The coming of sound to the movies meant a great deal to the development of the fantasy genre. Although science fiction and particularly horror films had been produced since the earliest days of the medium, the addition of dialogue and, more importantly, special effects, greatly enhanced the creative abilities of filmmakers. As early as the turn of last century, Frenchman Georges Méliès had making short ‘trick’ films which had often been about or featured fantastic imagery. In 1902 Méliès made one of his most famous films, A Trip To The Moon (1902). This early cinematic pioneer can also be considered the first special effects maestro, creating a wealth of mechanical and optical illusions, with the latter being completely achieved in-camera without the benefit of post-production trickery.

In 1910, Thomas Edison produced the first of many versions of Frankenstein (1910). This ten-minute short had an electrifying effect on audiences of the era, despite the fact that many of the more horrific aspects of Mary Shelley’s novel were deleted from the film, soon after a film version of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (1912) appeared, the first of many. But it was in Europe during the second decade of last century and in the twenties that the horror film really had its beginning with such films as The Student Of Prague (1913) and The Golem (1917), Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari (1919) featured a story about a sleep-walking killer controlled by a mad doctor. The expressionistic sets, lighting and photography thrilled audiences and critics alike with its boldness. F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), based on Bram Stoker’s vampire classic Dracula, took the horrors one step further with its blend of realism and expressionism. Before we get stuck-in, I must profusely thank Wikipedia for assisting me with some research.

AELITA (1924): Also known as Queen Of Mars, Aelita was directed by Soviet filmmaker Yakov Protazanov and based on Alexaie Tolstoy‘s novel of the same name. Though the main focus of the story is the daily lives of a small group of people during the post-war Soviet Union, the enduring importance of the film really comes from its early science fiction elements. It primarily tells of a young man named Los, traveling to Mars in a rocket ship, where he leads a popular uprising against the ruling group of Elders, with the support of Queen Aelita who has fallen in love with him. This is very likely the first full-length movie involving space travel, the most notable part of the film remains its remarkable Martian sets and costumes designed by Aleksandra Ekster. Their influence can be seen in a number of later films, including the Flash Gordon serials and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926), and plot was also loosely adapted for Flight To Mars (1951). While very popular at first, the film later fell out of favour with the Soviet government and was thus very difficult to see until after the Cold War.

AELITA (1924): Also known as Queen Of Mars, Aelita was directed by Soviet filmmaker Yakov Protazanov and based on Alexaie Tolstoy‘s novel of the same name. Though the main focus of the story is the daily lives of a small group of people during the post-war Soviet Union, the enduring importance of the film really comes from its early science fiction elements. It primarily tells of a young man named Los, traveling to Mars in a rocket ship, where he leads a popular uprising against the ruling group of Elders, with the support of Queen Aelita who has fallen in love with him. This is very likely the first full-length movie involving space travel, the most notable part of the film remains its remarkable Martian sets and costumes designed by Aleksandra Ekster. Their influence can be seen in a number of later films, including the Flash Gordon serials and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926), and plot was also loosely adapted for Flight To Mars (1951). While very popular at first, the film later fell out of favour with the Soviet government and was thus very difficult to see until after the Cold War.

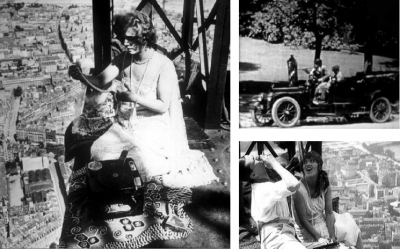

THE CRAZY RAY (1925): Also known as Paris Qui Dort (Paris Which Sleeps), The Crazy Ray is a French science fiction comedy directed by Rene Clair about a mad doctor who uses a magical ray on citizens which causes them to freeze in strange and often embarrassing positions. Not all the city’s inhabitants are frozen, however, a small number are mysteriously unaffected by the ray, and most of them take advantage of their position by breaking out of their social roles and having a darn good time. But the film’s young protagonist, a security guard on the Eiffel Tower, retains his sense of social responsibility and persuades the revelers to seek out the source of the phenomenon. Originally about an hour long, this was re-edited by Clair into a brisk 35 minutes in the fifties, and this is the version available as an extra on the Criterion DVD of Clair’s first sound feature, the engaging Under The Roofs Of Paris (1930), which features the same lead actor, Albert Préjean. Made with style and charm, the film still retains much of its humour when seen today.

THE CRAZY RAY (1925): Also known as Paris Qui Dort (Paris Which Sleeps), The Crazy Ray is a French science fiction comedy directed by Rene Clair about a mad doctor who uses a magical ray on citizens which causes them to freeze in strange and often embarrassing positions. Not all the city’s inhabitants are frozen, however, a small number are mysteriously unaffected by the ray, and most of them take advantage of their position by breaking out of their social roles and having a darn good time. But the film’s young protagonist, a security guard on the Eiffel Tower, retains his sense of social responsibility and persuades the revelers to seek out the source of the phenomenon. Originally about an hour long, this was re-edited by Clair into a brisk 35 minutes in the fifties, and this is the version available as an extra on the Criterion DVD of Clair’s first sound feature, the engaging Under The Roofs Of Paris (1930), which features the same lead actor, Albert Préjean. Made with style and charm, the film still retains much of its humour when seen today.

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1920): This is the best of many versions made during the silent era, and most of the talkie adaptations. In my own humble, subjective (yet always accurate) opinion, only the 1931 version starring Fredric March is better than this one. If you haven’t seen that version you should seek it out, but not before the conclusion of this article. I’m sure you’ll enjoy my old mate John Barrymore as yet another scientist who is punished for not knowing his place and tampering with the supernatural. He filmed this while preparing for a stage production of Richard The Third and it was a turning point in his film career. Prior to this his films were light-hearted action adventures such as The Incorrigible Dukane (1915) and Raffles (1916), but with the success of this multi-leveled performance, the studios cast him in more challenging roles. His triumphs continued into the sound era, for he had a most agreeable voice.

FAUST (1926): Starring Emil Jannings as Mephisto and Gosta Ekman as Faust, F.W. Murnau‘s film draws on older traditions of the legendary tale of Faust as well as Goethe’s classic version. The movie contains many memorable images and special effects, with careful attention paid to contrasts of light and dark. Particularly striking is the sequence in which the giant, horned and black-winged figure of Mephisto hovers over a town sowing the seeds of plague, an image later used by Walt Disney in Fantasia (1940). Faust was Murnau’s last film to be made in Germany, and he moved to the United States under contract to William Fox to direct Sunrise (1927). By the time Faust premiered in Berlin, Murnau was already shooting Sunrise in Hollywood.

FRAU IM MOND (1929): Also known as Woman On The Moon, this is considered by many to be the first serious science fiction film, directed by Fritz Lang and written by his then-wife and collaborator Thea von Harbou. The basics of rocket travel were presented to a mass audience for the first time by this film, including the use of a multi-stage rocket. The moon rocket (dubbed Friede) was submerged in water before launch, which NASA did not do when it sent actual rockets to the moon, but large rockets are launched over water to prevent damage to the spacecraft from the sound generated by liftoff. NASA did, however, have proposals for water-launched rockets. This film is often cited as the first occurrence of the countdown to zero before a rocket launch. The launch crew counts down the seconds from ten to zero and the rocket ship then blasts off into space. Since rocket scientist Hermann Oberth worked as an adviser on the movie, it was popular among the rocket scientists in Wernher von Braun’s circle, which is why the first V-2 rockets had the Die Frau Im Mond logo painted on the base!

THE GOLEM (1920): After making a version in 1914, Paul Wegener went on to make a series of fairy tales, but he returned to a longer and grander version of the Golem story in 1920. This second Golem (subtitled How He Came Into The World), which still exists in an 85-minute version, returned to the original story of Rabbi Loew, who creates the Golem to save the ghetto from disaster. The Rabbi is unable to control his creature, who resembles an incarnation of some juggernaut-like natural force. The Golem breaks through the ghetto gate into the world outside, where a pretty little Aryan girl (significantly) offers him an apple and then plucks the Star Of David from his chest, and he once again becomes no more than a dead clay statue. Young German maidens dance and play on the body, which is then ceremoniously carried back into the ghetto by the Jewish leaders.

THE GOLEM (1920): After making a version in 1914, Paul Wegener went on to make a series of fairy tales, but he returned to a longer and grander version of the Golem story in 1920. This second Golem (subtitled How He Came Into The World), which still exists in an 85-minute version, returned to the original story of Rabbi Loew, who creates the Golem to save the ghetto from disaster. The Rabbi is unable to control his creature, who resembles an incarnation of some juggernaut-like natural force. The Golem breaks through the ghetto gate into the world outside, where a pretty little Aryan girl (significantly) offers him an apple and then plucks the Star Of David from his chest, and he once again becomes no more than a dead clay statue. Young German maidens dance and play on the body, which is then ceremoniously carried back into the ghetto by the Jewish leaders.

LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (1927): Also known as The Hypnotist, London After Midnight is more like a mystery film with horror overtones. Produced and distributed by MGM, the film stars Lon Chaney Senior and was directed by Tod Browning. It is also a lost film, unfortunately, probably the most famous and eagerly-sought of all lost films. The last known copy was destroyed in a fire in a film vault in 1967. No copies of the film are known to exist, although there has been an attempt at a reconstruction utilising the screenplay and publicity photos. Chaney’s makeup for the film is noteworthy for the sharpened teeth and the hypnotic eye effect he achieved with special wire fittings which he wore like monocles. This was the only time Chaney used his famous makeup case as an on-screen prop. He purposefully gave the vampire character an absurd quality because, as it turns out, he was really a Scotland Yard detective (also played by Chaney) in disguise. Browning later remade the film with some changes as Mark Of The Vampire (1935) starring Lionel Barrymore and Bela Lugosi.

LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (1927): Also known as The Hypnotist, London After Midnight is more like a mystery film with horror overtones. Produced and distributed by MGM, the film stars Lon Chaney Senior and was directed by Tod Browning. It is also a lost film, unfortunately, probably the most famous and eagerly-sought of all lost films. The last known copy was destroyed in a fire in a film vault in 1967. No copies of the film are known to exist, although there has been an attempt at a reconstruction utilising the screenplay and publicity photos. Chaney’s makeup for the film is noteworthy for the sharpened teeth and the hypnotic eye effect he achieved with special wire fittings which he wore like monocles. This was the only time Chaney used his famous makeup case as an on-screen prop. He purposefully gave the vampire character an absurd quality because, as it turns out, he was really a Scotland Yard detective (also played by Chaney) in disguise. Browning later remade the film with some changes as Mark Of The Vampire (1935) starring Lionel Barrymore and Bela Lugosi.

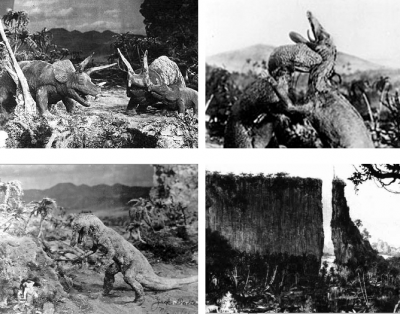

THE LOST WORLD (1925): The very first in-flight movie, The Lost World is an adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle‘s 1912 novel of the same name, and stars Wallace Beery as the excitable Professor Challenger. This version was directed by Harry Hoyt and features pioneering stop motion special effects by maestro Willis O’Brien. Many things in King Kong (1933) can be traced to earlier O’Brien projects such as The Lost World and his unfinished film Creation. For instance, the idea of a giant prehistoric monster running amuck in a modern city comes from O’Brien’s version of The Lost World, as does the log spanning a vast chasm which is then dislodged by a monster (an image used in both The Lost World and Creation), and the sequence where Kong reels in Ann Darrow and Driscoll as they attempt to climb down a vine is an elaboration of a similar sequence in The Lost World. Without a doubt, O’Brien contributed more to the overall structure of King Kong than he has been given credit for.

THE LOST WORLD (1925): The very first in-flight movie, The Lost World is an adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle‘s 1912 novel of the same name, and stars Wallace Beery as the excitable Professor Challenger. This version was directed by Harry Hoyt and features pioneering stop motion special effects by maestro Willis O’Brien. Many things in King Kong (1933) can be traced to earlier O’Brien projects such as The Lost World and his unfinished film Creation. For instance, the idea of a giant prehistoric monster running amuck in a modern city comes from O’Brien’s version of The Lost World, as does the log spanning a vast chasm which is then dislodged by a monster (an image used in both The Lost World and Creation), and the sequence where Kong reels in Ann Darrow and Driscoll as they attempt to climb down a vine is an elaboration of a similar sequence in The Lost World. Without a doubt, O’Brien contributed more to the overall structure of King Kong than he has been given credit for.

METROPOLIS (1927): Fritz Lang‘s science fiction classic is set in a futuristic urban dystopia and explores the social crisis between workers and owners in a capitalist society. The most expensive silent film ever made, it cost approximately five million Reichsmark, Metropolis features special effects and set designs that still impress modern audiences with their visual impact – the film contains cinematic and thematic links to German Expressionism although the architecture in the film appears to be based on contemporary Modernism and Art Deco. A new style in Europe at the time, Art Deco had not reached mass production yet and was considered an emblem of the bourgeois classes, and similarly associated with the ruling class in the film. Rotwang’s laboratory, with its lights and industrial machinery, is a forerunner of the Streamline Moderne style, highly influential on the look of laboratories of so-called mad scientists in popular culture. With many good performances, Brigitte Helm is the real star, portraying both the angelic Maria and her evil robot double.

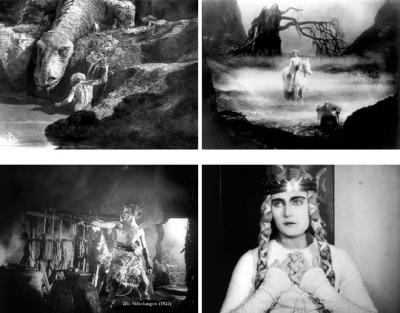

DIE NIBELUNGEN (1924): An epic silent fantasy film in two parts created by Austrian director Fritz Lang, entitled Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge. Both films were co-written by Lang’s then-wife Thea von Harbou, based on the epic poem Nibelungenlied written eight hundred years ago. Siegfried, the first part, is a marvel, one of the truly great silent films and one of the most spectacular ventures into fantasy and legend that there has ever been on the screen. It is best known for its stunning design work supervised by Lang himself, the vast sets and photography which owe less to expressionism than romanticism. But the characters are grand and the story exciting, subtle enough for adults and magical enough for kids. Kriemhild’s Revenge, the second part, is more sombre, more violent, more geared for adults. The visuals are equally as impressive and the character of Kriemhild, so passive in part one, becomes one of the most formidable heroines in film history. If you’ve been looking for a film in which Attila The Hun is a sympathetic figure (who respects women, is a good host, plays with babies, cries, etc.) then look no further.

DIE NIBELUNGEN (1924): An epic silent fantasy film in two parts created by Austrian director Fritz Lang, entitled Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge. Both films were co-written by Lang’s then-wife Thea von Harbou, based on the epic poem Nibelungenlied written eight hundred years ago. Siegfried, the first part, is a marvel, one of the truly great silent films and one of the most spectacular ventures into fantasy and legend that there has ever been on the screen. It is best known for its stunning design work supervised by Lang himself, the vast sets and photography which owe less to expressionism than romanticism. But the characters are grand and the story exciting, subtle enough for adults and magical enough for kids. Kriemhild’s Revenge, the second part, is more sombre, more violent, more geared for adults. The visuals are equally as impressive and the character of Kriemhild, so passive in part one, becomes one of the most formidable heroines in film history. If you’ve been looking for a film in which Attila The Hun is a sympathetic figure (who respects women, is a good host, plays with babies, cries, etc.) then look no further.

NOSFERATU (1922): The name itself is enough to induce an excrement hemorrhage in anyone who watched this movie during their youth, like I did. I mean, those fingernails! He clearly isn’t getting regular manicures, and Nosferatu had the shaved-head look long before it was trendy. Overall, it’s one fine piece of cinema. The film stars the aptly named Max Schreck as the vampire. Schreck, in case you weren’t aware of it, is the German word meaning ‘fear’. How cool is that? Schreck was a Stanislovsky method actor, which meant that he immersed himself fully in the character – as well as the unconsecrated soil of Transylvania. He was so effective that some on the set of Nosferatu believed that Schreck might actually be a vampire. This conceit was later used in Shadow Of The Vampire (2000) starring John Malkovich as Murnau and Willem Dafoe as Max Schreck, a vampire pretending to be an actor.

NOSFERATU (1922): The name itself is enough to induce an excrement hemorrhage in anyone who watched this movie during their youth, like I did. I mean, those fingernails! He clearly isn’t getting regular manicures, and Nosferatu had the shaved-head look long before it was trendy. Overall, it’s one fine piece of cinema. The film stars the aptly named Max Schreck as the vampire. Schreck, in case you weren’t aware of it, is the German word meaning ‘fear’. How cool is that? Schreck was a Stanislovsky method actor, which meant that he immersed himself fully in the character – as well as the unconsecrated soil of Transylvania. He was so effective that some on the set of Nosferatu believed that Schreck might actually be a vampire. This conceit was later used in Shadow Of The Vampire (2000) starring John Malkovich as Murnau and Willem Dafoe as Max Schreck, a vampire pretending to be an actor.

THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE (1926): Henrik Galeen‘s remake of the 1913 film of the same name is considered his most important film since The Golem (1915) which he co-directed in 1915 with Paul Wegener. In the meantime, Galeen had written The Golem (1920), Nosferatu (1922) and Waxworks (1924). This probably represents the last gasp of German romantic Gothic cinema, extremely stylish with wild, almost expressionistic sets. Scapinelli (Werner Krauss) is the umbrella-wielding bourgeois devil who buys the soul of Baldwin (Conrad Veidt) in exchange for his reflection in a mirror. The reflection then becomes a Doppelganger, a phantom double which haunts Baldwin until driven to suicide.

THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (1924): This swashbuckler from director Raoul Walsh starred Douglas Fairbanks Senior and tells the story of a thief who falls in love with the daughter of the Caliph. Strong on special effects of the period (flying carpets, magic urns and fearsome monsters) and featuring massive exotic-looking sets, the film also proved a stepping stone for a scantily-clad Anna May Wong as a Mongol slave. According to Douglas Fairbanks Junior, his dad considered this to be his personal favourite of all of his films. The use of imaginative gymnastics fit the athletic star, his catlike, seemingly effortless movements were as much dance as gymnastics.

Also: see

1930s Genre Films

1940s Genre Films

1950s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1970s Genre Films

1980s Genre Films

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews