Plastic skeletons dangling on wires above the audience! Theatre seats wired to buzz the audience! Fright-breaks giving cowardly customers a chance to escape to the lobby! Insurance policies guaranteeing audience members against death by fright! These and other outrageous gimmicks designed to pull in more moviegoers may seem like the creations of a P.T. Barnum rather than a directorial master of suspense and terror. In fact, they’re the creations of a man who is a bit of both – a filmmaker with the soul of a carnival pitchman whose goal was to scare the pants off America. It’s a matter of debate whether the films he made lived up to that goal, but there’s no denying that the delightful promotional schemes he came with made teenagers in the fifties and sixties step right up in droves, and made him one of the most beloved figures in the history of cinema. A true king when it came to horror-movie hype. His name? William Castle.

In his autobiography Step Right Up I’m Gonna Scare The Pants Off America, the so-called King Of The Gimmicks said he got hooked on horror at very early age, when his parents took him to see a Broadway play called The Monster. It was then and there that the young William Schloss decided to become an actor. He changed his surname to its English equivalent and made his stage debut while barely in his teens. Castle abruptly decided to change careers and work behind the scenes instead. The opportunity came in 1929 when his idol, Bela Lugosi, tapped him to become the assistant stage manager for a road company tour of the play Dracula. In 1939 Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures brought William Castle to Hollywood and put him to work as a dialogue coach.

Castle quickly learned the techniques of film-making and made his directorial debut with a movie entitled Chance Of A Lifetime (1943). It was an entry in the studio’s popular Boston Blackie detective franchise starring Chester Morris. The following year Castle directed Richard Dix in the first installment of a new detective franchise for the studio entitled The Whistler (1944). Over the next decade Castle made three more films in the series, as well as a number of gangster pictures, westerns and costume dramas for Columbia and other studios. By 1954 Castle had tired of being a contract director moving from one studio assignment to another. He wanted to work for himself, to make his own films for his own company. He wanted to be a showman. Launching out on his own was a risky business. He needed something sure, and he found it, in a French picture that was setting box-office records everywhere, entitled Diabolique (1955).

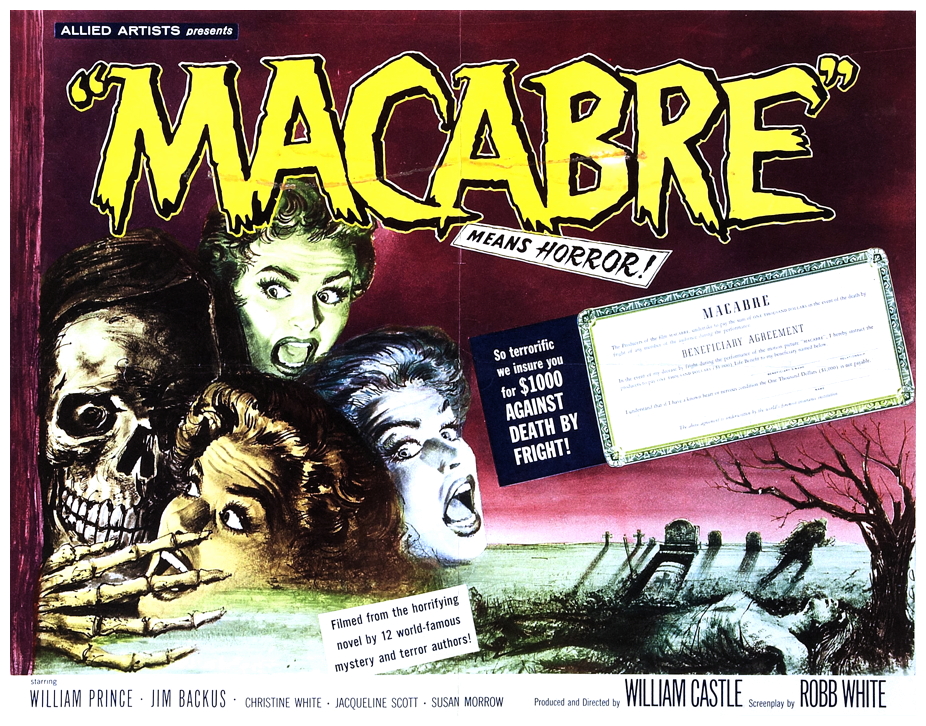

“There were lines all around the block. I decided then and there that if a foreign horror picture with English subtitles could draw such a huge crowd, think of what an all-English-speaking picture would do!” Castle found a story that combined Diabolique’s crowd-pleasing ghoulishness, suspense and unexpected plot twists, in a 1951 novel called The Marble Forest written by Anthony Boucher under the pseudonym Theo Durrant. Castle snapped up the rights to the book, and brought in Rob White to adapt it. Castle and White financed the film’s US$90,000 budget themselves, and gave it a more French-sounding title. Macabre (1958) was their first film together, a very low budget movie that was a big hit, and they continued to work together over the years, basically because it was profitable and it worked. To convince customers that Macabre was the most frightening movie ever made, Castle persuaded Lloyd’s Of London to insure each ticket-buyer for US$1000 in the event of death by fright. The gimmick worked like a charm. The film was a huge hit, paving the way for more shockers with even more outrageous gimmicks.

Castle had turned his career totally around. For many years he was a minor B-grade movie director who did anything that was handed to him but, after Macabre became a hit followed by House On Haunted Hill (1959), there was absolutely no stopping him. A throwback to the Old-Dark-House type of thriller that had captivated him in his youth, Castle devised ‘Emergo‘ for House On Haunted Hill. Emergo was an early prototype of a truly holographic 3-D movie process that wouldn’t require the audience to wear silly glasses. Emergo was a simple motion path generator consisting basically of a plastic skeleton on a wire. There’s a point in the film when the skeleton would be pushed out from the top of the screen along a wire above the heads of the audience. They stopped it when kids kept shooting at the skeleton with BB guns. The kids would go berserk and they’d tear the place apart, but Castle didn’t care, it wasn’t his theatre. He still got paid.

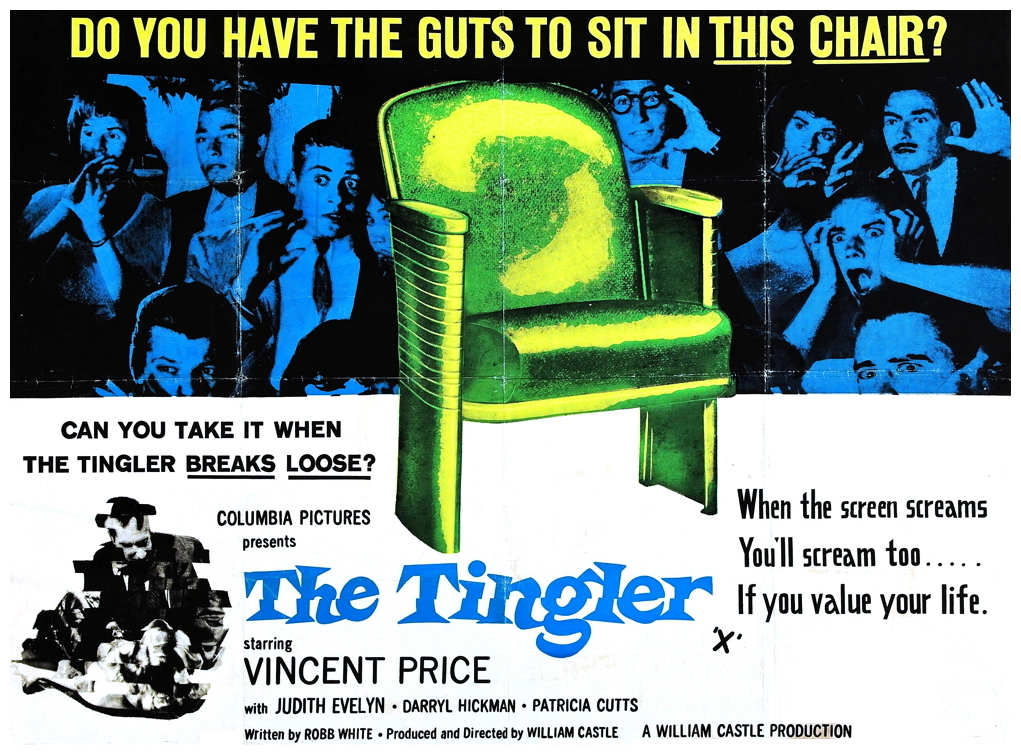

Castle moved back to Columbia to make his next series of shockers, the first of which was The Tingler (1959). For this film the director had theatre seats electrically wired to give audiences a buzz, a gimmick he ballyhooed in the film’s advertising as ‘Percepto‘. At a certain point in the film the theatre lights go out entirely and, in absolute darkness, all the audience can hear is Vincent Price‘s panicked voice: “Scream! Scream for your lives! The Tingler is loose in this theatre!” It was just wonderful and, of course, if you were a kid you just go along with it – audience members would stand on their seats and start screaming and yelling. If you were lucky, the creature was scared away and the movie was allowed to continue. Publicity stated that people were actually shocked by electricity while watching The Tingler, even William Castle said as much, but it was just another gimmick to hide another gimmick. What he actually had were tiny motors not unlike clockwork joy-buzzers that vibrated the bottom of the seat. But they never actually shocked anyone, that would have been taking things too far.

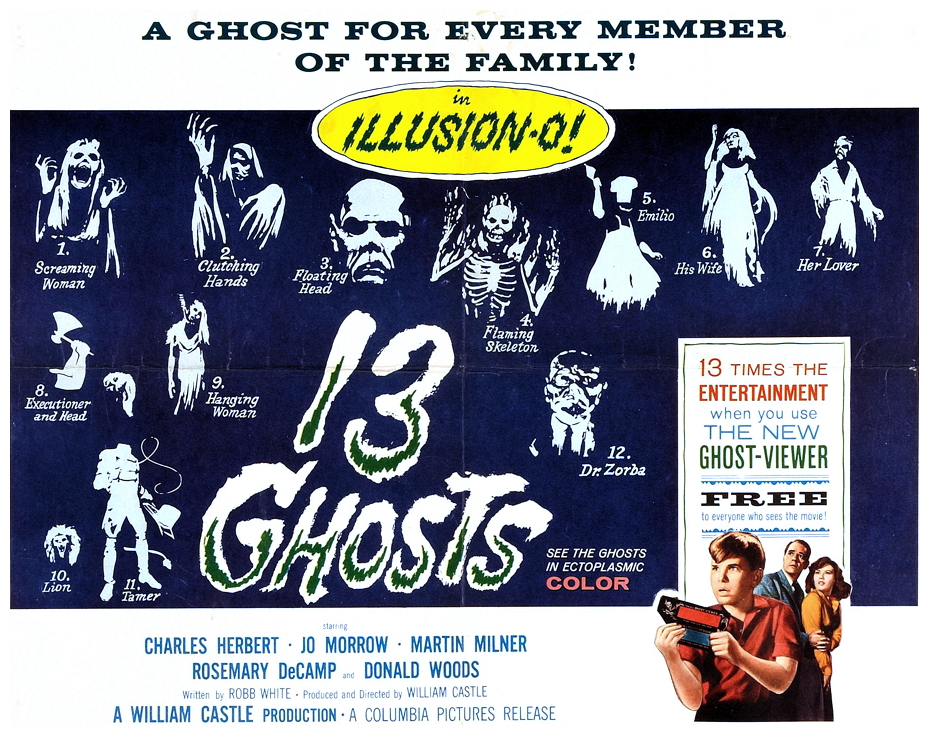

For 13 Ghosts (1960) Castle concocted ‘Illusion-O‘ which allowed audiences to see the movie’s otherwise invisible title characters by putting on special glasses supplied at the box-office. Many people assumed that the film was in 3-D because of these viewers, but it’s not the case. Castle did something with infrared light, and if you put the viewer up to your eyes when they say so – when the ghosts are coming – you could see the ghosts better. Alternatively you could use the other colour lenses which completely obliterated the image from the screen. If you didn’t use the viewer at all you could kind-of see them anyway. For Mr. Sardonicus (1961) Castle appeared at the climax to conduct a ‘Punishment Poll‘ that allowed audiences to vote thumbs-up or thumbs-down on the fate of the villain. At a certain point in the movie Castle comes on screen and states that it is now time to vote on the fate of Mr. Sardonicus. Everyone held up their cards thumbs-up or thumbs-down, and Castle is on the screen pretending to count them. Everyone would start booing, of course, because it became pretty clear that he had only ever filmed the one ending.

For Zotz! (1962), each ticket-buyer was given a replica ‘magic’ coin, and 13 Frightened Girls (1963) featured a highly-publicised international hunt for a baker’s dozen of the prettiest girls in the world. So it would seem odd that his next film, a remake of The Old Dark House (1963), would feature absolutely no gimmicks whatsoever. Castle wanted gimmicks, yes, but such marketing tomfoolery would not be tolerated by co-producer Anthony Hinds, the son of the founder of Hammer Films. For Strait-Jacket (1964) Castle created the much imitated ad-line “Just Keep Telling Yourself It’s Only A Movie.” For other films Castle had nurses stationed in theatre lobbies handing out bogus nerve-steadying pills to the weak-of-heart, and he often acted as an usher who helped screaming patrons find the nearest exit. Most of these people were planted in the audience by Castle himself of course. Castle appeared on screen to introduce his films and took centre-stage in the coming attractions too.

He also promoted the creation of his own fan club. By 1963, the club’s newsletters announcing upcoming Castle movies and bearing his famous silhouette, were being mailed out to more than 250,000 card-carrying members. One of them was young Joe Dante who grew up to be a genre director himself, and paid tribute to his idol in his film Matinee (1993): “Matinee has a character in it sort-of based loosely on William Castle, and the thing we were trying to communicate about this guy is that he knows that movies are supposed to be fun and he knows that when you go to a horror picture, you’re exorcising some kind of stuff that’s inside you and making it feel okay. In fact there’s a scene in the movie when he walks down the street and explains to a kid why he makes these horror movies, and it’s sort of a little distillation of my feeling about the place these movies have in people’s lives. Certainly in mine.”

Check out: William Castle – Tribute and Historical Overview (Part 2)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Great part 1! Dense with entertaining information that makes you wish you could have experienced Castle at work first hand.

Thanks for reading! This article was the first in a series. There was a DVD with several William Castle films released at that time, and Horror News asked for a review for each film. I got there eventually – these were not amongst his best – 13 Frightened Girls (1963) was one of them – but don’t be surprised if I’ve doubled up on some information.