HorrorNews Interview: Paul Duncan – Horror Cinema

Mike Joy: Its hard to believe that horror cinema has only been around for over 100 years. This book gives the reader an entertaining glimpse through the history of horror on film, from the Edison Studios Frankenstein short film in 1910 to this modern era of horror here in 2010.How long did it take to compile all the knowledge that is trapped in this book?

Paul Duncan: It takes a lifetime for us to gather all our experiences and responses to horror. Luckily on this book we had several lifetimes, those of authors Jonathan Penner and Steven Jay Schneider, and myself.

In practical terms, Steven came on board in 2004, and together we agreed a list of categories, then a list of 200 films (20 for each category) for me to photo research. These 200 films were considered the most representative examples of each category.

We then worked in parallel over the next couple of years: I researched photo libraries in Europe and America, whilst Steven researched the films. However, it was a fluid process. Since Taschen books are primarily visual books, I felt free to explore images of films that were outside our ‘essential 200’ to find killer photos that blew me away, or simply made me laugh. This happened time and again when I was looking through David Del Valle’s photo collection, which is full of marvels. For example, David had this fantastic pic of Tippi Hedren filming The Birds (1963), with Tippi in the phone box and half a dozen wranglers throwing birds at her. Another one that made me laugh out loud was a still from The Devil Bat (1940), which has the eponymous devil bat in the foreground left, Suzanne Kaaren cowering, and a maniacal Bela Lugosi peering at her through the window.

Bela’s face is priceless. David also had a fun pic of Beverly Garland kissing an alligator on the set of The Alligator People (1959).At The Kobal Collection, I looked through every single film in their filing cabinets – which, I must say, is a rare honor – and found some gems, including a still of a female werewolf from ‘La lupa mannara’ (1976), which the Italian producers claimed was based on a true story.I also researched images at the British Film Institute in London, who have a magnificent collection of Hammer images, and at defd in Hamburg. The icing on the cake was Joe Dante, who generously supplied images from his films.

Once the photo research was complete, I organized the layouts and started to have fun. Some spreads illustrated a single film, some illustrated a theme, and some are just fun. For example, as I grouped photos for the Demons and Tricksters chapter, I noticed that several featured two characters embracing, about to kiss. So I grouped the images from Hellbound: Hellraise II (1988), Candyman (1992) and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) on a single page, which seemed to work. This idea of the evil transmitting itself through carnal pleasures therefore corrupting the innocent is not new and is a visual motif that runs through the book, from Nosferatu (1922) to Dracula (1931) to Goke: Body Snatcher From Hell (1968) to The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971) to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992).

With the layout complete, I handed it over to Steven, who then tailored his outline text to the selected films and images. However, due to his heavy workload as a film producer, he called in friend Jonathan Penner to take over. Et viola! Book done.

Mike Joy: You have broken down the horror genre in the following categories, 1 Slashers & Serial Killers, 2 Cannibals, Freaks, & Hillbillies, 3 Revenge of Nature & Environmental Horror, 4 Sci-Fi Horror, 5 The Living Dead, 6 Ghosts & Haunted Houses, 7 Possession, Demons, & Tricksters, 8 Voodoo, Cults, & Satanists, 9 Vampires & Werewolves, 10 The Monstrous Feminine. Why did you choose this format instead of horror by decade?

Paul Duncan: I had already commissioned two other genre books in the series, on Film Noir and Erotic Cinema, and found that breaking down the genre by subject was just more interesting. It allowed the authors to follow the threads of the subject as it evolved, morphed and jumped around over time. It is also more interesting visually to follow something like, say Serial Killer movies. Of course you start with Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927) and Psycho (1960).

Then you see that the image of Norman Bates approaching the house is very similar to John Carpenter’s framing of Michael Myers as he approaches the house in Halloween (1978). Then slasher movies like Friday the 13th (1980) hark back to the visceral imagery of Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs (1964). The use of mirrors and reflections is endemic in these kind of films, pointing out the duality of the way the characters are presented (innocent on the outside, inhuman on the inside), so I had a spread of Peter Lorre pulling faces in the mirror in Fritz Lang’s M (1931), reflections of the killer in Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) and Terry O’Quinn writing ‘Who Am I Here?’ on a misted mirror in The Stepfather (1987).

Luis Bunuel talked about an unconscious visual film language transmitted through the decades from filmmaker to filmmaker, and part of my method of making this and other film books is to allow that unconscious language to become conscious in the minds of the readers. For example, I included an image from The Silence of the Lambs ( 1991) of Jodie Foster in the dark with a hand hovering menacingly behind her. This is a direct visual quote from Paul Leni’s The Cat and the Canary (1927) and James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932). Putting threads of these visual motifs throughout the book is a way for me to give the book, and the genre, a visual coherence.

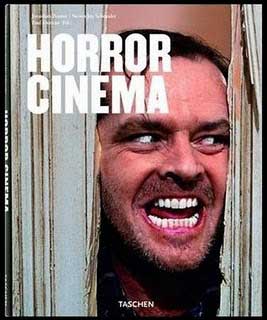

Mike Joy: There are hundreds, dare I say thousands, of classic horror scenes that you could have picked from, but its the terrifying Jack Torrance ( Jack Nicolson ) peaking through the broken door from The Shining that made the final cut/chop for the front cover. What made you decide on Jack?

Paul Duncan: Putting Jack on the cover was publisher Benedikt Taschen’s idea. The image is iconic, instantly recognizable, and it helped a lot that we had access to Stanley Kubrick’s original film negative to get the best ever scan of the moment when Jack says, “Heeeere’s Johnny!”

There’s were other images that I suggested for the cover, some of which are in the book, like the serenely gothic Gary Oldman lording it over his three brides in a still from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but I think that Benedikt got it right.

Mike Joy: This book contains the whos who of horror and it features not only the classics, but also some lesser known movies like Prophecy. This is a movie that I really appreciate being mentioned / and pictured , because its one of those forgotten and hard to find titles that brings me back to discovering horror as an adolescent. What was the criteria that you used in picking the horror movies featured in the book?

Paul Duncan: Initially, we selected a film because it contained an idea that we wanted to illustrate the theme, as well as the film being seminal and/or well-known. However, as I researched the images, I found that there are actually very few good quality images that encapsulate the idea of the movie. This is when I had to think more laterally and expand the range of the films.

Looking through the book now, I can see that I have included many of my favorite horror movies. As a child, I remember cowering behind the sofa when King Kong (1933) was on TV. That was part of a TV festival of SF-Horror films that had a profound effect on mini-me, which included Them! (1954), Cat People (1942), and Village of the Damned (1960). A little older, I saw The Wicker Man (1973) before it became such a cult and that absolutely scared the sh*t out of me (can I say that?), as did the films of Dario Argento (Deep Red (1975), Suspiria (1977)) and Brian De Palma (Carrie (1976)). Don’t Look Now (1973), Alien (1979), Dawn of the Dead (1978), The Vanishing (1988) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) are all high on my list of favorites… so it’s not as if the films in the book are contentious, or even unusual, but I would venture to say that the selection of images are unusual and of high quality.

Mike Joy: Now, related to the last question, when it came down to editing the book, were there a lot of movies that were left out, either not mentioned or not pictured?

Paul Duncan: A lot of film images were not included because of space restrictions. With all the photo research I did, I could have easily compiled a collection of eight 600-page books without a drop in standards. But the nature of editing means that, as William Faulkner put it so elegantly, you have to kill your darlings.

Conversely, I also found that there are often films for which no decent imagery survive, or for which there are many images but not the specific moment or shot you are looking for. This is quite common in the film industry because as the movies are being shot nobody knows for sure which scenes or images will have the most impact. What’s great about looking through the photos afterwards is that they become a sort of visual history of the film and we act as archeologists trying to decipher the images decades later.

Mike Joy: Did you consider adding any additional sub-genres as categories? An example might be Monster Machines with movies like The Car, Christine, Duel, and Maximum Overdrive.

Paul Duncan: We tried to make the categories as wide-ranging as possible, so that we could put every horror film into at least one of them. For your example, all of them would fit into chapter 7: Possession, Demons & Evil Tricksters.

Mike Joy: On nearly every page, there are timeless quotes from some horror giants. You have quotes from Stephen King, Wes Craven, Roger Corman, John Carpenter, and Vincent Price just to name a few. There are also some excellent movie quotes. Do you have a favorite quote that was printed in the book?

Paul Duncan: I think the Friedrich Nietzsche quote that opens the book says it all: “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

What I love about this quote is the idea that the ‘monsters’ or the ‘abyss’ (i.e. the unknown) might infect us and take us over. In horror cinema this is often shown physically as a virus that turns us into zombies, or vampires or werewolves, but it is also shown psychologically as our minds being taken over by an idea (a cult), or a compulsion (serial killers), or simply breaking under the strain.

Ultimately, horror is about us losing control, and all these movies play on that fear so that we can express it in some way.

Mike Joy: Which decade produced the best horror movies?

Paul Duncan: When Steven first sent me a list of 200 films, I listed them by decade and found that over 50% of them were from the 1970s and 1980s. We restructured the list to include more from other decades, but the 70s/80s were an incredibly fertile time because the rise of video technology allowed viewers to access many more films, and a new generation of film-school graduates entered the industry wanting to make money (horror is probably the safest investment for a producer) as well as pay homage to the films of their youth. So all hail the rise of the slasher movie!

However, beauty lies in the eye of the beholder, and I think the best period all comes down to personal preference. Some prefer the Universal horror films of the 1930s, some the cold war movies of the 1950s, or the Hammer Films of the 1960s, or the recent spate of J-Horror and K-Horror.

Personally, I think there is room for all views on the subject, and we tried to encompass as many of these as we could in the limited space available.

Mike Joy: Well, weve learned a lot about the history of Horror Cinema. What do you foresee for the future of Horror Cinema?

Paul Duncan: In recent years there has been a rise in what has been termed ‘torture p*rn’, where the blood flows excessively, cruelly and without humanity. I think the inhuman aspect of this disturbs me most, since I feel we always need a human element in a film for it to resonate with an audience. However, some of the films in this subgenre are excellent – I loved Alexandre Aja’s Haute Tension (2003), and thought Wolf Creek (2005) very unsettling because it smacked of reality. But the Hostel and Saw series just leave me cold. Recently I had a Kiyoshi Kurosawa mini-filmfest at home and thought Cure (1997) and Kairo (2001) two of the best horror films I’ve seen in a long time. I loved Neil Marshall’s The Descent (2005), and Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead (2004). These are all diverse films from around the world. The future of horror cinema is bright but, as ever, those bright spots will reveal themselves slowly and unexpectedly, just when you least expect them.

Paul Duncan has edited 50 film books for TASCHEN, including the award-winning The Ingmar Bergman Archives, and authored Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick in the Film Series. He recently edited The Godfather Family Album, Taxi Driver, Art Cinema and The Art of Bollywood. Forthcoming is a gigantic book on James Bond for the 50th Anniversary in 2012.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews