SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

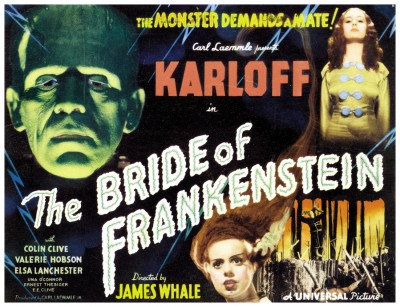

“Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein Or The Modern Prometheus, reveals to Percy Shelley and Lord Byron that Henry Frankenstein and his Monster did not die. Both lived, and went on to even stranger misadventures than before. As the new story begins, Henry wants nothing more than to settle into a peaceful life with his new bride. But his old professor, the sinister Doctor Pretorius, now disgraced, appears unexpectedly. Eventually, he and the Monster blackmail him into continuing his work. The Monster wants his creator to build him a friend, and Pretorius wants to see dead tissue become a living woman. Henry is forced to give his creature a bride.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Mary Shelley‘s original story of Frankenstein Or The Modern Prometheus has never really received an adequate screen treatment. In Frankenstein (1931), the least excusable change was to have the brain of a lunatic put into the skull of the artificial man, thus giving an all-too-obvious reason for his eventual homicidal behaviour, which would be more interesting if seen as resulting from the painful injuries to his innocence. The director, James Whale, was then mainly known for his work on the stage. A highly intelligent man, he made the most of this, his third film and first horror piece and, to his dismay, became typecast as Hollywood’s top horror director. The film also made a star out of bit-player Boris Karloff, who was tested for the part only after Bela Lugosi had turned it down. The film was made to cash-in on the success of Dracula (1931), also by Universal, and Lugosi’s rejection of the role was the first of many disastrous decisions he was to make in his tragically second-rate career. Karloff, on the other hand, soared to prominence on the basis of this one film, and stayed there ever after.

Filmed with admiral restraint, Frankenstein has moments of uncanny effectiveness even today, notably the creature’s first gradual appearance, and the later scene where he drowns the little girl. Unfortunately, early censorship concealed the fact that the drowning was accidental, thus the one scene that displayed the creature’s pristine innocence was destroyed. This innocence was better portrayed in the sequel Bride Of Frankenstein (1935) which, on the whole, remains the best of the Frankenstein films. It too was directed by Whale and starred Karloff, and is surpassed only by King Kong (1933) among the all-time best monster movies. Not even Kong had this much class, considering that it contains bristling philosophical discourse between intellectual giants Doctors Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), and even the monster engages in smart conversation (his forty-four-word vocabulary came from the test papers of Universal Studio‘s child actors) while listening to classical music, drinking wine and smoking a fine cigar.

Filmed with admiral restraint, Frankenstein has moments of uncanny effectiveness even today, notably the creature’s first gradual appearance, and the later scene where he drowns the little girl. Unfortunately, early censorship concealed the fact that the drowning was accidental, thus the one scene that displayed the creature’s pristine innocence was destroyed. This innocence was better portrayed in the sequel Bride Of Frankenstein (1935) which, on the whole, remains the best of the Frankenstein films. It too was directed by Whale and starred Karloff, and is surpassed only by King Kong (1933) among the all-time best monster movies. Not even Kong had this much class, considering that it contains bristling philosophical discourse between intellectual giants Doctors Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), and even the monster engages in smart conversation (his forty-four-word vocabulary came from the test papers of Universal Studio‘s child actors) while listening to classical music, drinking wine and smoking a fine cigar.

Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein, but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, Bride Of Frankenstein is a reflection of Whale himself, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror. A more superior offering than the first film, the sequel really brings the monster to life. It is Karloff’s performance that makes this film great. Almost hidden behind Jack Pierce‘s remarkable makeup, his sensitive eyes still come through, expressing the monster’s feelings, like a stray dog beaten, burned and paranoid, yet desperate for kindness.

Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein, but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, Bride Of Frankenstein is a reflection of Whale himself, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror. A more superior offering than the first film, the sequel really brings the monster to life. It is Karloff’s performance that makes this film great. Almost hidden behind Jack Pierce‘s remarkable makeup, his sensitive eyes still come through, expressing the monster’s feelings, like a stray dog beaten, burned and paranoid, yet desperate for kindness.

Bride Of Frankenstein displays a delicate balance between black comedy and all-out horror. In an ironic prologue Elsa Lanchester plays young author Mary Shelley – frightened of thunder, fearful of the dark – explaining to her Lord Byron and her husband how the monster escaped the conflagration at the end of the previous film. “That wasn’t the end at all…” cuts almost directly to a gloating Una O’Connor saying, “Insides are always the last to be consumed,” and then to the creature’s unexpected reappearance. Whale displays a bold macabre sense of humour throughout – just see what happens to a silly farm wife and a beautiful sheepherder – and he also has fun with the angular faces of his four stars, shooting them in tremendous close-ups, often using wild camera angles.

Bride Of Frankenstein displays a delicate balance between black comedy and all-out horror. In an ironic prologue Elsa Lanchester plays young author Mary Shelley – frightened of thunder, fearful of the dark – explaining to her Lord Byron and her husband how the monster escaped the conflagration at the end of the previous film. “That wasn’t the end at all…” cuts almost directly to a gloating Una O’Connor saying, “Insides are always the last to be consumed,” and then to the creature’s unexpected reappearance. Whale displays a bold macabre sense of humour throughout – just see what happens to a silly farm wife and a beautiful sheepherder – and he also has fun with the angular faces of his four stars, shooting them in tremendous close-ups, often using wild camera angles.

Whale’s stroke of genius was to cast Elsa Lanchester in a second role, as the artificial woman who is to be a mate for the creature created from cadavers out of rifled graves. Lanchester, who beat out Brigette Helm and Phyllis Brooks for the role, is marvelous in her brief appearance as the Bride, in a white shroud on stilts almost a metre high that make her movements almost bird-like, her hairstyle inspired by Nefertiti. The moment she is brought to life is one of the great climaxes of cinema history, set in a towering laboratory with elaborate electronic apparatus (designed by Kenneth Strickfaden) hissing and spluttering. There is the horrified scream with which she first greets the monster: Her wild-eyed weirdly coiffeured appearance; the inhuman mechanical jerking of her neck as she turns her head; the guttural hiss like a maddened cat as the creature prepares to pull the lever that will destroy them all. This is an extraordinary piece of scene-stealing particularly because, although bizarre, the Bride is surprisingly sexy.

Whale’s stroke of genius was to cast Elsa Lanchester in a second role, as the artificial woman who is to be a mate for the creature created from cadavers out of rifled graves. Lanchester, who beat out Brigette Helm and Phyllis Brooks for the role, is marvelous in her brief appearance as the Bride, in a white shroud on stilts almost a metre high that make her movements almost bird-like, her hairstyle inspired by Nefertiti. The moment she is brought to life is one of the great climaxes of cinema history, set in a towering laboratory with elaborate electronic apparatus (designed by Kenneth Strickfaden) hissing and spluttering. There is the horrified scream with which she first greets the monster: Her wild-eyed weirdly coiffeured appearance; the inhuman mechanical jerking of her neck as she turns her head; the guttural hiss like a maddened cat as the creature prepares to pull the lever that will destroy them all. This is an extraordinary piece of scene-stealing particularly because, although bizarre, the Bride is surprisingly sexy.

The film is made even more baroque by the uneasy camerawork (which gives the impression of fluidity even though there are very few tracking shots) and by the inclusion of a new character, a genuine Mad Scientist this time. Doctor Pretorius is a grimacing sardonic figure: “Do you like gin? It’s my only weakness. The creation of life is enthralling! Enthralling, is it not?” Arguably, his inclusion may be the film’s only weakness. Played too obviously for laughs, he weakens the audience’s commitment to the story as believable, especially in the scene where he reveals his homunculi: The little king, queen, bishop and others he has grown from seeds and keeps in bottles.

The film is made even more baroque by the uneasy camerawork (which gives the impression of fluidity even though there are very few tracking shots) and by the inclusion of a new character, a genuine Mad Scientist this time. Doctor Pretorius is a grimacing sardonic figure: “Do you like gin? It’s my only weakness. The creation of life is enthralling! Enthralling, is it not?” Arguably, his inclusion may be the film’s only weakness. Played too obviously for laughs, he weakens the audience’s commitment to the story as believable, especially in the scene where he reveals his homunculi: The little king, queen, bishop and others he has grown from seeds and keeps in bottles.

There are many reasons the sequel is better than the original, not least that it deals with the Monster’s need for female companionship, which is central to the second-half of Shelley’s novel. It is not cold, bleak or depressing like the original, has a bigger budget and the production values breathe life into the story. The claustrophobic castle and laboratory sets are balanced by spacious candlelit chambers with shiny floors and columns, all covered with shadows, and the expressionistic forest is wonderful sight to behold. Neither Whale nor his cameraman John Mescall strove for realism – this film was always meant to be a visualisation of a story.

There are many reasons the sequel is better than the original, not least that it deals with the Monster’s need for female companionship, which is central to the second-half of Shelley’s novel. It is not cold, bleak or depressing like the original, has a bigger budget and the production values breathe life into the story. The claustrophobic castle and laboratory sets are balanced by spacious candlelit chambers with shiny floors and columns, all covered with shadows, and the expressionistic forest is wonderful sight to behold. Neither Whale nor his cameraman John Mescall strove for realism – this film was always meant to be a visualisation of a story.

An essay in the purely fantastic, Bride Of Frankenstein is one of the few genuine classics of the genre. It has many bold moments: The subdued references to the Christ’s crucifixion; the wedding bells on Franz Waxman‘s soundtrack as the Bride comes to life; the use of lightning to symbolise both the potency and the unpredictability of science. Universal made at least five sequels to these first two films, all of which were uniformly disappointing. Karloff only starred in the first of these, Son Of Frankenstein (1939). The last one, a lunatic parody entitled Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), is surprisingly the best of an inferior bunch. Bud and Lou were in top form, and Universal saw them as the perfect vehicle to milk more profit from their creaky monsters.

An essay in the purely fantastic, Bride Of Frankenstein is one of the few genuine classics of the genre. It has many bold moments: The subdued references to the Christ’s crucifixion; the wedding bells on Franz Waxman‘s soundtrack as the Bride comes to life; the use of lightning to symbolise both the potency and the unpredictability of science. Universal made at least five sequels to these first two films, all of which were uniformly disappointing. Karloff only starred in the first of these, Son Of Frankenstein (1939). The last one, a lunatic parody entitled Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), is surprisingly the best of an inferior bunch. Bud and Lou were in top form, and Universal saw them as the perfect vehicle to milk more profit from their creaky monsters.

While the comedy is deft and precisely timed, the studio made sure not to mock the monsters themselves. Already seen as remnants of a bygone era (just seventeen short years after the the original Dracula and Frankenstein were released in 1931), Universal still treated them with the respect they deserved. For one last time, the classic monsters got to bask in the applause of appreciative audiences. It’s with that thought in mind I’ll graciously invite to please join me again next week when I have another opportunity to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl with another lusting, slashing, ripping flesh-hungry, blood-mad massacre from the back side of…Horror News! Toodles!

While the comedy is deft and precisely timed, the studio made sure not to mock the monsters themselves. Already seen as remnants of a bygone era (just seventeen short years after the the original Dracula and Frankenstein were released in 1931), Universal still treated them with the respect they deserved. For one last time, the classic monsters got to bask in the applause of appreciative audiences. It’s with that thought in mind I’ll graciously invite to please join me again next week when I have another opportunity to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl with another lusting, slashing, ripping flesh-hungry, blood-mad massacre from the back side of…Horror News! Toodles!

Bride Of Frankenstein (1935) is now available on Blu ray per Universal Studios on the “Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection”

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews