SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Salem’s Lot is a town which a new member, Mr. Straker, has taken as his new ‘home’, and has a mysterious partner, namely Mr. Barlow. Not too long after Straker arrives in Salem’s Lot, people start disappearing from sight and dying from odd causes, and no one is sure why, including Ben Mears who is in town to write a new book on the town’s rumored haunted house called the Marsten House, which overlooks the town and hides a terrible secret about to be unleashed.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

There seems to be a general, if undiscussed, agreement among filmmakers that vampires are more refined and cultured than werewolves and infinitely more presentable than zombies. This is a little strange because, like zombies, vampires are undead (which is quite different to being alive) and, like werewolves, they symbolise the ravenous beast within. Indeed, Christopher Lee’s Dracula (1958) specialised in animal snarls and bestial hisses and, in the original Nosferatu (1922), Max Schreck looked more like a rodent than a human.

1979 was a big year for vampires. At the Hollywood end of the spectrum, Universal Studios attempted to reboot their romantic horror franchise with a lavish retelling of Stoker’s classic Dracula (1979) starring a young Frank Langella making a convincing vampire, all urbane wit, charm and well-mannered sexiness when at ease, a ferocious beast when aroused. At the intellectual end of the spectrum was a German film directed by Werner Herzog, Nosferatu The Vampyre (1979), a beautiful dream-like remake of Nosferatu. For surprisingly long stretches of the film, Herzog submerges his own characteristic concerns in a loving recreation of Murnau’s imagery, now in colour and sound, with the death-yearning Klaus Kinski accurately made up to look like Max Schreck.

1979 was a big year for vampires. At the Hollywood end of the spectrum, Universal Studios attempted to reboot their romantic horror franchise with a lavish retelling of Stoker’s classic Dracula (1979) starring a young Frank Langella making a convincing vampire, all urbane wit, charm and well-mannered sexiness when at ease, a ferocious beast when aroused. At the intellectual end of the spectrum was a German film directed by Werner Herzog, Nosferatu The Vampyre (1979), a beautiful dream-like remake of Nosferatu. For surprisingly long stretches of the film, Herzog submerges his own characteristic concerns in a loving recreation of Murnau’s imagery, now in colour and sound, with the death-yearning Klaus Kinski accurately made up to look like Max Schreck.

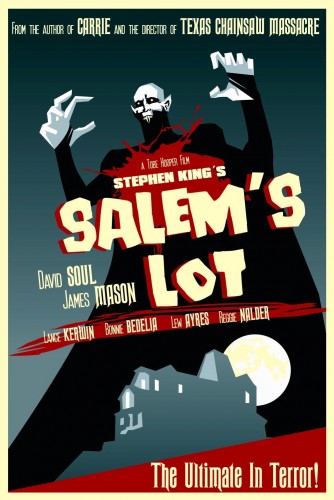

Less interestingly, the same Schreck makeup appeared in quite a different vampire story, the two-part television miniseries Salem’s Lot (1979) based on the bestselling novel by Stephen King. Released theatrically outside the USA, the film’s running time was around 112 minutes but, if you insist on inflicting this somewhat dodgy adaptation upon yourself, I recommend you to seek out the complete 184 minute version, which should greatly enrich your perspective of the plot.

Less interestingly, the same Schreck makeup appeared in quite a different vampire story, the two-part television miniseries Salem’s Lot (1979) based on the bestselling novel by Stephen King. Released theatrically outside the USA, the film’s running time was around 112 minutes but, if you insist on inflicting this somewhat dodgy adaptation upon yourself, I recommend you to seek out the complete 184 minute version, which should greatly enrich your perspective of the plot.

Horror fans were eager to see this, for it was directed by Tobe Hooper, of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1973) fame. Richard Kobritz, producer of the suspenseful and acclaimed John Carpenter made-for-television movie Someone’s Watching Me (1978), handpicked Mr. Hooper to direct Salem’s Lot, which had been in development for quite some time already with The Exorcist (1973) director William Friedkin briefly attached as producer.

Horror fans were eager to see this, for it was directed by Tobe Hooper, of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1973) fame. Richard Kobritz, producer of the suspenseful and acclaimed John Carpenter made-for-television movie Someone’s Watching Me (1978), handpicked Mr. Hooper to direct Salem’s Lot, which had been in development for quite some time already with The Exorcist (1973) director William Friedkin briefly attached as producer.

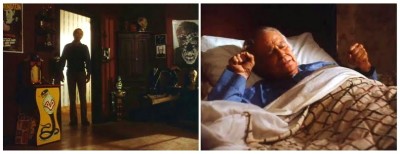

Salem’s Lot became Hooper’s most polished and mainstream film to date, but the deadening propriety of television took its toll, and there isn’t much left that’s terribly disturbing, although one or two TV taboos are mildly contravened: Children are placed in jeopardy – there is an excellently creepy vampire, a small boy, who floats outside his brother’s bedroom window with a very nasty smile – and, in an entirely non-fantastic scene, a cuckolded man takes humiliating revenge on his wife’s lover. In fact, this is the most typically Hooper sequence – it has all the sordid sweatiness of real human fear, and it makes the vampire sequences look a bit hollow in comparison.

Salem’s Lot became Hooper’s most polished and mainstream film to date, but the deadening propriety of television took its toll, and there isn’t much left that’s terribly disturbing, although one or two TV taboos are mildly contravened: Children are placed in jeopardy – there is an excellently creepy vampire, a small boy, who floats outside his brother’s bedroom window with a very nasty smile – and, in an entirely non-fantastic scene, a cuckolded man takes humiliating revenge on his wife’s lover. In fact, this is the most typically Hooper sequence – it has all the sordid sweatiness of real human fear, and it makes the vampire sequences look a bit hollow in comparison.

Although supported by an experienced cast of character actors (Lance Kerwin, Geoffrey Lewis, Lew Ayres, Elisha Cook Junior, amongst others), David Soul makes an extremely colourless hero in a predictably wet bit of television casting. Unable to shake his seventies persona of Hutch from Starsky And Hutch, Mr. Soul moved to London in the nineties, forging a brand new career in live theatre, and became a British citizen in 2004. He appeared as himself in the first season of the comedy sketch show Little Britain, and co-starred with David Suchet and James Fox in Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Death On The Nile (2004). It was about this time that Mr. Soul was also a guest on the popular BBC car show Top Gear, and almost became the show’s fastest driver but, somehow, he managed to break the car’s gearbox just before the finish line.

Although supported by an experienced cast of character actors (Lance Kerwin, Geoffrey Lewis, Lew Ayres, Elisha Cook Junior, amongst others), David Soul makes an extremely colourless hero in a predictably wet bit of television casting. Unable to shake his seventies persona of Hutch from Starsky And Hutch, Mr. Soul moved to London in the nineties, forging a brand new career in live theatre, and became a British citizen in 2004. He appeared as himself in the first season of the comedy sketch show Little Britain, and co-starred with David Suchet and James Fox in Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Death On The Nile (2004). It was about this time that Mr. Soul was also a guest on the popular BBC car show Top Gear, and almost became the show’s fastest driver but, somehow, he managed to break the car’s gearbox just before the finish line.

Unfortunately, the one really inspired bit of casting didn’t quite work out. Hollywood veteran James Mason practically sleeps through his role of the Renfield-like Mr. Straker. One can easily imagine Mr. Mason finishing every scene with the words, “Can I have my cheque now please?” Speaking of which, since the early seventies, Mr. Mason has always worked contractual clauses guaranteeing bit parts for his wife, Australian actress Clarissa Kaye. We’ve seen Mr. Mason enjoying much better times in such films as Odd Man Out (1947), 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954), Journey To The Centre Of The Earth (1959), Lolita (1962), Age Of Consent (1969), Frankenstein The True Story (1973), Heaven Can Wait (1978), The Boys From Brazil (1978), Murder By Decree (1979), Yellowbeard (1983), and his extraordinary final film role as Doctor Fischer Of Geneva (1985).

Unfortunately, the one really inspired bit of casting didn’t quite work out. Hollywood veteran James Mason practically sleeps through his role of the Renfield-like Mr. Straker. One can easily imagine Mr. Mason finishing every scene with the words, “Can I have my cheque now please?” Speaking of which, since the early seventies, Mr. Mason has always worked contractual clauses guaranteeing bit parts for his wife, Australian actress Clarissa Kaye. We’ve seen Mr. Mason enjoying much better times in such films as Odd Man Out (1947), 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954), Journey To The Centre Of The Earth (1959), Lolita (1962), Age Of Consent (1969), Frankenstein The True Story (1973), Heaven Can Wait (1978), The Boys From Brazil (1978), Murder By Decree (1979), Yellowbeard (1983), and his extraordinary final film role as Doctor Fischer Of Geneva (1985).

Despite its all-too-obvious problems, the 1979 adaptation of Salem’s Lot looks like a classic when compared to the 2004 remake written by Peter Filardi, whose only real hit was Flatliners (1990) fourteen years before. Bottom line? Read the original novel instead – neither film version is able to capture the all-embracing quality of Mr. King’s excellent story in which an entire town is convincingly destroyed. Now, having demonstrated to you the perils of probing the dark depths of Hollywood, I’ll vanish into the night, after first inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Despite its all-too-obvious problems, the 1979 adaptation of Salem’s Lot looks like a classic when compared to the 2004 remake written by Peter Filardi, whose only real hit was Flatliners (1990) fourteen years before. Bottom line? Read the original novel instead – neither film version is able to capture the all-embracing quality of Mr. King’s excellent story in which an entire town is convincingly destroyed. Now, having demonstrated to you the perils of probing the dark depths of Hollywood, I’ll vanish into the night, after first inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![True_Blood_Jessica_Fangs_by_Morgadu[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/True_Blood_Jessica_Fangs_by_Morgadu1-310x165.jpg)

I could not disagree more with Nigel Honeybone’s assessment of Salem’s Lot (1979). David Soul could not have been a better choice for the role of Ben Mears. He met the challenge of projecting the image of an emotionally guarded and evasive personality with a mystically intuitive if not obsessive connection to an old house. Being the son of a minister, being of Norwegian descent, and having a very mature face buttresses Soul’s efforts to convince viewers to suspend disbelief in what is a rather fantastical premise. Soul’s credibility plays no small part in why we buy into vampires. This credibility is put on full display throughout his continuous goading of Dr. Norton, who I suspect serves as a personification of audience skepticism. His restrained startle reaction when Mark Petrie (Lance Kerwin) approaches him from behind in the climactic scene of the film is a skillful piece of acting.

Contrary to your depiction of a mail-in-job by veteran actor James Mason, I found his delivery thoughtfully and provocatively nuanced. Reports indicate that Mason’s wife, who is also cast in the film as Marjorie Glick, helped to stoke his interest in the role. One of my favorite images of the film is one in which Straker projects disengages from Ben Mears when Mears is prodding him about his interest in the Marsden house — what is likely some blend of disinterest and evasiveness. Afterall, what would the thoughts of this man matter to Straker when Straker expects this person like all the others in the town to within a matter of days be among the undead?

I also disagree with your assessment of the impact of television’s “deadening propriety.” Television pressured the makers of Salem’s Lot to rely less on gore and more on atmosphere, the outcome of which is an overtone of the grave throughout the miniseries. I cannot imagine another horror film that has left a generation of young viewers with quite as many and quite as enduring images of horror. When seeing a number of these vampires for the first time, the drop off from initial startle to enduring dread is not all that steep and I have read many accounts of viewers having reported what I would describe as an acute and a chronic form of residue — from not being able to leave the light on in the bedroom for weeks to flashbulb memories over the ensuing decades of romantically dreadful and nostalgiac imagery connecting them to their childhood. Indeed the effects of this film are almost PTSD-like. Even between vampire scenes, director Hooper stirs the depths of your soul with such images as shadows of passing clouds over the mid-day facade of the Marsden House as seen through the upward-looking eyes of Susan Norton. No film better captures the essential purity of the Unholy and instills a viewers a feeling of what it means to experience a state of being that lacks all transcendental aspects. The film strips away layers of civilized sensibilities and rational comfort almost imperceptibly instilled in us over years of learning to share in a Christian world that includes citizenship, faith, love, individuality, and meaning. In this way the growing datedness of a film set in a town that was marginal enough for 1979 works to isolate and frame the core existential reality of what it means to be human and thus to increase that feeling of estrangement from the humanity around us when the world, reduced to the borders of a small Maine town, succuumbs to this spiritual “plague.”

While many critics also take aim at the length of the vampire epic, I would suggest that the film is scaled appropriately to the purpose of depicting the town-wide spread of a disease for which the mode of transmission is our closest relationships. And while the medium that is the novel certainly had its advantages over the film adaptation in conveying the scope of this outbreak, I found many departures from the novel critical to the impact of the story (e.g., the modeling of Barlow after Nosferatu rather than George Hamilton and placing the climax of the story in the root cellar of the Marsden House rather than in Eva Miller’s Boarding House).

Hello, good evening and welcome Ben! Firstly, I wish to thank you for reading and, secondly, for such an extensive and intelligent reply! Well, let’s see if I can address each point:

1. David Soul certainly looks the part of Ben Mears, yes, but I’ve definitely witnessed better performances from him before – Ghost Story: Phantom Of Herald Square – and since – Poirot: Death On The Nile (2004). I’ve seen Mr. Mason giving much better performances in much better films around that time, namely Heaven Can Wait (1978), The Boys From Brazil (1978), Murder By Decree (1979), Yellowbeard (1983), and Doctor Fischer Of Geneva (1985). The supporting cast, on the whole, do a fine job – Lance Kerwin, Kenneth McMillan, Elisha Cook, Geoffrey Lewis, George Dzundza, even Fred Willard.

2. I agree that the restraints of television (and lack of budget) forces filmmakers to ‘think on their feet’ and to be creative and imaginative but, at the same time, if the film in question is based on a novel, try not to wander far from the original source (The Keep (1983) is a terrific film, but has very little to do with the excellent F. Paul Wilson novel – now that’s one eighties film that deserves to be remade). Speaking of which, where were the ever-present rats that plagued the novels of both Salem’s Lot and The Keep? They had zillions of rats in Noferatu The Vampyre (1979).

3. In the film Barlow is depicted as a hissing rat-like creature rather than the eloquent villain of the novel, supposedly because producer Richard Kobritz felt a romantic Dracula-type wouldn’t be scary enough. It smacks of laziness on the part of the filmmakers. Look to Anthony Hopkins in Silence Of The Lambs (1991) or even Chris Sarandon in Fright Night (1985) to see how Barlow could have been portrayed. Actor Reggie Nalder had to wear extremely painful contact lenses and makeup as Barlow, and was really pissed off when he found out most of his scenes (and many others) were cut from the final release.

4. Despite the restraints of television, I did mention the taboos that are mildly contravened by Salem’s Lot, and congratulated director Tobe Hooper for his direction of certain scenes, like the cuckolded man who takes revenge. It makes the vampire sequences look a bit hollow in comparison. Salem’s Lot is good Tobe Hooper, but poor Stephen King.

5. In my humble opinion, Salem’s Lot could have been a lot better. I feel neither film version captures the all-embracing quality of an excellent vampire story. Stephen King himself regards the film with relief rather than any form of pride: “At the time of this writing, three of my novels have been released as films: Carrie (1976), Salem’s Lot (1979) and The Shining (1980) and in all three cases I feel that I have been fairly treated – and yet the clearest emotion in my mind is not pleasure but a mental sigh of relief. When dealing with the American cinema, you feel like you won if you just break even. Other one-shot television movies and specials run from the merely forgettable to some really hideous pieces of work. The risk rate is so high that when my own novel Salem’s Lot was adapted for television after Warners had tried fruitlessly to get it off the ground as a theatrical film for three years, my feeling at its generally favourable reception was mostly relief. For a while it seemed that NBC might turn it into a weekly series and, when that rather numbing prospect passed by the boards, I felt relief again.” Stephen King, Dance Macabre, 1981.

DATED BUT SCARY THE BOOK IS A MUST READ ITS STEPHEN KINGS BEST BOOK IMHO