Scientific knowledge was never one of the requirements needed for a successful Hollywood scriptwriter. At least science fiction authors are usually aware of scientific flaws and try to disguise them with pseudo-science. For instance, they’ve long got around Einstein’s law regarding the impossibility of faster-than-light travel by taking a short-cut through ‘hyper-space’. My old friend H.G. Wells was well aware of the fact that a totally transparent man would also be totally blind, since the light would pass straight through the retinas of the eyes without exciting the optic nerves, but instead he diverted attention to all the other problems of being invisible (such as half-digested meals still being visible within the body for several hours) in his marvelous novel The Invisible Man.

Scientific knowledge was never one of the requirements needed for a successful Hollywood scriptwriter. At least science fiction authors are usually aware of scientific flaws and try to disguise them with pseudo-science. For instance, they’ve long got around Einstein’s law regarding the impossibility of faster-than-light travel by taking a short-cut through ‘hyper-space’. My old friend H.G. Wells was well aware of the fact that a totally transparent man would also be totally blind, since the light would pass straight through the retinas of the eyes without exciting the optic nerves, but instead he diverted attention to all the other problems of being invisible (such as half-digested meals still being visible within the body for several hours) in his marvelous novel The Invisible Man.

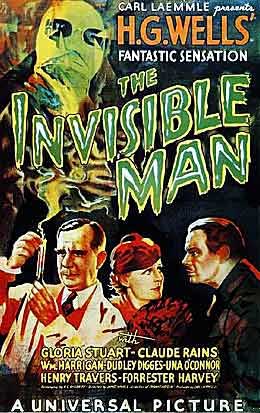

Many of the more interesting elements in H.G.’s novel were discarded when it came to being adapted for the screen but the film The Invisible Man (1931) still remains a very impressive and entertaining piece of work, though Wells himself didn’t share that opinion. He was, however, fortunate in having a very talented team of people involved in the production of the film.

Many of the more interesting elements in H.G.’s novel were discarded when it came to being adapted for the screen but the film The Invisible Man (1931) still remains a very impressive and entertaining piece of work, though Wells himself didn’t share that opinion. He was, however, fortunate in having a very talented team of people involved in the production of the film.

The director was James Whale, who had just directed Frankenstein (1931), the script was written by R.C. Sherriff, Claude Rains played the invisible man, and top effects man John P. Fulton handled the special effects. Whale and Sherriff may have diluted some of the horror in their adaptation, but they did concentrate on the strong streak of black humour that runs through the book and the result was a very amusing picture in which the comedy was far more than a shade sick.

There is also a great deal of gleeful anarchy in it, and I feel that Whale and Sherriff had more sympathy with the invisible man (who has been turned into a raving megalomaniac due to a side-effect of the invisibility drug) than with his victims. They certainly seemed to derive pleasure from making the British policemen in the film look ridiculous.

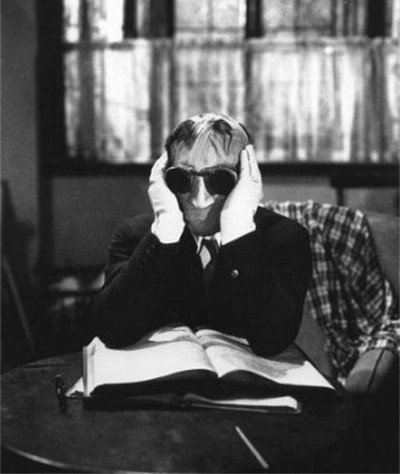

As the mad scientist Griffin, Claude Rains gives a memorable performance despite being heard but not seen for most of the film. In the early scenes his face is covered in bandages and it is not until he dies in the hospital that the audience receives a glimpse of him. For the rest of the film he is entirely invisible or represented by various articles of apparently empty clothing – shirt, trousers, dressing gown and so on. John P. Fulton, in charge of the effects department at Universal for many years, made use of an improved traveling matte system based on one originally devised by effects innovator Frank Williams, whose assistant he had once been.

As the mad scientist Griffin, Claude Rains gives a memorable performance despite being heard but not seen for most of the film. In the early scenes his face is covered in bandages and it is not until he dies in the hospital that the audience receives a glimpse of him. For the rest of the film he is entirely invisible or represented by various articles of apparently empty clothing – shirt, trousers, dressing gown and so on. John P. Fulton, in charge of the effects department at Universal for many years, made use of an improved traveling matte system based on one originally devised by effects innovator Frank Williams, whose assistant he had once been.

Screenwriter-novelist Curt Siodmak was at his busiest in Hollywood during the forties but his screenplays tended to have a foot in both the pseudo-science and the horror camps. Strangely enough he had nothing to do with the screenplay of his most famous novel, Donovan’s Brain. Under the title The Lady And The Monster (1944) it was directed by George Sherman and scripted by Diane Lussier and Frederick Kohner. Incredibly, neither Boris Karloff nor Bela Lugosi appears in it. Instead the cast includes Vera Ralston, Richard Arlen, and Erich von Stroheim.

Screenwriter-novelist Curt Siodmak was at his busiest in Hollywood during the forties but his screenplays tended to have a foot in both the pseudo-science and the horror camps. Strangely enough he had nothing to do with the screenplay of his most famous novel, Donovan’s Brain. Under the title The Lady And The Monster (1944) it was directed by George Sherman and scripted by Diane Lussier and Frederick Kohner. Incredibly, neither Boris Karloff nor Bela Lugosi appears in it. Instead the cast includes Vera Ralston, Richard Arlen, and Erich von Stroheim.

The first of at least three film versions of the novel, the basic story remains the same in all of them: Financial wizard W.H. Donovan is killed when his plane crashes in the desert but a scientist, whose laboratory is near the crash site, removes Donovan’s undamaged brain from his body and keeps it alive in a glass tank.

Donovan’s personality, however, is so dominant that the brain eventually takes over the minds of those people around it, forcing them to carry out Donovan’s evil plans and, of course, all ends in disaster. However, instead of investigating the reactions of the disassociated brain to its total sensory deprivation, Curt turns his story into yet another description of innocence being overcome by an evil supernatural force. What the original idea called for was a science fiction writer rather than one who was really (despite his customary trappings of pseudo-science) an exponent of Gothic melodrama. But as usual, I digress.

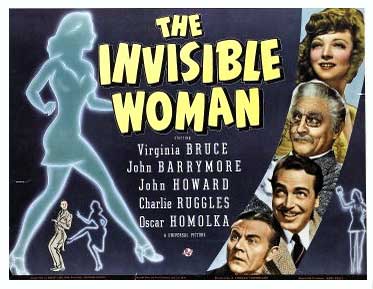

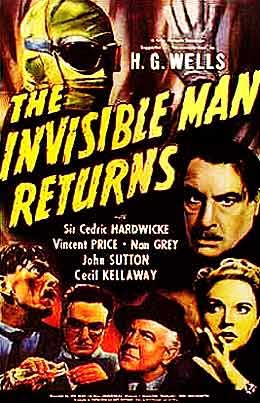

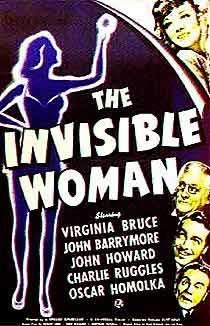

Curt was on safer ground with his story for The Invisible Woman (1940), which he wrote in collaboration with Joe May. It was his second excursion into invisibility – Curt and Joe had written the story for The Invisible Man Returns (1939) starring Vincent Price, which Joe had directed. Joe, like Curt, was a self-exiled German and had been prominent in the German film industry from its earliest days directing serials and thrillers – his real name was Joseph Mandel. The Invisible Woman, directed by Edward Sutherland, is a light and moderately amusing film whose only real claim to fame was that it featured one of the first full-frontal female nudes in commercial cinema. True, it was an invisible nude, but back in 1940 it was the thought that counted to the adolescent males in the audience.

Curt was on safer ground with his story for The Invisible Woman (1940), which he wrote in collaboration with Joe May. It was his second excursion into invisibility – Curt and Joe had written the story for The Invisible Man Returns (1939) starring Vincent Price, which Joe had directed. Joe, like Curt, was a self-exiled German and had been prominent in the German film industry from its earliest days directing serials and thrillers – his real name was Joseph Mandel. The Invisible Woman, directed by Edward Sutherland, is a light and moderately amusing film whose only real claim to fame was that it featured one of the first full-frontal female nudes in commercial cinema. True, it was an invisible nude, but back in 1940 it was the thought that counted to the adolescent males in the audience.

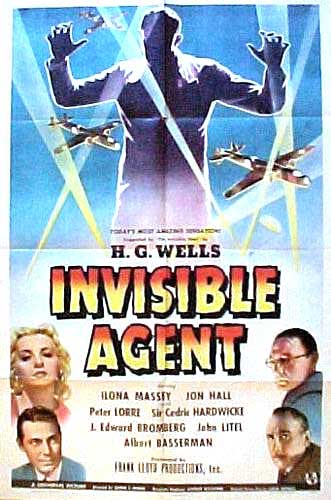

In 1942 it was the female audiences turn to be titillated by the sight of the invisible Jon Hall who appeared, as it were, in The Invisible Agent (1942). Curt’s screenplay had the son of the original invisible man (now calling himself Frank Raymond) volunteering to the US authorities shortly after Pearl Harbour, to use what little remained of the invisibility serum on a secret mission in Germany.

In 1942 it was the female audiences turn to be titillated by the sight of the invisible Jon Hall who appeared, as it were, in The Invisible Agent (1942). Curt’s screenplay had the son of the original invisible man (now calling himself Frank Raymond) volunteering to the US authorities shortly after Pearl Harbour, to use what little remained of the invisibility serum on a secret mission in Germany.

He is then parachuted, invisible, from a plane over Berlin and once on the ground he makes successful contact with a female agent (Ilona Massey) who, understandably, takes a little time to adjust to his unique ‘appearance’. Soon afterward she receives a visit from the head of the ‘secret Nazi police’ who discloses that Hitler plans an immediate attack on the USA. With the girl’s help the invisible man secures a list belonging to a Japanese spy called Ikito (Peter Lorre doing a sort of villainous Mister Moto routine) which contains the names of all the Nazi and Japanese spies in America. Ikito almost succeeds in trapping him with a silk net lined with sharp hooks but, though injured, he escapes.

Then he and the girl commandeer a German bomber and fly back to England, a stunt performed with casual regularity in Hollywood films during the war. Though pure escapism, The Invisible Agent is completely different in tone from the frivolous The Invisible Woman, a sign of how quickly even comic book characters were harnessed to the propaganda machine. It’s a typical Hollywood irony that, in this case, it was a German writer providing the propaganda.

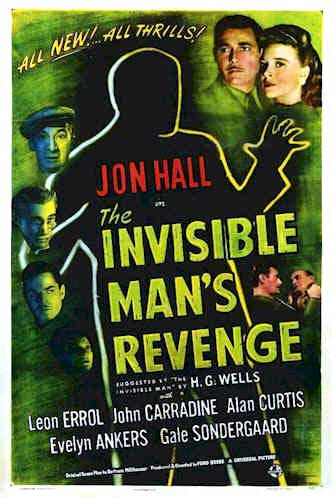

The war was ignored in the next installment of The Invisible Man saga, but the downbeat mood was continued in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), directed by Ford Beebe and written by Bertram Millhauser. Jon Hall once again played the lead character but for the first time since the 1933 version, he was an unsympathetic one, and his end was suitably macabre – killed by an invisible Great Dane.

The war was ignored in the next installment of The Invisible Man saga, but the downbeat mood was continued in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), directed by Ford Beebe and written by Bertram Millhauser. Jon Hall once again played the lead character but for the first time since the 1933 version, he was an unsympathetic one, and his end was suitably macabre – killed by an invisible Great Dane.

And with that The Invisible Man saga came to an end on the cinema screen, though his character did re-emerge on television, first in a British-made adventure series in 1957 and then in an American series in 1975, finally to have the original Wells novel given the respect it deserved in the 1984 BBC six-part television serial.

Anyway, I respectfully request your persistence…I mean, presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic dog from…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews