We might be united by the colour of our blood but humans are changeable within just a few miles of each other. There’s an accent or two for every county in the UK, different ways of referring to food, objects, and each other, and a regional football heritage that could turn hostile at any moment. We’re still living in the clans of old, albeit safe inside from the worst of the British winter.

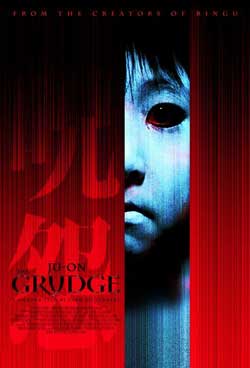

“Forboding Silence”

This goes for the rest of the world, too. Cultural differences aren’t always about flesh and the gooey stuff. Tastes in music and entertainment vary between borders, while different attitudes to business sometimes produce granular changes in how games are played. The classic example is roulette, which has a single zero in Europe but two zeroes in its American variant, potentially making European Roulette real money friendlier to the player’s bankroll.

Similarly, the distinction in how fans appreciate their horror – in cellulose or on paper – changes with latitude and longitude. Japanese horror director Takashi Shimizu (of 2004’s Ju-On: The Grudge) notes that American viewers prefer “surprising” scenes while their Eastern counterparts like to be slowly scared. The obvious culprit on the former side is the jump scare, which – ironically – relieves tension.

Shimizu continued to describe American horror as “masculine”, leading with violence, gore, and the risk of “being eaten”. Conversely, Japanese audiences get their chills from psychological themes or the fear hidden in a “forboding silence”. This might include paranormal entities doing nothing other than standing in the corner. It’s what our ghost is feeling – anger, sadness, fear – that torments Japanese fans.

‘Bottle Episode’

UK cinema is different once again. The Guardian describes its native horror as “gritty realism”. Movies like Shaun of the Dead (2004), Creep (2004), and The Descent (2005) are low-budget efforts that, in the former case, took the concept of a zombie apocalypse – usually a global affair in Hollywood – and placed it in locations Brits would find eerily familiar, like a living room or a newsagent.

In a sense, UK horror encapsulated the idea of a ‘bottle episode’, an American term describing a regular season piece that’s made with as few characters, locations, and money as possible.

Battlestar Galactica’s Unfinished Business is a good example, taking place solely within a boxing ring yet managing to demonstrate the crew’s fraught relationships. Breaking Bad’s Fly shows Walter White’s collapsing psyche without leaving a single room. There’s also James Wan’s Saw (2004), which is set mostly in a public bathroom.

Perhaps the strongest indicator of UK horror is something the US struggles to present authentically – gothic themes, an unlikely mix of horror, desolation, and romance. British director Simon Sprackling told the Guardian the UK has a “proper gothic tradition” coloured by our natural “fatalism”, the idea that nothing will ever truly work out in the end.

There’s much to be said for the UK film industry having less money than Hollywood to throw at niche productions but, like Alien (1979), which made US$100m+ on a budget of US$11m, money isn’t always the root of real horror.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews