Just as the thirties had been a golden age for Gothic horror films, so the fifties would do the same for science fiction. The power of the atom had undeniably hooked the public on the wonders of science. This, coupled with the development of rocket power and the first major UFO sightings, provided a wealth of exploitable material for the film industry. The first film off the launch pad was to have been Destination Moon (1950), but the word around Hollywood had already spread – space fiction was going to be big – and the independent Lippert production company rushed Rocketship XM (1950) through while the more costly George Pal production was still being shot. Rocketship XM (standing for Expedition Moon) beat Destination Moon into theatres by at least three weeks. Starring Lloyd Bridges, Rocketship XM tells the somewhat pulpy tale of an expedition to the moon that runs off-course and ends up on Mars. There, our intrepid heroes encounter a band of Martian mutants that look like they’ve escaped from a Flash Gordon serial. Oddly enough, Rocketship XM is today far more enjoyable than Destination Moon, a rather slow and ponderous film whose major assets are the superb lunar landscapes created by space artist Chesley Bonestell.

Just as the thirties had been a golden age for Gothic horror films, so the fifties would do the same for science fiction. The power of the atom had undeniably hooked the public on the wonders of science. This, coupled with the development of rocket power and the first major UFO sightings, provided a wealth of exploitable material for the film industry. The first film off the launch pad was to have been Destination Moon (1950), but the word around Hollywood had already spread – space fiction was going to be big – and the independent Lippert production company rushed Rocketship XM (1950) through while the more costly George Pal production was still being shot. Rocketship XM (standing for Expedition Moon) beat Destination Moon into theatres by at least three weeks. Starring Lloyd Bridges, Rocketship XM tells the somewhat pulpy tale of an expedition to the moon that runs off-course and ends up on Mars. There, our intrepid heroes encounter a band of Martian mutants that look like they’ve escaped from a Flash Gordon serial. Oddly enough, Rocketship XM is today far more enjoyable than Destination Moon, a rather slow and ponderous film whose major assets are the superb lunar landscapes created by space artist Chesley Bonestell.

George Pal returned the following year with When Worlds Collide (1951), a film highlighted by some spectacular special effects including the inundation of New York by a tidal wave. 20th Century Fox’s entry for the year was The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) directed by Robert Wise. Based on the Harry Bates short story Farewell To The Master, it revolves around a visitor from another planet whose mission to Earth is to warn the superpowers about their abuse of the atom. To back him up, he has with him a two-and-a-half metre tall robot named Gort. Played by the doorman from Graumann’s Chinese Theatre named Locke Martin, Gort was equipped with a death ray capable of destroying all in its path. Michael Rennie portrays Klaatu, the benevolent alien who finds the human race a generally unfriendly lot, not keen to be told what to do. The Day The Earth Stood Still remains one of the more intelligent science fiction films from the period, greatly enhanced by Wise’s confident direction, moody monochrome photography by Leo Tover and a spine-tingling electronic score by Bernard Herrmann.

George Pal returned the following year with When Worlds Collide (1951), a film highlighted by some spectacular special effects including the inundation of New York by a tidal wave. 20th Century Fox’s entry for the year was The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) directed by Robert Wise. Based on the Harry Bates short story Farewell To The Master, it revolves around a visitor from another planet whose mission to Earth is to warn the superpowers about their abuse of the atom. To back him up, he has with him a two-and-a-half metre tall robot named Gort. Played by the doorman from Graumann’s Chinese Theatre named Locke Martin, Gort was equipped with a death ray capable of destroying all in its path. Michael Rennie portrays Klaatu, the benevolent alien who finds the human race a generally unfriendly lot, not keen to be told what to do. The Day The Earth Stood Still remains one of the more intelligent science fiction films from the period, greatly enhanced by Wise’s confident direction, moody monochrome photography by Leo Tover and a spine-tingling electronic score by Bernard Herrmann.

Also: see

1920s Genre Films

1930s Genre Films

1940s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1970s Genre Films

1980s Genre Films

The other great science fiction thriller that year is The Thing From Another World (1951) produced by Howard Hawks and distributed by RKO. A group of scientists and military personnel are isolated in an arctic research station. One day they discover what appears to be a flying saucer buried in the ice and, nearby, its frozen occupant. The alien is accidentally thawed out and goes on a rampage of destruction throughout the small camp. Although the film is credited as being directed by Christian Nyby (Hawks’ editor), it is generally considered today as a Howard Hawks film. The script by Charles Lederer based on John W. Campbell‘s 1939 novella Who Goes There? fairly bristles with the famed director’s themes – military comradeship, a resourceful heroine and machine-gun fast dialogue. It’s a tightly directed thriller which owes as much to the horror genre as it does to science fiction, and it’s all the more effective for the fact that the alien (played by pre-Gunsmoke James Arness) is glimpsed only fleetingly for most of the picture’s running time.

The other great science fiction thriller that year is The Thing From Another World (1951) produced by Howard Hawks and distributed by RKO. A group of scientists and military personnel are isolated in an arctic research station. One day they discover what appears to be a flying saucer buried in the ice and, nearby, its frozen occupant. The alien is accidentally thawed out and goes on a rampage of destruction throughout the small camp. Although the film is credited as being directed by Christian Nyby (Hawks’ editor), it is generally considered today as a Howard Hawks film. The script by Charles Lederer based on John W. Campbell‘s 1939 novella Who Goes There? fairly bristles with the famed director’s themes – military comradeship, a resourceful heroine and machine-gun fast dialogue. It’s a tightly directed thriller which owes as much to the horror genre as it does to science fiction, and it’s all the more effective for the fact that the alien (played by pre-Gunsmoke James Arness) is glimpsed only fleetingly for most of the picture’s running time.

Just as Universal had led the field in Gothic horror during the thirties, so they would with science fiction throughout the early fifties. When Warner Brothers’ House Of Wax (1953) appeared in 3-D breaking box-office records, the majority of Hollywood studios jumped on the bandwagon (some things never change). Universal was no exception, rushing It Came From Outer Space (1953) into production, about a group of non-aggressive aliens who stop off here to make some running repairs on their spaceship. Under Jack Arnold‘s direction the film makes imaginative use of the 3-D medium and the Southern California desert locations.

Just as Universal had led the field in Gothic horror during the thirties, so they would with science fiction throughout the early fifties. When Warner Brothers’ House Of Wax (1953) appeared in 3-D breaking box-office records, the majority of Hollywood studios jumped on the bandwagon (some things never change). Universal was no exception, rushing It Came From Outer Space (1953) into production, about a group of non-aggressive aliens who stop off here to make some running repairs on their spaceship. Under Jack Arnold‘s direction the film makes imaginative use of the 3-D medium and the Southern California desert locations.

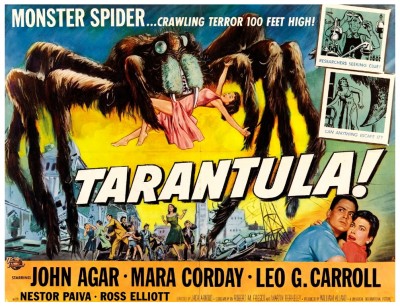

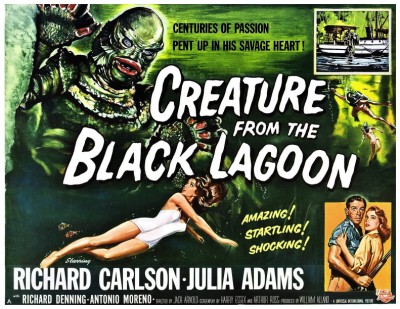

The following year Jack Arnold directed The Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954), a horror thriller about a half-man/half-fish prehistoric monster deep in the Amazon jungles. The 3-D shocker was popular enough to spawn two sequels, Revenge Of The Creature (1955) and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), not to mention the slew of imitations that followed. Arnold returned to the desert locale for one of the best ‘Giant Bug’ movies ever made, Tarantula (1955), about a giant spider terrorising a small town before being dispatched by the air force amid a fireball of napalm. The pilot leading the attack was played by a young Clint Eastwood who, that very same year, also appeared in Revenge Of The Creature and Francis The Talking Mule In The Navy (1955).

The following year Jack Arnold directed The Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954), a horror thriller about a half-man/half-fish prehistoric monster deep in the Amazon jungles. The 3-D shocker was popular enough to spawn two sequels, Revenge Of The Creature (1955) and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), not to mention the slew of imitations that followed. Arnold returned to the desert locale for one of the best ‘Giant Bug’ movies ever made, Tarantula (1955), about a giant spider terrorising a small town before being dispatched by the air force amid a fireball of napalm. The pilot leading the attack was played by a young Clint Eastwood who, that very same year, also appeared in Revenge Of The Creature and Francis The Talking Mule In The Navy (1955).

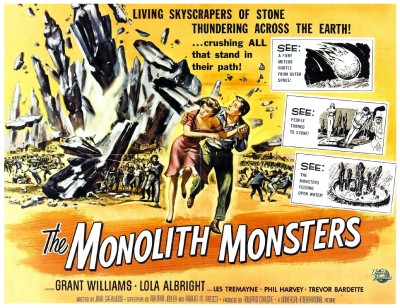

Universal continued throughout the decade, producing generally above-average science fiction movies such as This Island Earth (1955), The Mole People (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957), The Monolith Monsters (1957), The Land Unknown (1957), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), which remains Jack Arnold‘s masterpiece. Based on the Richard Matheson novel, it tells the story of Scott Carey (Grant Williams), a man who is infected by a radioactive mist and finds himself shrinking. A perfect blend of science fiction, adventure and horror, the film benefits greatly from Arnold’s no-nonsense direction, Matheson’s literate screenplay and remarkable special effects by Clifford Stine.

Universal continued throughout the decade, producing generally above-average science fiction movies such as This Island Earth (1955), The Mole People (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957), The Monolith Monsters (1957), The Land Unknown (1957), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), which remains Jack Arnold‘s masterpiece. Based on the Richard Matheson novel, it tells the story of Scott Carey (Grant Williams), a man who is infected by a radioactive mist and finds himself shrinking. A perfect blend of science fiction, adventure and horror, the film benefits greatly from Arnold’s no-nonsense direction, Matheson’s literate screenplay and remarkable special effects by Clifford Stine.

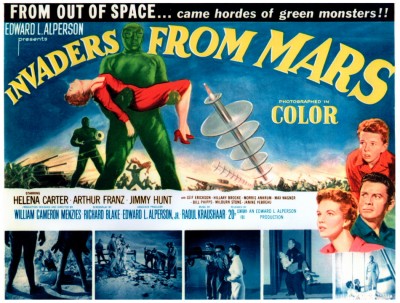

Other studios were exploiting the public’s appetite for science fiction films as well. A spectacular version of H.G. Wells‘ The War Of The Worlds (1953) was produced by George Pal and directed by Byron Haskin. Although little remains of Wells’ original setting, the film is a riveting action masterpiece. William Cameron Menzies, who had directed Things To Come (1936), again returned to science fiction that year with the relatively low-budgeted Invaders From Mars (1953), a multi-layered film steeped in dream-like imagery. Shot entirely from a child’s point of view, a boy witnesses the landing of a UFO. No one will believe him at first, but when various people (including his own parents) are taken over by the Martian monsters and turned into mindless slaves, the US Army steps in to save the day. The twist is, at the end of the film, the entire drama is revealed to be the boy’s nightmare, an ending which was missing from many prints of the film.

Other studios were exploiting the public’s appetite for science fiction films as well. A spectacular version of H.G. Wells‘ The War Of The Worlds (1953) was produced by George Pal and directed by Byron Haskin. Although little remains of Wells’ original setting, the film is a riveting action masterpiece. William Cameron Menzies, who had directed Things To Come (1936), again returned to science fiction that year with the relatively low-budgeted Invaders From Mars (1953), a multi-layered film steeped in dream-like imagery. Shot entirely from a child’s point of view, a boy witnesses the landing of a UFO. No one will believe him at first, but when various people (including his own parents) are taken over by the Martian monsters and turned into mindless slaves, the US Army steps in to save the day. The twist is, at the end of the film, the entire drama is revealed to be the boy’s nightmare, an ending which was missing from many prints of the film.

Even Walt Disney recognised the potential of science fiction and produced Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1954), a multi-million dollar adaptation of Jules Verne‘s classic series of stories. Starring James Mason as Captain Nemo, the film was directed by Richard Fleischer (son of animator Max Fleischer) in fine style, making use of the wealth of technology available at the Disney studios. The special effects are indeed special, in particular the battle with the giant squid during a raging storm at sea, and the production design by Harper Goff lavishly captures the feel of the original stories.

Even Walt Disney recognised the potential of science fiction and produced Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1954), a multi-million dollar adaptation of Jules Verne‘s classic series of stories. Starring James Mason as Captain Nemo, the film was directed by Richard Fleischer (son of animator Max Fleischer) in fine style, making use of the wealth of technology available at the Disney studios. The special effects are indeed special, in particular the battle with the giant squid during a raging storm at sea, and the production design by Harper Goff lavishly captures the feel of the original stories.

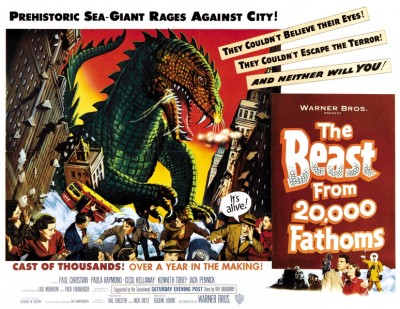

Warner Brothers, too, were keen to cash-in on the boom, and they did so with The Beast From Twenty Thousand Fathoms (1953). About a prehistoric monster defrosted by atomic testing, the film is best remembered today as the first solo effort by stop-motion maestro Ray Harryhausen. Atomic radiation run rampant was the source for Warner Brothers’ other major entry in the science fiction stakes of the fifties, Them! (1954), which detailed in almost documentary fashion the story of a nest of ants enlarged to ginogorous proportions following atomic tests.

Warner Brothers, too, were keen to cash-in on the boom, and they did so with The Beast From Twenty Thousand Fathoms (1953). About a prehistoric monster defrosted by atomic testing, the film is best remembered today as the first solo effort by stop-motion maestro Ray Harryhausen. Atomic radiation run rampant was the source for Warner Brothers’ other major entry in the science fiction stakes of the fifties, Them! (1954), which detailed in almost documentary fashion the story of a nest of ants enlarged to ginogorous proportions following atomic tests.

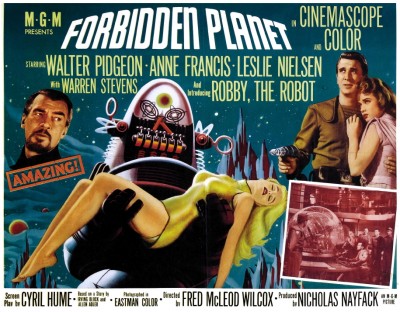

MGM, as ever concerned with quality rather than quantity, produced one of the key fantasies of the fifties, Forbidden Planet (1956). Set on a distant planet in the far future, the story revolves around an expedition searching for a group of space travelers lost years before. They discover all that remains of them on Altair IV: Professor Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) and his beautiful daughter Altaira (Anne Francis). But the mysterious planet holds a grim secret and the remnants of a highly intelligent culture, that of the telepathic Krell. Although the screenplay by Cyril Hume owes much to William Shakespeare‘s The Tempest, the film is tricked out with enough special effects and spectacular scenes to separate it from its origins. Completely shot on the MGM sound stages in front of massive dioramas, Forbidden Planet captures a peculiar mood quite unique for films of the period, a mood rather enhanced by the all-electronic score by Louis & Bebe Barron. Perhaps the single most memorable aspect of the film is Robby The Robot. Capable of producing anything from whiskey to diamonds, the robot is used as a major character in the story.

MGM, as ever concerned with quality rather than quantity, produced one of the key fantasies of the fifties, Forbidden Planet (1956). Set on a distant planet in the far future, the story revolves around an expedition searching for a group of space travelers lost years before. They discover all that remains of them on Altair IV: Professor Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) and his beautiful daughter Altaira (Anne Francis). But the mysterious planet holds a grim secret and the remnants of a highly intelligent culture, that of the telepathic Krell. Although the screenplay by Cyril Hume owes much to William Shakespeare‘s The Tempest, the film is tricked out with enough special effects and spectacular scenes to separate it from its origins. Completely shot on the MGM sound stages in front of massive dioramas, Forbidden Planet captures a peculiar mood quite unique for films of the period, a mood rather enhanced by the all-electronic score by Louis & Bebe Barron. Perhaps the single most memorable aspect of the film is Robby The Robot. Capable of producing anything from whiskey to diamonds, the robot is used as a major character in the story.

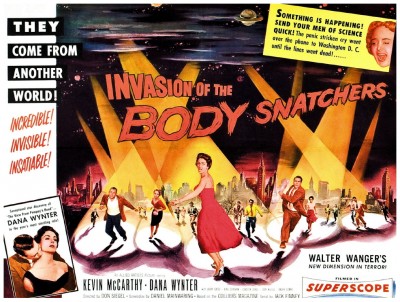

At the heart of many of the ‘alien invasion’ films of the fifties was paranoia, a paranoia fed daily by the television broadcasts of the House of Un-American Activities hearings taking place in Washington. Spearheaded by the megalomaniacal Senator Joseph McCarthy, these hearings ruined the careers of many Hollywood personalities as one-by-one they were hauled before the committee, their lives and films examined in minute detail in an effort to link them with either Communism or Communist-backed organisations. It was a huge Red scare. The best of these metaphorical science fiction thrillers is Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) directed by Don Siegel. In this finely honed chiller, aliens take over the bodies of ordinary people, turning them into unthinking emotionless meat-puppets. With a minimum of special effects, Siegel creates a claustrophobic nightmare of a film in which anyone could be an alien invader. The theme was explored in subsequent features, most notably the minor classic I Married A Monster From Outer Space (1958).

At the heart of many of the ‘alien invasion’ films of the fifties was paranoia, a paranoia fed daily by the television broadcasts of the House of Un-American Activities hearings taking place in Washington. Spearheaded by the megalomaniacal Senator Joseph McCarthy, these hearings ruined the careers of many Hollywood personalities as one-by-one they were hauled before the committee, their lives and films examined in minute detail in an effort to link them with either Communism or Communist-backed organisations. It was a huge Red scare. The best of these metaphorical science fiction thrillers is Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) directed by Don Siegel. In this finely honed chiller, aliens take over the bodies of ordinary people, turning them into unthinking emotionless meat-puppets. With a minimum of special effects, Siegel creates a claustrophobic nightmare of a film in which anyone could be an alien invader. The theme was explored in subsequent features, most notably the minor classic I Married A Monster From Outer Space (1958).

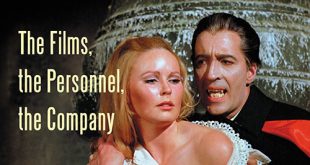

Towards the close of the decade it was apparent that science fiction was running out of steam as the sole basis for fantastic films and producers started to bring back horror. While such late entries as I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957), It The Terror From Beyond Space (1958), The Blob (1958), The Fly (1958) and George Pal‘s The Time Machine (1960) were all based in science fiction, what really attracted the audiences were the horrific aspects of the films. This was further underlined with the success of The Curse Of Frankenstein (1957) produced in England by Hammer. Supposedly a remake of Frankenstein (1931), it starred two actors new to the genre: My old friends Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Where James Whale’s original had been restrained in the showing of the more horrific aspects of the work of Doctor Frankenstein, the Hammer film broke new ground depicting the gory details on-screen.

Towards the close of the decade it was apparent that science fiction was running out of steam as the sole basis for fantastic films and producers started to bring back horror. While such late entries as I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957), It The Terror From Beyond Space (1958), The Blob (1958), The Fly (1958) and George Pal‘s The Time Machine (1960) were all based in science fiction, what really attracted the audiences were the horrific aspects of the films. This was further underlined with the success of The Curse Of Frankenstein (1957) produced in England by Hammer. Supposedly a remake of Frankenstein (1931), it starred two actors new to the genre: My old friends Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Where James Whale’s original had been restrained in the showing of the more horrific aspects of the work of Doctor Frankenstein, the Hammer film broke new ground depicting the gory details on-screen.

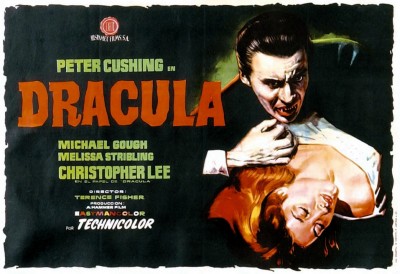

Hammer, Cushing and Lee were hot-to-trot and, to further exploit this success, they regrouped for The Horror Of Dracula (1958), a vibrant retelling of the Bram Stoker classic, decked out with lavish (if low budget) production values, a compelling performance by Lee as the vampire count, and workmanlike uncluttered direction from Terence Fisher. Once more the emphasis was on physical grue and violence though, by today’s standards, this early Hammer horror seems rather tame. But for the time, the formula worked marvelously, and for nearly two decades the studio produced a series of features which, for the most part, proved popular with international audiences. Cushing came back for the first Frankenstein sequel, The Revenge Of Frankenstein (1958), Lee made The Mummy (1959), and the two paired up for a splendid version of The Hound Of The Baskervilles (1959) in which Cushing gives a spirited performance as Sherlock Holmes while Lee portrayed Henry Baskerville.

Hammer, Cushing and Lee were hot-to-trot and, to further exploit this success, they regrouped for The Horror Of Dracula (1958), a vibrant retelling of the Bram Stoker classic, decked out with lavish (if low budget) production values, a compelling performance by Lee as the vampire count, and workmanlike uncluttered direction from Terence Fisher. Once more the emphasis was on physical grue and violence though, by today’s standards, this early Hammer horror seems rather tame. But for the time, the formula worked marvelously, and for nearly two decades the studio produced a series of features which, for the most part, proved popular with international audiences. Cushing came back for the first Frankenstein sequel, The Revenge Of Frankenstein (1958), Lee made The Mummy (1959), and the two paired up for a splendid version of The Hound Of The Baskervilles (1959) in which Cushing gives a spirited performance as Sherlock Holmes while Lee portrayed Henry Baskerville.

While Hammer were scoring points with their Gothic remakes, one Hollywood producer was taking notice – Roger Corman. Throughout the fifties Corman directed all manner of exploitation films, from gangster melodramas to horror and science fiction thrillers. Some of the more lurid titles include The Day The World Ended (1955), It Conquered The World (1956), Attack Of The Crab Monsters (1956), Not Of This Earth (1956), The Undead (1956), The Viking Women And The Sea Serpent (1957), Teenage Caveman (1958), A Bucket Of Blood (1959), The Wasp Woman (1959), The Little Shop Of Horrors (1960), The Last Woman On Earth (1960) and Creature From The Haunted Sea (1960). As evidenced by this sampling of Corman titles, the young filmmaker made cheap quick pictures which satisfied the seemingly insatiable appetite of the mostly teenage audiences of the time. In some cases Corman churned out movies in just a matter of days on tiny budgets. From the beginning of 1955 to the end of 1960 he had directed no less than thirty-one features.

While Hammer were scoring points with their Gothic remakes, one Hollywood producer was taking notice – Roger Corman. Throughout the fifties Corman directed all manner of exploitation films, from gangster melodramas to horror and science fiction thrillers. Some of the more lurid titles include The Day The World Ended (1955), It Conquered The World (1956), Attack Of The Crab Monsters (1956), Not Of This Earth (1956), The Undead (1956), The Viking Women And The Sea Serpent (1957), Teenage Caveman (1958), A Bucket Of Blood (1959), The Wasp Woman (1959), The Little Shop Of Horrors (1960), The Last Woman On Earth (1960) and Creature From The Haunted Sea (1960). As evidenced by this sampling of Corman titles, the young filmmaker made cheap quick pictures which satisfied the seemingly insatiable appetite of the mostly teenage audiences of the time. In some cases Corman churned out movies in just a matter of days on tiny budgets. From the beginning of 1955 to the end of 1960 he had directed no less than thirty-one features.

With that amazing feat in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

With that amazing feat in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews