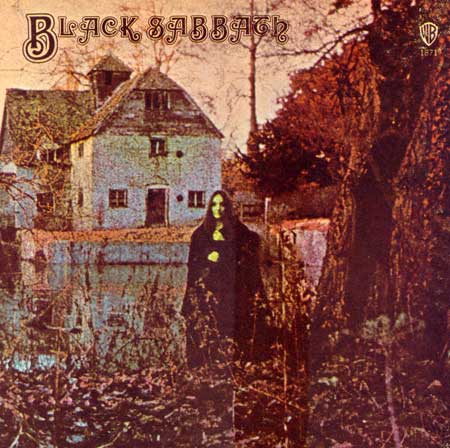

Released in the UK on Friday the 13th of February, in the first year of the dawning decade, Black Sabbath’s self-titled debut (named, like the band itself, after Mario Bava’s 1963 horror film) was the distorted “shot heard ‘round the world” of occult/doom rock. Not only did these working class boys from Birmingham, England deliver a haunting, gloomy album cover (a grainy shot of a cloaked, witch-like figure in front of a fifteenth century Oxfordshire watermill), and lyrics detailing bleak, even frightening, subject matter; for the first time, the music itself was the sonic embodiment of heavy, gothic menace, and yet it remained rooted enough in bluesy rock forms and even soul/funk rhythms to retain widespread appeal for the era’s teenage rock fans. The tunes, all built on colossal-yet-catchy riffs, were just too well put together, and too much fun, for the new breed of young stoners to be scared out of their headphones by the hellish horror imagery of the lyrics.

band itself, after Mario Bava’s 1963 horror film) was the distorted “shot heard ‘round the world” of occult/doom rock. Not only did these working class boys from Birmingham, England deliver a haunting, gloomy album cover (a grainy shot of a cloaked, witch-like figure in front of a fifteenth century Oxfordshire watermill), and lyrics detailing bleak, even frightening, subject matter; for the first time, the music itself was the sonic embodiment of heavy, gothic menace, and yet it remained rooted enough in bluesy rock forms and even soul/funk rhythms to retain widespread appeal for the era’s teenage rock fans. The tunes, all built on colossal-yet-catchy riffs, were just too well put together, and too much fun, for the new breed of young stoners to be scared out of their headphones by the hellish horror imagery of the lyrics.

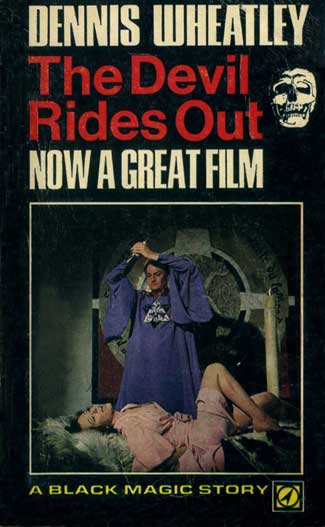

The band’s bassist and main lyricist, Terence “Geezer” Butler, had gone through a phase of dabbling in the Dark Arts himself, and had absorbed the satanic thrillers of British author Dennis Wheatley (whose classic 1934 novel The Devil Rides Out had been adapted by Hammer Films into one of the earliest successful occult fright flicks in 1968). The album’s opening track, and its creative centerpiece, “Black Sabbath” – eerily opening with the sound of distant church bells in a raging thunderstorm – was a statement of intent for the band’s career, and for a new form of heavy rock music. Butler’s malevolent tale of demonic visitation – based, he claimed, on an actual, terrifying personal experience – was delivered by vocalist John “Ozzy” Osbourne in the desperate wail of a man staring straight into the smoldering embers of Hell itself. The song’s over-driven, feedback-soaked slabs of riffing (making use of the tritone musical interval, famously banned by the medieval church for its “evil” sonic qualities and termed the diabolus in musica – “the Devil in music”) and frantic soloing by guitarist Tony Iommi and the pounding, grooving drums of Bill Ward made the whole affair sound as musically irresistible as it felt morally illicit.

The band’s bassist and main lyricist, Terence “Geezer” Butler, had gone through a phase of dabbling in the Dark Arts himself, and had absorbed the satanic thrillers of British author Dennis Wheatley (whose classic 1934 novel The Devil Rides Out had been adapted by Hammer Films into one of the earliest successful occult fright flicks in 1968). The album’s opening track, and its creative centerpiece, “Black Sabbath” – eerily opening with the sound of distant church bells in a raging thunderstorm – was a statement of intent for the band’s career, and for a new form of heavy rock music. Butler’s malevolent tale of demonic visitation – based, he claimed, on an actual, terrifying personal experience – was delivered by vocalist John “Ozzy” Osbourne in the desperate wail of a man staring straight into the smoldering embers of Hell itself. The song’s over-driven, feedback-soaked slabs of riffing (making use of the tritone musical interval, famously banned by the medieval church for its “evil” sonic qualities and termed the diabolus in musica – “the Devil in music”) and frantic soloing by guitarist Tony Iommi and the pounding, grooving drums of Bill Ward made the whole affair sound as musically irresistible as it felt morally illicit.

While not every song Sabbath recorded was as literally satanic as track one of their debut, the foursome made that wicked vibe their calling card. While forging a wildly successful career over most of the ‘70s, and even letting their musical style evolve somewhat over the decade, they managed to creatively exploit and expand their characteristic doomy trappings. Album cover art, song titles, lyrics which continued to occasionally mention devils and demons, and their signature heavy sound made them famous, beloved, reasonably wealthy (poor contract signings from their early days shadowed them for years), and spawned generations of imitators.

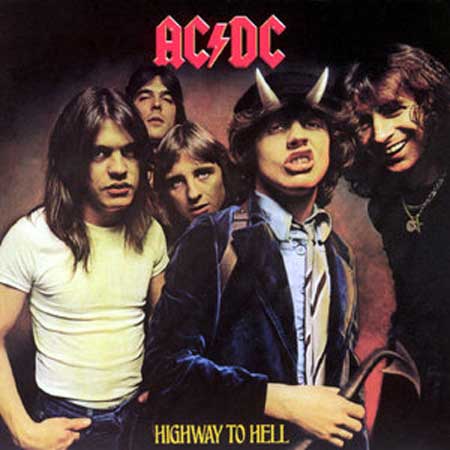

Near the end of Sabbath’s nearly decade-long reign with its original line-up, a group of five scruffy upstarts from Australia began making inroads into worldwide mainstream popularity with their high-energy, super-charged take on classic 1950s rock ‘n’ roll. Going by the unlikely name of AC/DC, the band’s first few albums are entirely devoid of any references to the occult, the lyrics far more concerned with roguish frontman Bon Scott’s leering double entendres and prurient puns. By the late ‘70s, however, perhaps simply because it was in vogue for hard rock music at the time (thanks to their forerunners in Black Sabbath), the band began to sprinkle a few diabolical references into their song titles and lyrics (1977’s “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be,” 1978’s “Rock ‘n’ Roll Damnation”) even if their context remained largely metaphorical.

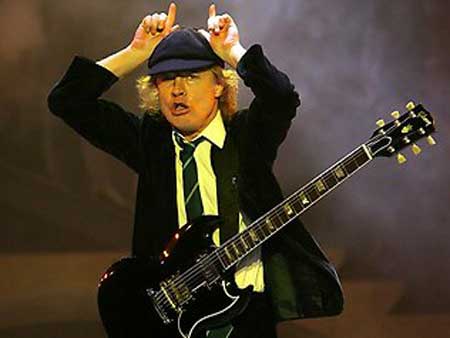

With their breakthrough album, however, 1979’s Highway to Hell, these references began to stack up. The LP’s title track impishly pushed the Hell and Satan imagery to its metaphorical limit, while the lyrics of the bluesy “Night Prowler” (a thematic descendant of the Rolling Stones’ own “Midnight Rambler”) painted an uncharacteristically dark tale of late-night murder – a chilling narrative choice that would soon return to haunt them. The album’s cover image, with the band’s eyes cloaked in heavy shadow, a bare-chested Bon Scott sporting a pentagram pendant, and sneering guitarist Angus Young enhanced with airbrushed-in devil’s horns and a barbed tail, caught the attention of parents – and moral crusaders – as much as the music.

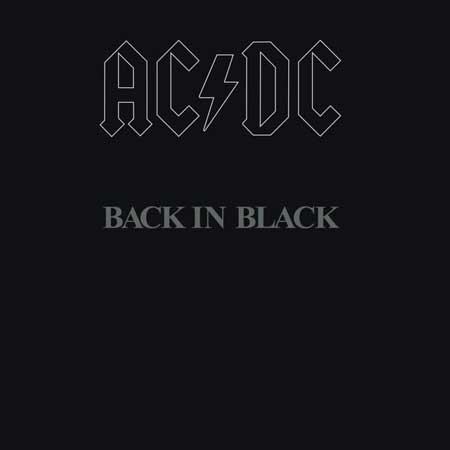

For the first time, as unlikely as it seemed for what was basically a blues-and-boogie rock ‘n’ roll band, AC/DC began to be lumped in with occult rock and metal acts like Black Sabbath and others which had emerged in the 1970s. After the tragic, alcohol-related death in early 1980 of singer Bon Scott, AC/DC’s next LP, Back in Black (which opened with the ominous tolling of bells, recalling Black Sabbath’s debut) featured new vocalist Brian Johnson, and continued the band’s recent penchant for casual satanic references and occasionally dark subject matter. After exploring sinister lyrical themes one more time, on 1981’s For Those About to Rock We Salute You, this songwriting trend tapered off drastically for the rest of the band’s career, but in many circles, the damage had been done.

Once the Reagan-era 1980s had dawned in America, a new fervor for modern-day witch-hunting quickly seemed to take hold in churches, schools and parents’ groups across the country, and with the aid of the new sensationalism-hungry journalism of popular “news magazine” TV programs, the “Satanic Panic” of the ‘80s was born. Combining a trendy media obsession with the idea of ritual child abuse, theories of subliminal, even “backward masked” messages in music, fanciful fears of the rise of Devil-worshipping cults all over the country, and the newfound power of Evangelical Christian groups as a sociopolitical force, all cloaked in “protect-the-children” earnestness, this movement needed a highly visible, easily identified enemy to blame, and nothing fit the bill more perfectly than cartoonishly “evil” rock groups

By the mid-1980’s there were rock and metal bands that were far more transgressive and intentionally offensive in their imagery and lyrics than Black Sabbath, its former vocalist Ozzy Osbourne (by the ‘80s a successful solo act) and AC/DC; more musically extreme metal bands that had formed in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, such as the UK’s Angel Witch, Venom and Witchfynde, Denmark’s Mercyful Fate, and the US kings of demonic thrash, Slayer, marketed themselves as explicitly, excessively Satanic. In the early-mid ‘80s, however, these over-the-top metal acts were far too underground, a virtually unknown niche genre to the mainstream, to be of any interest to the churches, schools and parents who were eager to publicly condemn a few easy, high-profile villains in order to protect America’s youth. More than anything else, Black Sabbath, Ozzy Osbourne and AC/DC were victims of their own remarkable success and popularity in mainstream America.

Despite the fact that Sabbath and Ozzy’s occasional satanic lyrical content was usually warning the listener away from involvement with diabolical forces, and that AC/DC had, mostly metaphorically, referenced the occult in only a small handful of tracks in their vast catalog of songs, these bands were targeted for a smear campaign, first via church pamphlets and fire-and-brimstone sermons, and eventually through more conventional magazine articles and TV news segments with eye-catching, alarmist titles. The Parents Music Resource Center, a Washington, D.C. watchdog committee co-founded by Tipper Gore (wife of future US presidential nominee Al Gore), and dedicated to requiring warning stickers on objectionable music releases, placed both Black Sabbath and AC/DC on their infamous list of the “Filthy Fifteen” bands of which parents should be especially wary. The situation became so ludicrous that in many quarters it was stated, in all seriousness, that AC/DC’s moniker (inspired by the “alternating current/direct current” electrical label on a sewing machine and intended to denote the power of the band’s music) was actually an initialism that stood for “Anti-Christ/Devil’s Children.”

Despite the fact that Sabbath and Ozzy’s occasional satanic lyrical content was usually warning the listener away from involvement with diabolical forces, and that AC/DC had, mostly metaphorically, referenced the occult in only a small handful of tracks in their vast catalog of songs, these bands were targeted for a smear campaign, first via church pamphlets and fire-and-brimstone sermons, and eventually through more conventional magazine articles and TV news segments with eye-catching, alarmist titles. The Parents Music Resource Center, a Washington, D.C. watchdog committee co-founded by Tipper Gore (wife of future US presidential nominee Al Gore), and dedicated to requiring warning stickers on objectionable music releases, placed both Black Sabbath and AC/DC on their infamous list of the “Filthy Fifteen” bands of which parents should be especially wary. The situation became so ludicrous that in many quarters it was stated, in all seriousness, that AC/DC’s moniker (inspired by the “alternating current/direct current” electrical label on a sewing machine and intended to denote the power of the band’s music) was actually an initialism that stood for “Anti-Christ/Devil’s Children.”

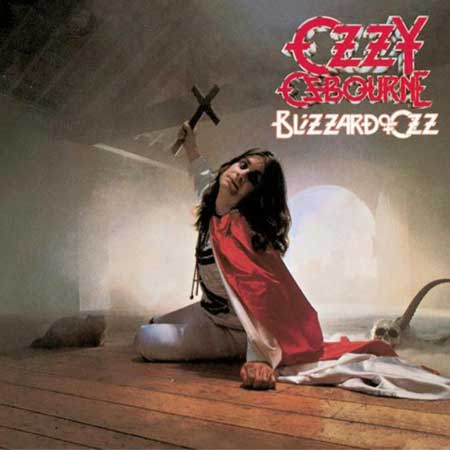

Things took a more serious turn in 1986 when Osbourne was sued by the parents of John Daniel McCollum, 19, a suicide victim who had shot himself while listening to Ozzy’s 1980 solo debut Blizzard of Ozz, which contains the track “Suicide Solution”; the case was eventually dismissed. Worse still, AC/DC was, to the band’s utter dismay, closely linked to the grisly 1984-’85 crime wave of savage California serial killer (and avowed Satanist) Richard Ramirez, known as the “Night Stalker,” when his “AC/DC” logo hat was found at the scene of one of the killings, and a childhood friend claimed in an interview that Ramirez was a dedicated fan of the band, and in particular of the album Highway to Hell. Horrifically, Ramirez’s technique of quietly invading the homes of his sleeping victims happened to closely mirror the scenario of AC/DC’s song “Night Prowler” from that very LP; the link was quickly made by the media and fed to the public: AC/DC “inspired” the barbaric Night Stalker slayings. For a time, the name AC/DC could not be mentioned on TV news without accompanying courtroom footage of Ramirez holding up his pentagram-carved palm and exclaiming “Hail Satan!”

The mostly teenaged fans of the bands were either amused or thrilled by the taboo status of their favorite rockers. Occult graffiti was a common sight in the ‘80s, and one rarely came across spray-painted pentagrams, inverted crosses, or the number “666” without the addition of “Ozzy,” “Black Sabbath” or “AC/DC” scrawled somewhere in the mix. The more hysterical the parents got, the more the kids seemed to love the bands.

By the early 1990s, as things like the Persian Gulf War gave the American public more immediate, tangible concerns, the Satanic Panic of the ‘80s slowly faded into memory, for all but the most extreme, fringe Evangelical organizations. Toward the end of the decade, as Ozzy began years of sporadic reunions with his Black Sabbath band mates, and AC/DC continued to tour and release albums, both bands transitioned into “Elder Statesmen of Rock” status (what the industry refers to as “Legacy Acts”). Both bands’ popularity has actually grown in recent years, after some late ‘80s-early ‘90s career doldrums.

There seems to be a very real sense that the era of huge arena rock groups undertaking major tours is coming to a close. There is a thriving underground movement of heavy rock bands that steadfastly deny any musical progress past 1973 or so (“Stoner Rock,” “Doom Rock”; the list of sub-genres is endless), and there’s currently a particular uprising of US and UK acts which cling to the almost innocent vibe and visuals of late ‘60s-early ‘70s occultism and witchcraft, most of whom sound musically like early Sabbath, and several of which (the UK’s Purson and Canada’s Blood Ceremony, to name just a couple) include a strong nod to Coven by featuring a witchy chanteuse as frontwoman. Sweden also contributes heavily to modern day underground occult rock, with one breakthrough (and quite theatrically Satanic) act, Ghost, bordering on wide mainstream popularity. With all of these bands, the occult elements, whether subtle or excessive, as perceived today, have become something of a “retro” flavoring and nothing more, along with vintage instruments and styles of dress; no one seems to be seriously threatened by the presence of that old “Devil in music” anymore.

Both Black Sabbath and AC/DC survived the frenzied condemnations of the 1980s and came out the other side to continue, against all odds, to bring joy to thousands, perhaps millions of fans of all ages. Their popularity with the general public, and their continued success, hard-won and built the old-fashioned way – through superior songcraft and relentless touring – and, absurdly, the reason they were targeted by self-styled moral authorities a generation ago, remain the qualities that have carried them through all these years later.

Each band’s current tour still offers a playful nod to their once-fearsome reputations, visual stylings which don’t seem to scare anyone: Sabbath (who never have let go of their comic-book devilry) begins each show with an intro video featuring a giant demonic creature destroying a modern city; AC/DC’s stage design incorporates an enormous pair of glowing devil’s horns atop the lighting rig (and a popular item at the merchandise booth is a wearable set of similarly horned headgear), recalling Angus Young’s look on that long-ago album cover. These two groups were once feared as insidious, malevolent forces, agents of Lucifer infiltrating suburban America, intent on corrupting the very souls of the nation’s youth; in 2016, today’s children are happily singing along to concerts by these veteran bands, arm-in-arm with their proud parents, brought together by the music. In the end, it’s the music of Black Sabbath and AC/DC that’s important, and it’s the music that will go on. Try as he might, even Satan himself couldn’t take that away; the music was always just too good – too damned good.

Check out Music and the Occult Influence – Part1

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews