Horror cinema is almost as old as cinema itself, for the very good reason that fantasy is implicit in the very nature of film. Action can be slowed down or speeded up, people can be made to appear or disappear, scale can be altered so that people can become giants or mannequins, double-exposure allows one actor to play two roles simultaneously. The possibilities are endless and they were realised very early – not long after the first commercial showing of motion pictures in 1894. It was no coincidence that professional stage magicians were among the earliest filmmakers.

Horror cinema is almost as old as cinema itself, for the very good reason that fantasy is implicit in the very nature of film. Action can be slowed down or speeded up, people can be made to appear or disappear, scale can be altered so that people can become giants or mannequins, double-exposure allows one actor to play two roles simultaneously. The possibilities are endless and they were realised very early – not long after the first commercial showing of motion pictures in 1894. It was no coincidence that professional stage magicians were among the earliest filmmakers.

Film snobs often talk as if special effects were somehow vulgar – at best, the icing on an otherwise realistic cake. It probably makes more sense to regard special effects as completely fundamental to film, the cake itself. After all, the language and grammar of film is nearly all special effects, but most of the tricks are now so familiar that we pay them no more attention than to nouns, verbs and adjectives in a spoken sentence. Montage, cross-cutting, close-ups, zooms, panning and tracking and all the rest of the filmmakers vocabulary were all, in their day, special effects. Now we take them for granted, but in the earliest days of film-making they did not exist: The camera was plopped down in the visual equivalent of the front row of the stalls, and there it stayed. This did not last for long.

Film snobs often talk as if special effects were somehow vulgar – at best, the icing on an otherwise realistic cake. It probably makes more sense to regard special effects as completely fundamental to film, the cake itself. After all, the language and grammar of film is nearly all special effects, but most of the tricks are now so familiar that we pay them no more attention than to nouns, verbs and adjectives in a spoken sentence. Montage, cross-cutting, close-ups, zooms, panning and tracking and all the rest of the filmmakers vocabulary were all, in their day, special effects. Now we take them for granted, but in the earliest days of film-making they did not exist: The camera was plopped down in the visual equivalent of the front row of the stalls, and there it stayed. This did not last for long.

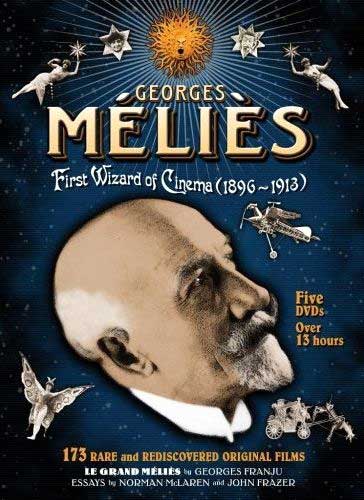

The Frenchman Georges Méliès, a professional illusionist, realised very early (his first films were made in 1896) that the camera could succinctly create illusions that could be made cheaply available to large numbers of ordinary people. Méliès was the son of wealthy parents who indulged him in his desire to be a magician by buying him a theatre, the Theatre Robert-Houdin, where he produced a series of very popular conjuring shows. In 1895 he witnessed the Lumière brothers demonstration of moving pictures and was immediately impressed. First he tried, unsuccessfully, to buy their equipment, then in 1896 he managed to obtain a projector from the English film pioneer Robert Paul who had developed, independently, his own motion picture equipment at the same time as the Lumiere brothers. Méliès converted the projector into a camera, and was soon making his own films.

The Frenchman Georges Méliès, a professional illusionist, realised very early (his first films were made in 1896) that the camera could succinctly create illusions that could be made cheaply available to large numbers of ordinary people. Méliès was the son of wealthy parents who indulged him in his desire to be a magician by buying him a theatre, the Theatre Robert-Houdin, where he produced a series of very popular conjuring shows. In 1895 he witnessed the Lumière brothers demonstration of moving pictures and was immediately impressed. First he tried, unsuccessfully, to buy their equipment, then in 1896 he managed to obtain a projector from the English film pioneer Robert Paul who had developed, independently, his own motion picture equipment at the same time as the Lumiere brothers. Méliès converted the projector into a camera, and was soon making his own films.

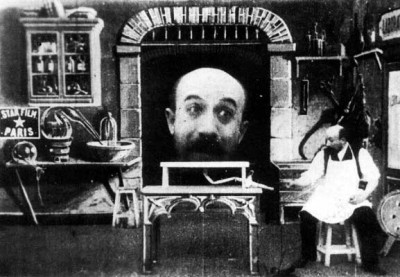

He quickly found that he could go much further than was possible on the stage and he was one of the earliest pioneers of double-exposure, slow and fast motion, even stop-motion, where the film is exposed one frame at a time which allows amazing transformations to take place. Many of his films are now lost, but it’s still possible to see the first science fiction film ever made – A Trip To The Moon (1902). To a modern viewer this short film (it was unusually long for the time at around fifteen minutes) will of course appear contrived, theatrical and far too whimsical. Méliès was not interested in convincing us that what we saw was really happening – he was recreating the splendid nonsense of the pantomime. But it is not too difficult a feat to project our minds back a century or so, and to recapture the extraordinary thrill the film-going public of the time must have felt at the rocket trip through space (a subjective shot, with the face of the Moon racing towards the viewer), the lobster-clawed Selenites (there were chorus girls on the Moon as well), and even the art-nouveau splendours of the Moon Palace. All combine in a surreal potpourri which showed clearly that magic had indeed entered the cinema. As it turned out, magic was never to leave it.

He quickly found that he could go much further than was possible on the stage and he was one of the earliest pioneers of double-exposure, slow and fast motion, even stop-motion, where the film is exposed one frame at a time which allows amazing transformations to take place. Many of his films are now lost, but it’s still possible to see the first science fiction film ever made – A Trip To The Moon (1902). To a modern viewer this short film (it was unusually long for the time at around fifteen minutes) will of course appear contrived, theatrical and far too whimsical. Méliès was not interested in convincing us that what we saw was really happening – he was recreating the splendid nonsense of the pantomime. But it is not too difficult a feat to project our minds back a century or so, and to recapture the extraordinary thrill the film-going public of the time must have felt at the rocket trip through space (a subjective shot, with the face of the Moon racing towards the viewer), the lobster-clawed Selenites (there were chorus girls on the Moon as well), and even the art-nouveau splendours of the Moon Palace. All combine in a surreal potpourri which showed clearly that magic had indeed entered the cinema. As it turned out, magic was never to leave it.

An Impossible Voyage (1904) was the second of Méliès’ science fiction films – it was about a train trip to the Sun. Even more absurdly theatrical than A Trip To The Moon, it remains an awe-inspiring compendium of special effects which, in some cases, have remained almost unchanged to the present day, the combination of live action and painted backdrops, multiple exposures, split-screens, animation, spectacular disasters using models to stand for reality (the train falls into the sea), and stop-motion transformations. In 1907 he applied the same treatment to Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1907), though it’s doubtful whether the illustrious French author would have approved of the half-naked sea nymphs who Melies underwater explorer encounters.

An Impossible Voyage (1904) was the second of Méliès’ science fiction films – it was about a train trip to the Sun. Even more absurdly theatrical than A Trip To The Moon, it remains an awe-inspiring compendium of special effects which, in some cases, have remained almost unchanged to the present day, the combination of live action and painted backdrops, multiple exposures, split-screens, animation, spectacular disasters using models to stand for reality (the train falls into the sea), and stop-motion transformations. In 1907 he applied the same treatment to Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1907), though it’s doubtful whether the illustrious French author would have approved of the half-naked sea nymphs who Melies underwater explorer encounters.

Méliès failed to keep abreast of popular taste for very long and sadly, by 1908, he was being criticised as childish. In 1913 his company went bankrupt and anyway, by then, Europe was on the brink of war. World War One did not, however, prevent the making of films, and it was in one of the major combatant countries, Germany, that the next advances in horror cinema were made. But that’s another story for another time. I’ll now politely request your company next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier again with another feather plucked from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News. Toodles!

Méliès failed to keep abreast of popular taste for very long and sadly, by 1908, he was being criticised as childish. In 1913 his company went bankrupt and anyway, by then, Europe was on the brink of war. World War One did not, however, prevent the making of films, and it was in one of the major combatant countries, Germany, that the next advances in horror cinema were made. But that’s another story for another time. I’ll now politely request your company next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier again with another feather plucked from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews