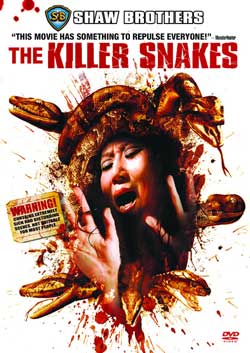

SYNOPSIS:

A young man who has been beaten, abused, humiliated and laughed at all his life finds that he has an unusual empathy with snakes. He can talk to them and they understand him, and eventually he finds that he can get them to do his bidding. He decides to use his newfound friends to take his revenge on everyone who ever did him wrong

REVIEW:

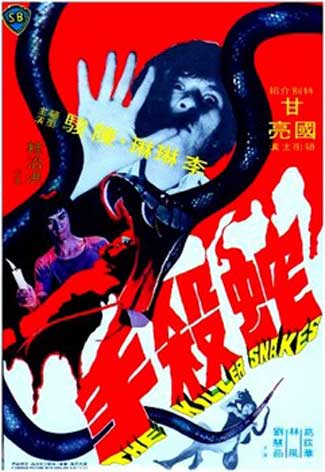

Here we have a bizarre little curio from Hong Kong, with an obligingly obvious title that promises good old-fashioned trashy fun. The obvious comparison to make is with Snakes on a Plane, or with the various ‘killer animals’ features over the years that hit a high with The Birds and a low with The Swarm. While these comparisons are certainly valid, there’s a little more to The Killer Snakes (original title She Sha Shou) than at first meets the eye.

The basic premise is easily summed up. A bullied and downtrodden young misfit, who has a mysterious power over snakes, decides to get revenge when the local Tong mobsters kidnap the girl he loves from afar. This revenge involves snakes, surprisingly enough. The plot follows the well-trodden path from wretchedness to empowerment to vindication, as seen in countless films from The Karate Kid to The Toxic Avenger, but it also takes us to some exceedingly strange and disturbing places along the way.

The Killer Snakes has some of the dusty charm of seventies b-movies—I could easily imagine it being featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000—and much of the appeal is because of its flaws as well as in spite of them. On one level it’s simply a cheap exploitation film, but it also has hidden depths. Most notably, it illustrates the causal link between suffering abuse and becoming an abuser, and shows a psychological complexity rare in films of its kind.

One of the first things I noticed early on in this film is its tendency to set up expectations and then knock them down. The protagonist Keto (Kwok-Leung Gan) initially appears to be a loveable, bumbling hero in the Jackie Chan mould, but it becomes gradually clear that he is something quite different. His awkward, tentative lechery at first seems harmless (at least in that seventies Benny Hill way that certainly wouldn’t be acceptable nowadays), but it soon transpires that his proclivites are even more unwholesome than might have been suspected.

Barely ten minutes into the film we are treated to the sight of him writhing on the floor of his squalid living quarters, staring up at the P*rnographic photos tacked to his ceiling, licking his lips and groaning at the saditic fantasies playing in his head. The fantasies aren’t confined to his head, either, but are shown in garish montages superimposed over his sweating, gurning face. It only gets worse from there.

The bad guys are the typical cartoonish Tong members you’ve seen in a thousand kung fu films, and while their leader is the ostensible bad guy in this film, there is not much to him. He is only there to occupy the role of the antagonist in the narrative, because the real bad guy is unquestionably Keto himself. He’s not so much ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ as ‘Hyde and even more Hyde’, and it’s almost impossible for the viewer to really sympathise with him. The closest analogue I can think of is the titular character from George A. Romero’s Martin; a protagonist from whom you remain detatched, while maintaining a horrified curiosity in what will happen to him.

The most horrifying moments in the film all belong to Keto, not least whenever his victim is a woman. Even when he is trying to play the heroic role, he is a monster. For instance, after the bad guys kidnap the girl he loves in order to force her into prostitution, he is understandably anxious to find her. In an effort to ascertain her whereabouts, he kidnaps one of the Tong prostitutes, strips her naked, and ties her up to be eaten alive by two monitor lizards. The sight of the lizards’ blood-smeared muzzles is nothing compared to the look on Keto’s face, amused and titillated by what he has engineered.

With regard to the damsel-in-distress narrative, I’m sure it won’t spoil this film if I reveal that there is no cop-out happy ending, no Hollywood redemption. This is a film about the consequences of cruelty, and about the hypocrisy of the male desire to protect and possess women. On another level, however, it’s a good slice of Hong Kong schlock, and it is just as enjoyable as a standard example of its idiom.

The Killer Snakes (1975)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews