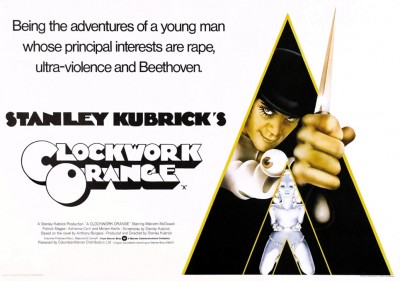

With The Andromeda Strain (1971) director Robert Wise proved that he was still as adept with science fiction themes as he was with the supernatural. A well constructed thriller, it tells of a group of scientists trying to analyse a strange alien spore which comes to earth. Stanley Kubrick, having explored the sterile depths of space in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), returned to a grungy Earth to show what might be happening in the same future year with A Clockwork Orange (1971). Starring Malcolm McDowell as a teenage hoodlum, the film successfully adapts Anthony Burgess‘ chilling political parable into an exciting and controversial movie. Some critics were aghast at the level of visceral violence on show in the feature and many failed to see that the director was using the powerful medium of film to make a valid philosophical point: To take away one’s freedom of choice (even to follow a violent lifestyle) is an even worse crime than the violence itself.

With The Andromeda Strain (1971) director Robert Wise proved that he was still as adept with science fiction themes as he was with the supernatural. A well constructed thriller, it tells of a group of scientists trying to analyse a strange alien spore which comes to earth. Stanley Kubrick, having explored the sterile depths of space in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), returned to a grungy Earth to show what might be happening in the same future year with A Clockwork Orange (1971). Starring Malcolm McDowell as a teenage hoodlum, the film successfully adapts Anthony Burgess‘ chilling political parable into an exciting and controversial movie. Some critics were aghast at the level of visceral violence on show in the feature and many failed to see that the director was using the powerful medium of film to make a valid philosophical point: To take away one’s freedom of choice (even to follow a violent lifestyle) is an even worse crime than the violence itself.

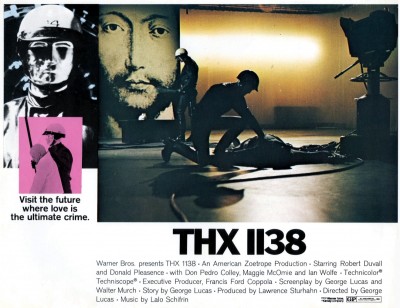

The six years following A Clockwork Orange saw a wide array of science fiction and horror films, many of which lay the groundwork for the features still flooding our screens today. A budding film-school student named George Lucas directed his first feature, the 1984-like THX-1138 (1971), and superstar Clint Eastwood made his directorial debut with Play Misty For Me (1971), a shocker about a knife-weilding stalker. Douglas Trumbull, who had provided many of the eye-catching effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Andromeda Strain, sat in the director’s chair for the first time with Silent Running (1971), a partially successful attempt to blend science fiction hardware with a more humanistic approach to characterisation and plotting – an interesting idea.

The six years following A Clockwork Orange saw a wide array of science fiction and horror films, many of which lay the groundwork for the features still flooding our screens today. A budding film-school student named George Lucas directed his first feature, the 1984-like THX-1138 (1971), and superstar Clint Eastwood made his directorial debut with Play Misty For Me (1971), a shocker about a knife-weilding stalker. Douglas Trumbull, who had provided many of the eye-catching effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Andromeda Strain, sat in the director’s chair for the first time with Silent Running (1971), a partially successful attempt to blend science fiction hardware with a more humanistic approach to characterisation and plotting – an interesting idea.

Also: see

1920s Genre Films

1930s Genre Films

1940s Genre Films

1950s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1980s Genre Films

But it was the Warner Brothers production of The Exorcist (1973) which revitalised the horror genre. Based on William Peter Blatty‘s sensational novel, The Exorcist marked the first time that graphic horror, packaged in a slickly produced and directed movie, was aimed squarely at mainstream movie-goers. The overwhelming box-office success of the feature proved the Warner Brothers marketing department right. Although The Exorcist is actually a repulsive film on several levels, not the least of which is seeing a teenage girl (Linda Blair) turned into a urinating, bile-vomiting, foul-mouthed monster, there’s no denying the impact the feature had on both its audiences and the fantasy genre as a whole, paving the way for subsequent shockers as Carrie (1976), The Omen (1976), The Sentinel (1977) and Alien (1979).

But it was the Warner Brothers production of The Exorcist (1973) which revitalised the horror genre. Based on William Peter Blatty‘s sensational novel, The Exorcist marked the first time that graphic horror, packaged in a slickly produced and directed movie, was aimed squarely at mainstream movie-goers. The overwhelming box-office success of the feature proved the Warner Brothers marketing department right. Although The Exorcist is actually a repulsive film on several levels, not the least of which is seeing a teenage girl (Linda Blair) turned into a urinating, bile-vomiting, foul-mouthed monster, there’s no denying the impact the feature had on both its audiences and the fantasy genre as a whole, paving the way for subsequent shockers as Carrie (1976), The Omen (1976), The Sentinel (1977) and Alien (1979).

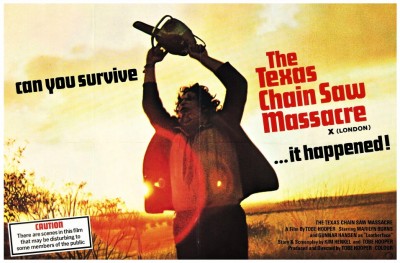

Then came The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), a low budget horror film still lauded today as one of the most terrifying films ever made. Although there is actually little violence on-screen, Tobe Hooper‘s direction is so persuasive that many people who see the film are certain that they have witnessed actual dismemberment by the title’s implement. It is a masterpiece of editing and the use of sound in its creation of a nightmare of extended horror – the film is, in effect, one long climax. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was also to have a profound effect on the horror sub-genre that became to be known as the ‘bodycount’ film, a cycle which still continues to this day.

Then came The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), a low budget horror film still lauded today as one of the most terrifying films ever made. Although there is actually little violence on-screen, Tobe Hooper‘s direction is so persuasive that many people who see the film are certain that they have witnessed actual dismemberment by the title’s implement. It is a masterpiece of editing and the use of sound in its creation of a nightmare of extended horror – the film is, in effect, one long climax. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was also to have a profound effect on the horror sub-genre that became to be known as the ‘bodycount’ film, a cycle which still continues to this day.

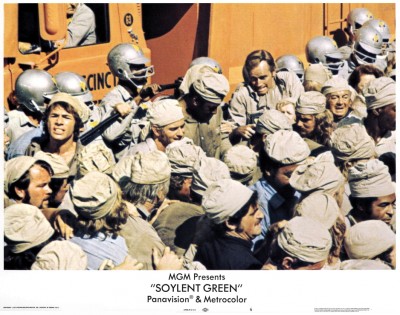

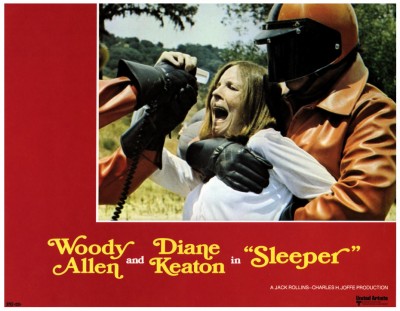

More traditional science fiction fare could also be found in the seventies with such features as Slaughterhouse Five (1972), an above average attempt to bring the generally unfilmable Kurt Vonnegut to the screen. Soylent Green (1973), directed by Richard Fleischer, proved that Charlton Heston was something of a sci-fi ‘everyman’ in a rather plodding adaptation of Harry Harrison‘s novel Make Room! Make Room! and author Michael Crichton made his directorial debut with Westworld (1973), a rather clever parody of Disneyland-style theme parks. Even Woody Allen, former comedy writer and future film auteur, entered the genre with Sleeper (1973) an often hilarious comedy which manages to send up everything from Verne and Wells to Huxley and Orwell.

More traditional science fiction fare could also be found in the seventies with such features as Slaughterhouse Five (1972), an above average attempt to bring the generally unfilmable Kurt Vonnegut to the screen. Soylent Green (1973), directed by Richard Fleischer, proved that Charlton Heston was something of a sci-fi ‘everyman’ in a rather plodding adaptation of Harry Harrison‘s novel Make Room! Make Room! and author Michael Crichton made his directorial debut with Westworld (1973), a rather clever parody of Disneyland-style theme parks. Even Woody Allen, former comedy writer and future film auteur, entered the genre with Sleeper (1973) an often hilarious comedy which manages to send up everything from Verne and Wells to Huxley and Orwell.

Jaws (1975), a briskly directed horror/adventure yarn from a young Steven Spielberg, was the highlight of the year. Within six months of its initial release, Jaws became the top-grossing film of all-time, a feat that caused Hollywood moguls to rethink the profit potential of movies as a whole. Two Jaws sequels followed, Jaws II (1976) and Jaws 3-D (1983), neither of which featured any of the finesse of Spielberg’s original.

Jaws (1975), a briskly directed horror/adventure yarn from a young Steven Spielberg, was the highlight of the year. Within six months of its initial release, Jaws became the top-grossing film of all-time, a feat that caused Hollywood moguls to rethink the profit potential of movies as a whole. Two Jaws sequels followed, Jaws II (1976) and Jaws 3-D (1983), neither of which featured any of the finesse of Spielberg’s original.

Rollerball (1975) appeared soon after to much fanfare from studio publicity hacks. While the rollerball games themselves are brilliantly staged and edited, the surrounding story (based on William Harrison‘s short story The Rollerball Murders) is trite and one-dimensional. Nevertheless, it now looks like a classic when compared to the 2002 remake. Science fiction again received shoddy treatment in Logan’s Run (1976), a cloddishly directed fantasy starring Michael York and Jenny Agutter. Despite a big budget and its excellent source material, an excitingly written novel by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson, the failure of Logan’s Run almost single-handedly put an end to the science fiction cycle of the seventies.

Rollerball (1975) appeared soon after to much fanfare from studio publicity hacks. While the rollerball games themselves are brilliantly staged and edited, the surrounding story (based on William Harrison‘s short story The Rollerball Murders) is trite and one-dimensional. Nevertheless, it now looks like a classic when compared to the 2002 remake. Science fiction again received shoddy treatment in Logan’s Run (1976), a cloddishly directed fantasy starring Michael York and Jenny Agutter. Despite a big budget and its excellent source material, an excitingly written novel by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson, the failure of Logan’s Run almost single-handedly put an end to the science fiction cycle of the seventies.

George Lucas had been hawking his script The Star Wars around various Hollywood studios since 1975 and, despite his success with his American Graffiti (1973) for Universal, he found no takers – the box-office failure of Rollerball and Logan’s Run had seen to that. In 1976 he approached Alan Ladd Junior, then production chief at 20th Century Fox. While not overly impressed with the script, a rehash of Flash Gordon-style space adventures, he was impressed by the director’s enthusiasm for his project and belief in its potential success. Ladd green-lighted the film, now known as Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977), went into production at EMI-Elstree studios in England. About the same time Steven Spielberg, considered Hollywood’s Golden Boy since Jaws, was putting his science fiction film, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) into production in a disused dirigible hangar in Mobile, Alabama.

George Lucas had been hawking his script The Star Wars around various Hollywood studios since 1975 and, despite his success with his American Graffiti (1973) for Universal, he found no takers – the box-office failure of Rollerball and Logan’s Run had seen to that. In 1976 he approached Alan Ladd Junior, then production chief at 20th Century Fox. While not overly impressed with the script, a rehash of Flash Gordon-style space adventures, he was impressed by the director’s enthusiasm for his project and belief in its potential success. Ladd green-lighted the film, now known as Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977), went into production at EMI-Elstree studios in England. About the same time Steven Spielberg, considered Hollywood’s Golden Boy since Jaws, was putting his science fiction film, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) into production in a disused dirigible hangar in Mobile, Alabama.

When Star Wars first opened in May 1977, nobody could have conceived of its phenomenal success. Its simple tale of good versus evil set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” captured the public’s imagination in a way never experienced before in the history of cinema. Audiences were not content to see the film once or even twice – people were lining up to watch the adventures of Luke Skywalker over and over again. Along with the film came the merchandising, everything from toys to wallpaper, it was the start of an industry, the most successful of its kind since MIckey Mouse. Other direct results of the success of Star Wars include Superman The Movie (1978), The Black Hole (1979) and Star Trek The Motion Picture (1979). The effect of the Lucas film was also felt in television with such series as Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers In The 25th Century. Furthermore, it’s unlikely Alien (1979) would have found big studio backing had not Star Wars paved the way.

When Star Wars first opened in May 1977, nobody could have conceived of its phenomenal success. Its simple tale of good versus evil set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” captured the public’s imagination in a way never experienced before in the history of cinema. Audiences were not content to see the film once or even twice – people were lining up to watch the adventures of Luke Skywalker over and over again. Along with the film came the merchandising, everything from toys to wallpaper, it was the start of an industry, the most successful of its kind since MIckey Mouse. Other direct results of the success of Star Wars include Superman The Movie (1978), The Black Hole (1979) and Star Trek The Motion Picture (1979). The effect of the Lucas film was also felt in television with such series as Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers In The 25th Century. Furthermore, it’s unlikely Alien (1979) would have found big studio backing had not Star Wars paved the way.

While Close Encounters Of The Third Kind didn’t quite equal the popularity of Star Wars, it did extremely well, further enhancing and consolidating Spielberg’s reputation. While vacationing in Hawaii together just prior to the release of their respective films, Lucas and Spielberg started formulating plans for their first joint venture, a serial-like action extravaganza featuring archeologist adventurer Indiana Jones, a character created by acclaimed writer-director Phillip Kaufman. The resultant movie, Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), again smashed box-office records.

While Close Encounters Of The Third Kind didn’t quite equal the popularity of Star Wars, it did extremely well, further enhancing and consolidating Spielberg’s reputation. While vacationing in Hawaii together just prior to the release of their respective films, Lucas and Spielberg started formulating plans for their first joint venture, a serial-like action extravaganza featuring archeologist adventurer Indiana Jones, a character created by acclaimed writer-director Phillip Kaufman. The resultant movie, Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), again smashed box-office records.

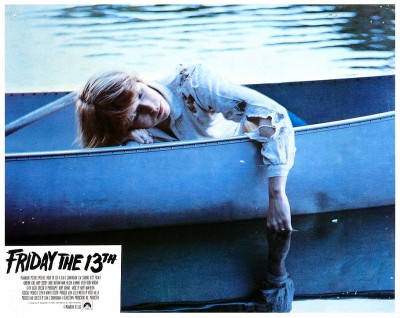

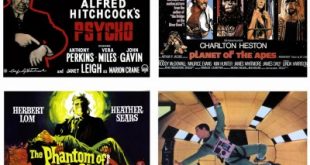

The staggering success of Star Wars and Close Encounters shook Hollywood to its foundations. Suddenly, big budget science fiction and fantasy were acceptable again, and producers started casting around for other suitable science fiction projects. While the queues were still stringing around the block to see Star Wars at the end of 1977, another equally influential film appeared in the shape of John Carpenter‘s Halloween (1978), a low budget exercise in cinematic suspense which owes more than a little to Psycho (1960) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Made at a cost of US$300,000, by the end of the decade had earned in excess of US$40 million. In the wake of Halloween came a slew of imitators, spearheaded by Friday The 13th (1980) from exploitation producer Sean Cunningham. Friday The 13th earned even more than Halloween and spawned at least ten sequels, a remake and countless look-alikes. At this point I’ll thank you for accompanying me on this nostalgic trip through the seventies, and invite you to please join me again next week when I have another opportunity to inflict upon you more tortures of the damned from that dark, bottomless pit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

The staggering success of Star Wars and Close Encounters shook Hollywood to its foundations. Suddenly, big budget science fiction and fantasy were acceptable again, and producers started casting around for other suitable science fiction projects. While the queues were still stringing around the block to see Star Wars at the end of 1977, another equally influential film appeared in the shape of John Carpenter‘s Halloween (1978), a low budget exercise in cinematic suspense which owes more than a little to Psycho (1960) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Made at a cost of US$300,000, by the end of the decade had earned in excess of US$40 million. In the wake of Halloween came a slew of imitators, spearheaded by Friday The 13th (1980) from exploitation producer Sean Cunningham. Friday The 13th earned even more than Halloween and spawned at least ten sequels, a remake and countless look-alikes. At this point I’ll thank you for accompanying me on this nostalgic trip through the seventies, and invite you to please join me again next week when I have another opportunity to inflict upon you more tortures of the damned from that dark, bottomless pit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

No Dario Argento?

Hello, good evening and welcome, Lisa! Oh my goodness, you’re absolutely right! During the seventies and eighties, Grand Guignol had become a specialty of the Italians, directors like Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci, but I believe Argento is the superior craftsman. His Suspiria (1976) is a stylish exercise. Jessica Harper plays the American girl attending a ballet school in a German provincial town. The proprietors of the school are a coven of witches hell-bent, it would seem, on murdering and mutilating their students. The film opens with the heroine, Suzy, leaving a German airport through sliding glass doors. As she goes through, into the wintry night outside, her scarf blows back up around her face as if directed by some invisible strangler, but it is only the wind. Set-piece follows set-piece: Girls are picturesquely murdered in art deco settings; one of them has her head dissected by a pane of coloured glass; maggots rain from the ceiling; the vast halls of the academy glow with coloured light; we hear a stone bird flapping its wings; a blind man has his throat torn out by his own guide-dog; a student falls into a room surrealistically billowing with great coils of bailing wire; a dead girl with pins in her eyes is animated by an invisible witch; Art-Neuvo eyes on a wall hold the secret to hidden passages; whispering can be heard between the rock music tracks. The academy is run by Helena Marcos, who is hundreds of years old and looks it. She is known as the Mother Of Whispers, and is stabbed with a glass dagger – not unlike Argento’s earlier film The Bird With The Crystal Plumage (1970) – plucked from the tail of an ornamental peac**k. The labyrinthine building collapses as Suzy escapes, leaving behind a country of slow-motion Gothic nightmares. The flamboyance of Suspiria was sustained in the sequel Inferno (1980), but that’s a story for another time. Thanks again for reading, and I promise to be more thorough next time. Toodles!