SYNOPSIS:

“Jesus is but a humble carpenter when a prince, Judah Ben-Hur, is wrongfully forced into slavery. After years of hard labour, he sets out to take revenge on the treacherous Roman friend who betrayed him, culminating in an epic chariot race.”

REVIEW:

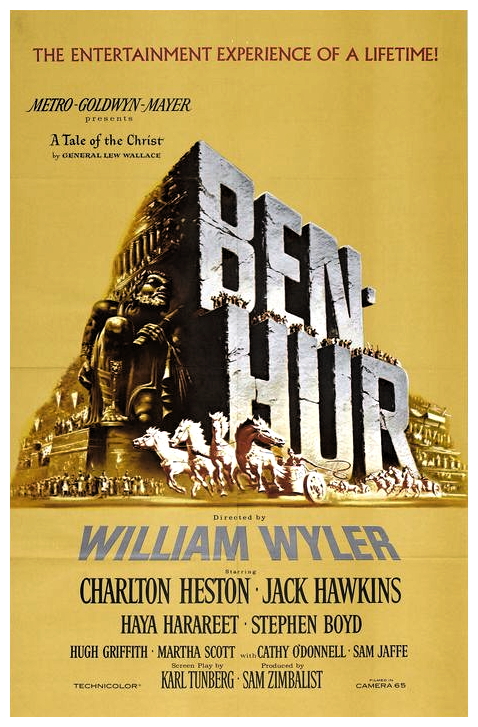

Television producer Mark Burnett – responsible (although some might use the word ‘guilty’) for some of the most inexplicably popular reality shows ever, like The Voice, Survivor, The Apprentice and Shark Tank – has recently made the somewhat unusual leap to big-screen religious epics by hiring Russian director Timur Bekmambetov to re-introduce Ben-Hur (2016) to new audiences. Just this week it was declared a flop at the box-office with an overall loss of US$120m. British actor Jack Huston, grandson of fabled director John Huston and nephew of Angelica Huston, balked at re-enacting Hollywood’s holy cow: “I sort of gaped a little and was like, ‘Really?’ But I read it and was so surprised with the re-imagining of this beautiful story, a story I now believe can be told and told again for different audiences. Whenever someone asks me, ‘Why would you remake something like Ben-Hur?’ I point out that this is actually the fourth time it’s been remade. There’s always room for a modern audience where a lot of people haven’t seen its predecessor, and we have a lot more at our fingertips technology-wise. I loved the Wyler version, and I would be the first person to say, ‘Oh, don’t do that,’ if I felt in any way it wasn’t going to hold up. But now I feel we’ve created something incredibly special.”

After the second version of Ben-Hur (1925) was released, an MGM executive was quoted, “Nothing like it has ever been, nothing like it will ever be, and nothing like it ever should have been!” How wrong he would prove to be. General Lew Wallace‘s novel Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ (1880) was one of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century. Set in the seventh year of Augusta Caesar’s reign in the Roman province of Judea, it tells the story of a Roman commander named Messala – Judea born-and-bred – who returns to take command of the garrison in Jerusalem. There he is reunited with his boyhood friend, an upper-caste Jew named Judah Ben-Hur. But what was once a close relationship quickly flounders in the reality of Roman occupation. Judah refuses to name Jewish patriots and Messala sentences him to the slave galleys and his family to prison. It is through the trials of Ben-Hur – Christ’s exact contemporary – that we see the suffering of the Jewish people under the domination of Rome.

A publishing sensation, the novel soon spawned America’s most successful theatrical production, an enormously popular stage spectacle that featured as its climax a live chariot race, run with up to eight horses at full gallop on a giant treadmill, and sold an estimated twenty million tickets. The emerging film industry quickly took note and the novel was filmed, “In sixteen magnificent scenes with illustrated titles!” condensed into just one reel, about ten minutes long. Outraged by the cavalier treatment of the source material, the publishers promptly sued the movie’s producer and won, establishing for the first time the copyright of a published author in another medium. It wasn’t until the mid-twenties that the project was attempted again. After years of negotiation and preparation, Metro Studios sent a huge cast and crew to Italy to film Ben-Hur (1926). It would prove to be a disaster and everything that could go wrong did.

During the filming of the sea battle (staged with full-sized galleys built by Italian shipwrights) a raging fire sent hundreds of the extras overboard, including those who couldn’t swim (they had all signed documents declaring they could swim but many of them had lied just to get a paying job). Another rather suspicious fire in the property warehouse forced the cast and crew to desert Italy altogether and return to Hollywood, where most of the story had to be re-shot. Although the silent version of Ben-Hur was enormously popular, its huge production cost of US$4 million kept it from making a profit for about a decade. However, one of the many assistant directors on that project was the young William Wyler. It would eventually fall to him to direct the next Ben-Hur (1959), the most expensive and technically ambitious film ever produced.

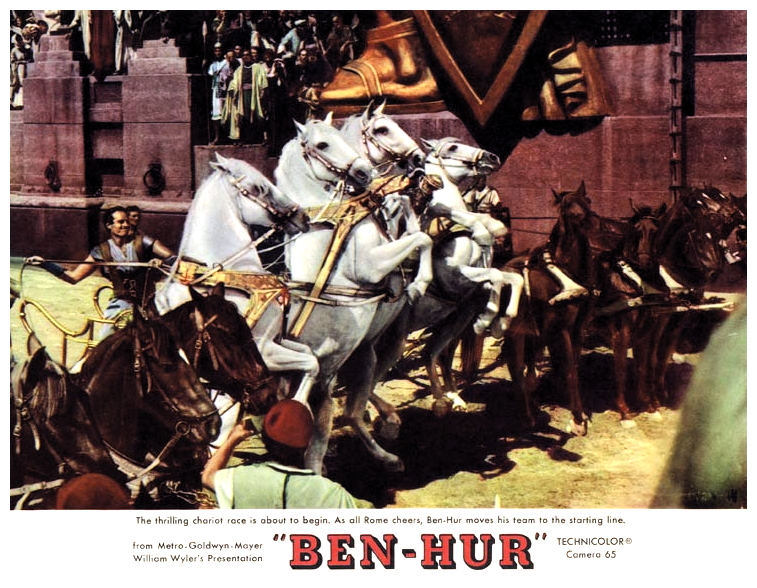

The fifties were a perilous time for the Hollywood studio system. Television was making enormous inroads into its audience and with only a few exceptions, movies were consistently failing to recoup their costs. Oddly, most of those exceptions were the lavish historical epics. Convinced that the biggest possible film would draw the biggest possible audience, MGM green-lighted a production that would imperil their very existence. The film was planned along the grandiose lines of a Cecil B. DeMille production – 50,000 people were required to make the movie, with 300 sets spread over 340 acres of land. One of those sets, the hippodrome, was the largest ever built, extending over 18 acres alone. The film utilised 65mm widescreen cameras to produce the very wide (2.76×1) print with a six-stripe magnetic soundtrack. Each camera cost about US$100,000 and required a crew of eight strong guys to lift it onto its pan head. One was later wrecked during the filming of the chariot race.

What’s more, many cinemas would be forced to upgrade their screening technology to cope with the sheer size of the projected image, and the script was also proving troublesome. Wyler dismissed the first version by Karl Tunberg as primitive and elementary. Then he had S.N. Behrman and Maxwell Anderson rewrite the dialogue, and still wasn’t happy. Luckily, English playwright Christopher Fry was around to adjust the dialogue, and novelist Gore Vidal was on hand for the first month and a half of location shooting and was asked to contribute to the motivational spine of the conflict between Messala (Stephen Boyd) and Judah (Charlton Heston). They are like brothers reunited, and embrace each other warmly in the long stone-columned hallway. They challenge each other to a friendly competition, hurling javelin spears exclaiming, “Down Eros! Up Mars!” Their friendship is still close in every way so, to make the scene playable, Vidal pulled Boyd aside and had him play the part as though he were meeting his old lover, but not to let Heston know he was doing so.

Casting also proved to be a headache. Paul Newman, who had starred in Victor Saville‘s stone-faced biblical epic The Silver Chalice (1955) turned down the role of Judah vowing he would never wear a cocktail dress ever again. Burt Lancaster and Rock Hudson were also offered the role before Heston agreed to come on board for the duration. Another blow came five months into the production’s seven-month shoot, when producer Sam Zimbalist passed away. Wyler said, “It was if the roof had fallen in on me. I felt alone. I’d never felt alone with Sam around.” Tempting lightning to strike twice, the MGM studio executives then asked Wyler to take over as producer as well as director. When it came time to film inside the galley, it was discovered that the huge 65mm cameras wouldn’t fit. The ship had to be taken out of the pond, sawn in half lengthwise and placed in an Italian soundstage. The oars wouldn’t fit in the soundstage, so they had to cut them off just beyond the hull. This resulted in extremely lightweight oars which, when rowed by the actors, didn’t look believable, so the oars were put on spring-and-hydraulic piston mechanisms that are normally found on self-closing doors.

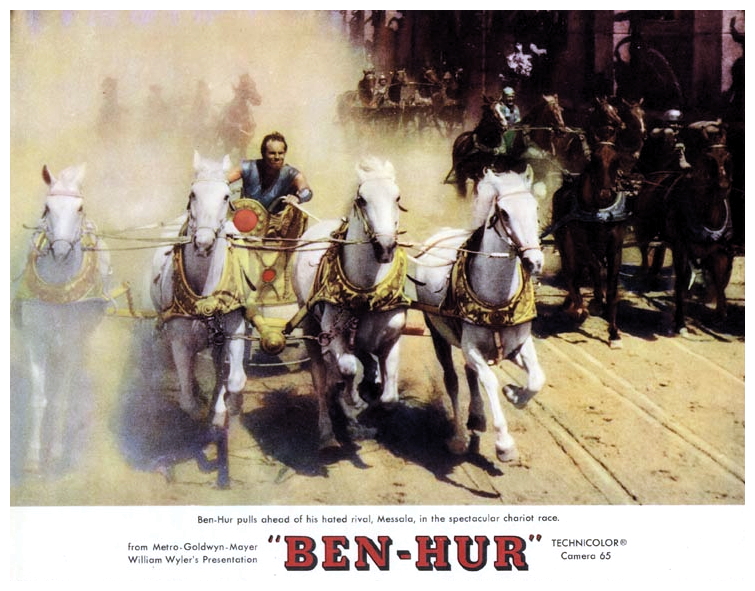

The naval battle scenes were shot using scale models on a specially constructed pond. An unforeseen problem concerned the colour of the water, it was too brown, so they hired a chemist to develop a dye to colour the water azure Mediterranean blue. He dumped a huge sack of the dye onto the pond which, instead of turning the water blue, formed a hard crust on the surface. An extra who fell into the water actually turned blue, and was kept on the MGM payroll until it wore off. Heston was by this time an experienced charioteer after hours of training with stuntman Yakima Canutt, but that wasn’t enough to save him from a minor spill. At the beginning of the race, he shook the reins and nothing happened. Finally someone way up on top of the set yelled ‘Giddy-up!’ and the horses roared into action, flinging Heston backward off the chariot. Although there were probably white horses in Italy, the four used in Ben-Hur were flown in from Czechoslovakia.

The famed chariot race sequence remains a text-book example of how to shoot a race and it has been copied ever since. The sequence was directed by Canutt, and one of Canutt’s sons doubled for Heston. During one of the crashes in which Judah’s horses jump over a crashed chariot, the younger Canutt was almost thrown from his chariot. He managed to climb back in and bring it back under control, and the sequence looked so good that it was kept in the final release. Messala’s chariot disintegrates and he is pitched out, dragged behind and trampled by horses. Unfortunately, you can clearly see that the figure pitched out, dragged and trampled is a dummy. A closeup of Boyd being dragged is cut into the sequence, but the distance shots are all done with a stiff figure. Thanks to sequences like this, the chariot race has a 263-to-1 cutting ratio – 263 feet of exposed film for every one foot used, the highest for any widescreen sequence ever filmed.

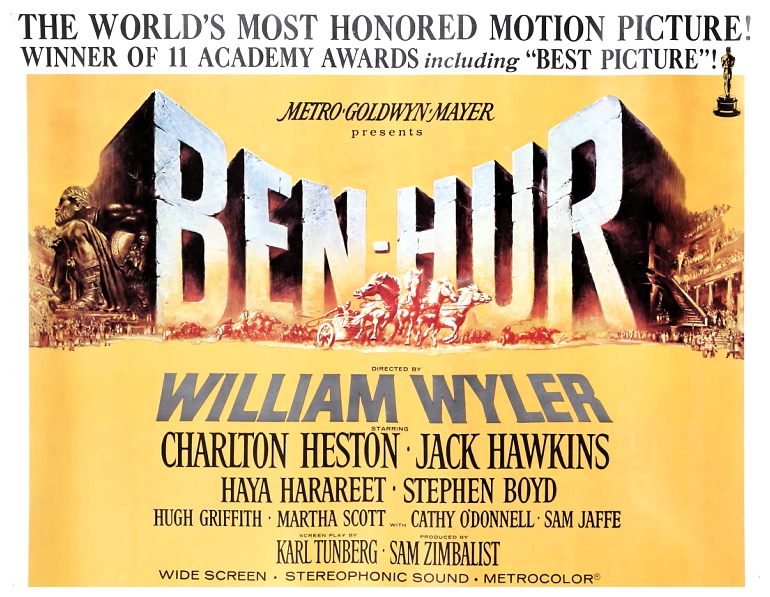

In the end though, all that effort proved to be worth it. Ben-Hur was nominated for twelve Oscars and won eleven of them, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Heston) and Best Supporting Actor (Hugh Griffith). It would be a feat unequaled for forty years, until the launching of James Cameron‘s Titanic (1997). It also sparked an unlikely merchandising bonanza – new editions of the novel, Ben-Hur perfumes and neckties, T-shirts, candy bars, toys, chariot scooters, even Ben His-and-Hurs bath towels. Having demonstrated to you the perils of probing the dark depths of Hollywood, I’ll vanish into the night, after first inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Ben-Hur (1959)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews