SYNOPSIS:

“In a generic European country of the late sixties, Diabolik is an anti-hero whose life consists on preparing schemes to steal government money and make a fool of the entire police department. Helped by his gorgeous girlfriend Eva, Diabolik begins by stealing a few dollars, but his duel of wit and audacity with police inspector Ginko will take them both to some extreme consequences.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Dino De Laurentiis was something of an enigmatic figure in filmmaking. Generally dismissed as a philistine, rudely nicknamed Dino De Dum-Dum by one British movie magazine, he has nevertheless been described by director David Cronenberg (who is nobody’s yes-man) as, “A very interesting man, one of the last of the old-style moguls. It’s pretty exhilarating working with him, because he obviously loves to solve problems. There’s a great deal of energy and dynamics going on around him.” On the other hand John Milius, who directed Conan The Barbarian (1982) said, “His methods are unsound. Dino is just like bad weather. He’ll pass, but meanwhile you have to contend with it.” Contrary to popular myth, the films he produced are by no means always aesthetic disasters. Indeed, at the beginning of his career De Laurentiis was a name to conjure with among intellectuals, for he produced Federico Fellini‘s early masterpieces La Strada (1954) and Nights Of Cabiria (1956), and would continue to finance ambitiously artistic films, such as Ingmar Bergman‘s The Serpent’s Egg (1977).

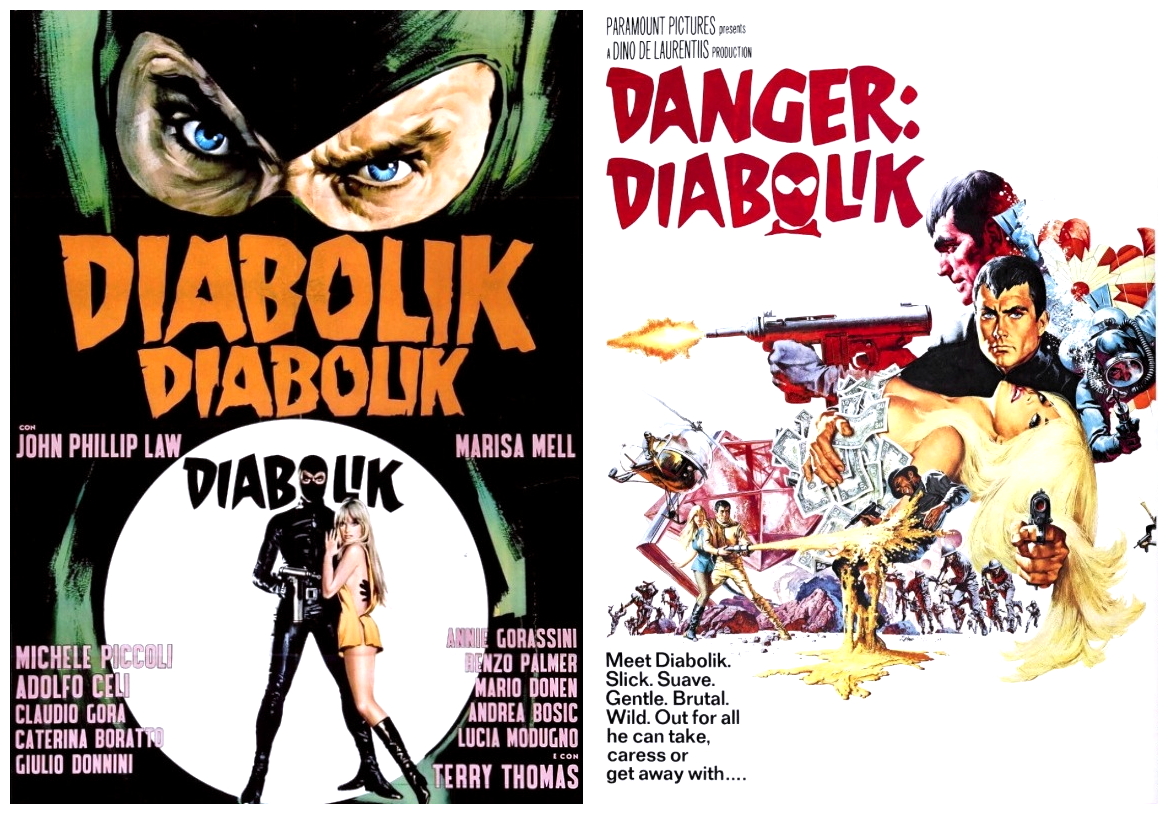

The damning of De Laurentiis by fans of fantastic cinema began with King Kong (1976), but he was making fantasy films a long time before that. An early example is Danger: Diabolik (1968) directed by the unevenly brilliant Italian Mario Bava. This, like his Barbarella (1968) produced six months later, was based on a European comic strip. Inspired by a number of previous anti-heroes in Italian and French fiction, Diabolik was a master thief created by sisters Angela Giussani and Luciana Giussani in 1962 to appear in monthly black-and-white comic books. Film producer Tonino Cervi was the first to recognise Diabolik’s cinematic potential. He actually wanted to make a new version of Flash Gordon but dismissed as being too expensive: “Flash Gordon would be a sensational success but it would cost as much as Cleopatra (1963). I have to settle for something more modest, so I’m doing Diabolik.”

Cervi purchased the film rights and negotiated a distribution deal with De Laurentiis, who advanced 70 million lira of his own money and struck a co-production deal between Italy, France and Spain, with a total budget of about 400 million lira. First draft script was by comic writers Corrada Farina and Pier Carpi. Second draft was written by screenwriters Fabrizio Onofri and Giampiero Bona, who were ordered to tone down the violence and turn up the humour. Filming started in 1965, directed by Seth Holt starring Jean Sorel as Diabolik, Elsa Martinelli as his loyal partner Eva Kant and George Raft as the bad guy, but shooting halted when Raft became unwell and was replaced with Gilbert Roland. The footage shot so far was so bad that De Laurentiis stopped everything – he needed a new director and a better script. Because of the stoppage, France dropped out and Spain confiscated the cameras, costumes and props that had been rented by the Italian company which nearly bankrupted it.

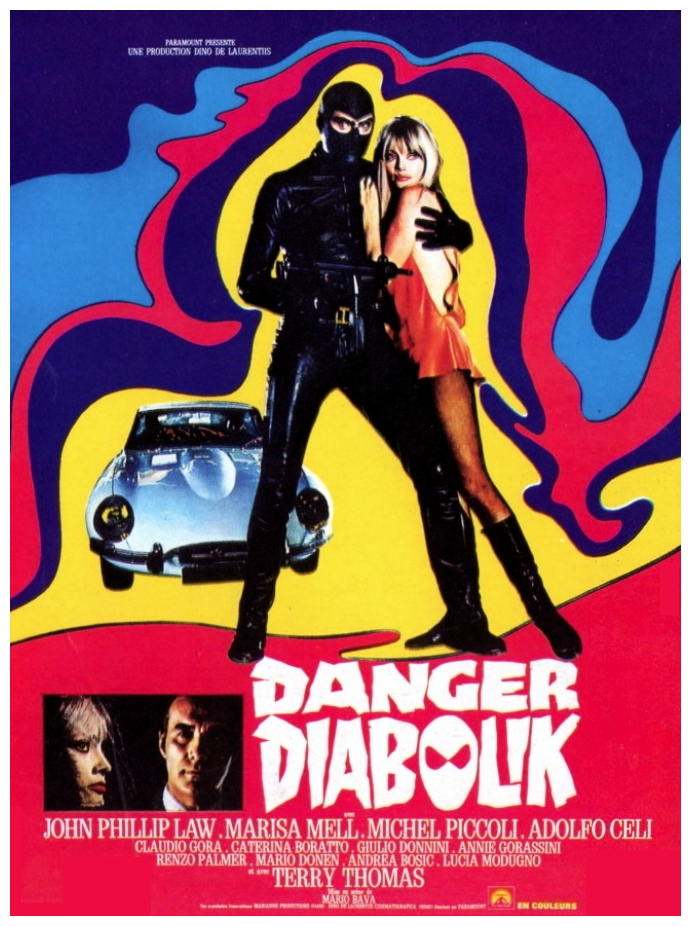

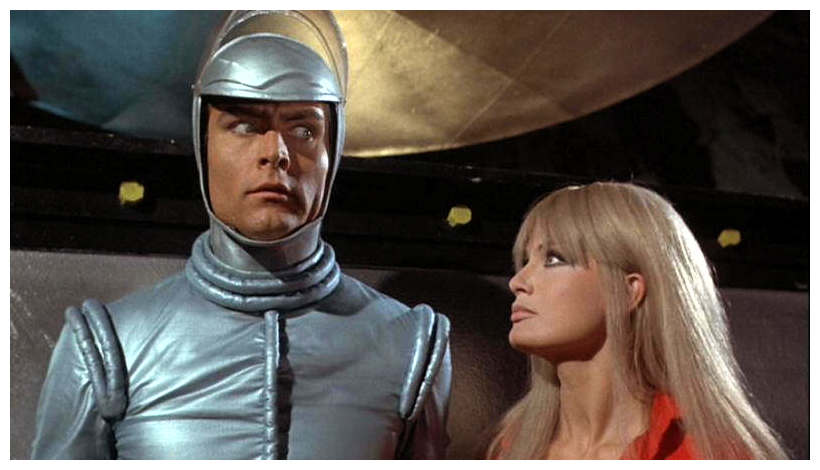

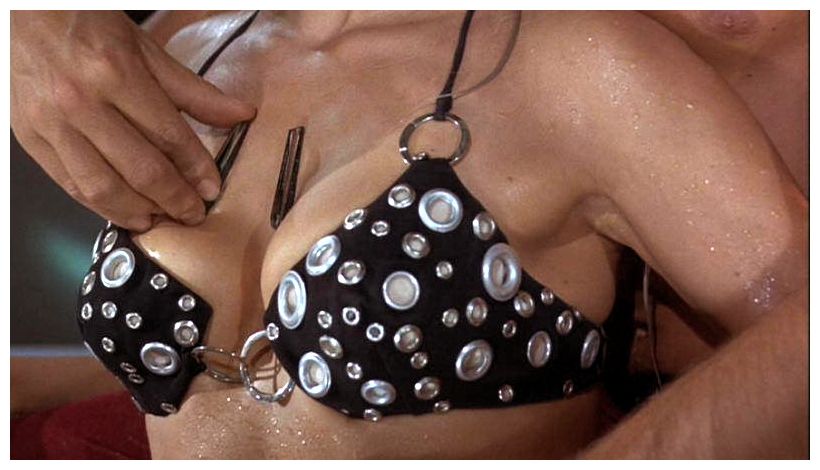

De Laurentiis cut the budget in half, acquired alternate backing from Paramount Studios, and hired Mario Bava as director. He cast Adolfo Celi as the villain Valmont, Michel Piccoli as Inspector Ginko, Marisa Mell as Eva, and John Philip Law, fresh from the set of Barbarella, as Diabolik. With Bava came cinematographer Antonio Rinaldi and editor Romana Fortini. Special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi was hired to design the sets, music composed by maestro Ennio Morricone, and the new script had four writers (Mario Bava, Brian Degas, Tudor Gates, Dino Maiuri) adapting three original comic stories. A year and a half later the project was back on track. Stylistically, Danger: Diabolik (1968) falls somewhere between Joseph Losey‘s Modesty Blaise (1966) and Roger Vadim‘s Barbarella (1968) but, unlike those films, Diabolik is a Spider-Man-like character from the wrong side of the tracks. Diabolik (John Philip Law) is an international master thief who has hit the height of his profession after a series of robberies including hijacking a ten-million-dollar gold shipment.

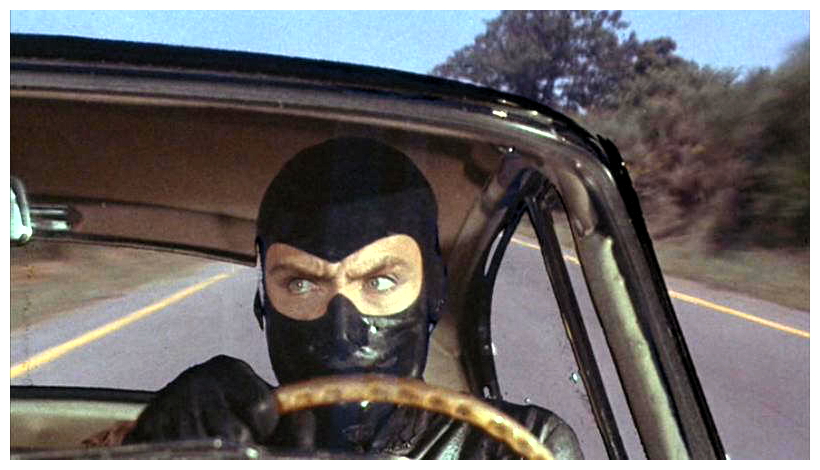

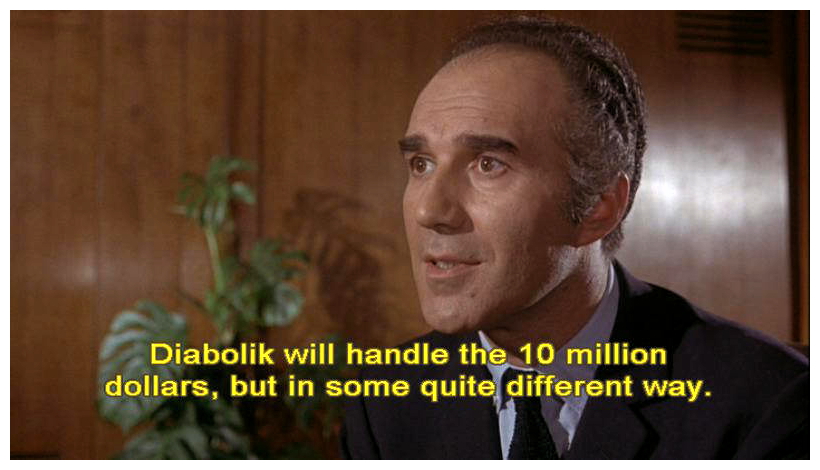

Under pressure from the Minister of the Interior (Terry-Thomas), police inspector Ginko (Michel Piccoli) attempts to set a trap for him using a million-dollar emerald necklace as the bait. Nevertheless, Diabolik gets away with the loot. This comes over as one of the most enjoyable sequences in the movie, with Bava’s excellent use of distortion lens producing some remarkably dizzying effects. Diabolik’s human-fly-style heist and scaling the sheer wall of a villa results in a superb piece of high-tension filmmaking. Inspector Ginko, following the failed trap, collaborates with underworld chief Ralph Valmont (Adolfo Celi) to catch the master criminal. Valmont decides to kidnap Diabolik’s faithful girlfriend Eva Kant (Marisa Mell) but the elusive thief manages to not only rescue her and escape Ginko’s trap, but also blows up the nation’s tax records, to the delight of the general public. Finally, in a desperate all-out effort to capture Diabolik, all the remaining gold reserve is melted down to produce one gigantic ingot, which is then encased in steel. However, when Diabolik successfully steals the ingot he discovers that it has been made radioactive.

Wearing a protective suit and helmet, he starts melting it down in his underground hideout. With the police hot on Diabolik’s radioactive tail, the ingot suddenly explodes and covers him with molten gold, turning Diabolik into a statue. His gilded figure is left on display and Eva visits it before she is arrested as an accomplice. What seems to have been an anti-climax still manages to end on a high note when Eva sees the statue wink at her, proving that Diabolik has ultimately outwitted his adversaries again. That’s where the film abruptly finishes, leaving an eager audience waiting for a sequel that would never happen. Soon after Danger: Diabolik was completed, shooting began on Barbarella, which led to the recycling of some sets, like Valmont’s nightclub. Bava described the filming as ‘nightmarish’ and said that De Laurentiis forced him to tone down the violent scenes in the film. De Laurentiis wanted a family-friendly film with a charming thief, while Bava wanted to be more faithful to the original comics.

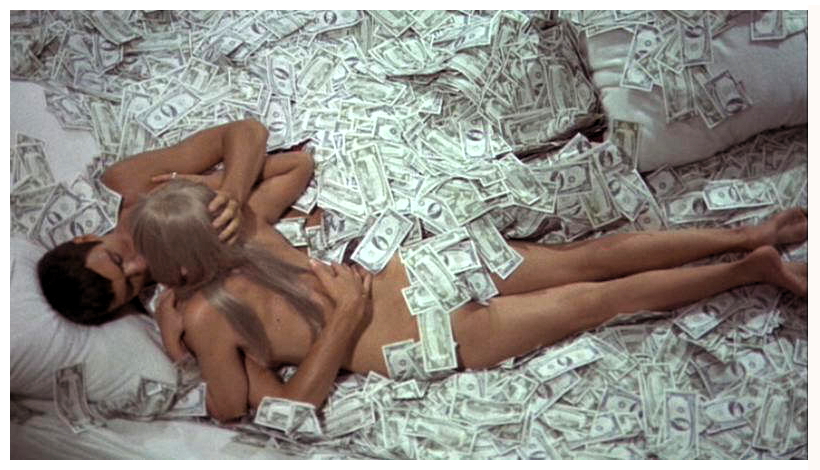

Bava’s superb visual sense is ideal for this comic-strip adventure, which looks like a brilliant homage to sixties spy movies almost to the point of garishness, the very definition of European pulp. The trouble here is pacing (the scenes featuring Terry-Thomas are supposed to be amusing but just drag), static writing, and some of the worst blue-screen chromakey work I’ve ever seen. The film is certainly colourful and definitely tongue-in-cheek – at one point, for instance, Diabolik and Eva make love in a huge soft nest of bank notes. Bava brought the film in well under budget, so De Laurentiis offered him the job of directing the sequel, but Bava vowed never to work with the producer ever again, and the project was shelved indefinitely. It was the combined commercial success of Danger: Diabolik and Barbarella that set De Laurentiis on the wrong path, towards brightly-coloured comic-strip action seasoned with parody, and the implementation of special effects that make little effort to look like anything realistic.

His prime crime with both King Kong (1976) and Flash Gordon (1980) was not taking the subject matter seriously enough. In both cases his directors were given a screenplay by Lorenzo Semple Jr who wrote the very funny, very camp Batman television series in the sixties and Doc Savage (1975). Admittedly, no one on Earth writes quite like Semple, but the illusion of reality is central for lovers of fantastic fiction, they don’t want to be constantly reminded that they’re watching a fiction. Semple’s insistence on parody has the effect of making the stories seem unreal. Nevertheless, I can’t help but wonder what his draft of De Laurentiis’s Dune (1984) looked like, but that’s another story for another time. It’s on this note I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have another opportunity to simultaneously raise both hackles and cackles with more dreadful dross from the drains of Los Angeles in another trouser-moistening fear-filled film review for…Horror News! Toodles!

Danger: Diabolik (1968)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews