelling in the role of Goda. As an actor, he brings and incredible intensity to almost any role he takes on, but something about this particular role seems to fit him perfectly. Mano’s role as the aloof Chisato is equally enjoyable to watch, painting a picture of a young woman completely numb to the carnage around her.

If I had to moan about something it is the slight lack of focus the film suffers from midway through, momentarily losing the manic energy of the beginning and getting lost in the gang warfare and its mindless vigilantism, but in the grand scheme of this, this is a very minor gripe.

Bullet Ballet is definitely a film that warrants a second look. Even for a fan of Tsukamoto’s work like myself, it does not seem to fully reveal itself after just one viewing. It will not please all of his fans, I myself am in two mind about it, but I guarantee it will stick in your mind, leaving you ponder the style, the meaning and everything else in between for a good while after.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews