SYNOPSIS:

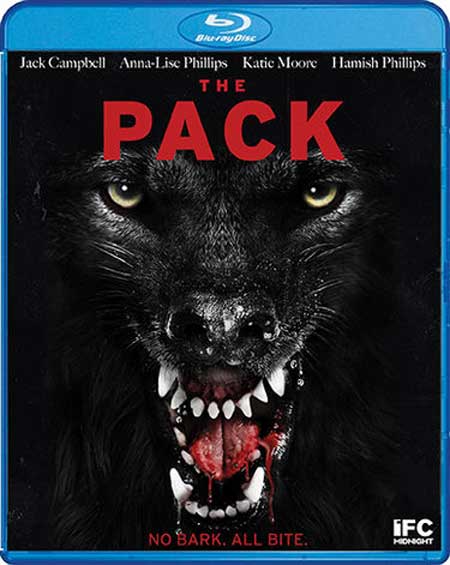

In Australia’s outback, a family struggles to keep the wolves from the door when a bank tries to foreclose on their land; but it soon becomes clear the family has even bigger problems when a pack of vicious dogs literally arrives at their door – and they’re looking for something to eat.

REVIEW:

The film begins with beautifully crafted establishing shots of the brightly lit Australian outback which give way to a dusky montage of the forest near the local farming community, quickly establishing the funereal tone of the film. Music flows up from silence into a soft hum, low notes bending into one another, and then fading out, sometimes sounding like a morose, ghostly howl passing just beyond the ridge. The basic theme of humans-as-prey is set up with a simple, but well executed, segment showing the dog’s first kill before moving onto the main focus, which is the Wilson family and their fight for survival.

The credits roll over more establishing shots, this time of the idyllic Wilson farm; each member of the family is given a brief, prosaic scene in order to familiarize themselves as characters: Henry Wilson (Hamish Phillips) as the occasionally somber and withdrawn young son, Adam Wilson (Jack Campbell) as the embattled father and farmer, Carla Wilson (Anna Lise Phillips) as the weary but stoic mother, and Sophie Wilson (Katie Moore) as the rebellious and cranky teenage daughter yearning for freedom.

Tempers flare when the slithery banker (Charles Mayer) shows up and suggests the Wilsons sell the farm due to falling income and commonly overdue mortgage payments; when Adam doggedly refuses, the banker states foreclosure will be eminent, at which point he’s booted from the house and told never to come back. Not long after leaving, the banker conveniently stops his car on the edge of the forest for a little bathroom break and is expeditiously dispatched with canine acuity, fulfilling the audience’s need for soulless-banker cathartic release.

Light fades and things calm as the scene shifts back to the Wilsons and their ever so slight bonding; this stilted domestic bliss is soon interrupted by Carla’s need to check the fuse box and the unfortunate timing of wild, man-hungry beast-dogs skulking around the perimeter of the house as Adam looks for the family dog in the woods; it’s when he’s met with several pairs of glowing eyes, low growls, menacing howls, and shadowy canine figures chasing him back home, that he realizes something dangerous might be going on.

First-time feature director from Australia, Nick Robertson, directs this literalized metaphor with mature skill and a steady eye; he brings technical nuance, storytelling precision, and rich visual style to the film, all talents he picked-up in the Australian advertising market while directing award-winning commercials. He keeps the inflection at an even, tenebrous balance throughout while at the same time expertly maintaining a high level of profluence.

The music, by Tom Schutzinger, is consistently haunting; it crawls under the skin and seductively draws the viewer into the compressed darkness of the surrounding woodlands without making itself obvious or intrusive and nudges the viewer into a deeper receptive state conducive to manufactured anxiety. Benjamin Shirley’s luscious cinematography has a complex, honeyed depth dripping with color; even in the darkest of scenes, he brings out the rich possibilities and the menacing nature of all that’s happening; obviously benefiting from a close working relationship with Robertson, he keeps the story visually tight and the camera usage fluid and engaging, which adds an energy that could easily be lost by those lesser skilled in the profession.

The acting of everyone involved is of the highest of standards, riding on a proficiency that’s all too often deemed unnecessary in the frequently slap-dash world of horror films; the choices the actors make, even in the most unoriginal of scenes, are consistent, believable, and well-considered.

On the down side, we have the script by Evan Randall Green. Unfortunately, it’s tedious, hackneyed, and derivative; it’s less an actual script than a stitched together Frankenstein monster consisting of many timeworn clichés from the horror genre: a shower scene with the lights out and the soft image of a figure on the other side of the shower curtain

– check; the shower curtain is suddenly thrown open to reveal nothing – check; a close-up of water circling down the shower drain – check; scenes where florescent lights aren’t working properly and flicker on and off for no apparent reason – check; scenes where, for no apparent reason, flashlights and radios stop working at the most inopportune time – check; scenes where, for no apparent reason, flashlights and radios start working at the most inopportune time – check; trite, moth-eaten family dynamics where the father is obstinate, the mother is weary, the teenage daughter is lippy, and the son is slightly knowing and withdrawn – check.

Even though this is only his third outing as a scriptwriter, Evan Green can do better. Or at least I hope he can; the premise for this film is good, it’s solid, and it could have been a good story if Evan had tried to sidestep at least some of the overworked themes and ideas. Hopefully, he’ll do so next time, because, if there’s any justice in the filmmaking world, the first-class talent involved with The Pack should never be wasted on another unimaginative script like this again. Check, please!

Bonus Features

- The Making Of The Pack Featurette

- Theatrical Trailer

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews