In June 1993, Jurassic Park celebrated its twenty-seventh birthday—that’s an entire lifetime for an actual T-Rex. Despite huge advances in CGI technology, a slew of imitators and a parade of sequels, Jurassic still stands tall as the quintessential modern dinosaur movie, unmatched in terms of unbridled fun and excitement. But, in truth, Jurassic Park’s Dino-DNA contains a few notable filmic ancestors, each of which changed the face of cinema.

To earn a place on Jurassic’s family tree a film must be a box office hit that included multiple dinosaurs and, in its own way, altered the pop culture landscape. That criteria thinned the herd from a few hundred films to only four and a half. That “half” rating will make sense in part three.

So, join me for a stroll down the Road to Jurassic Park.

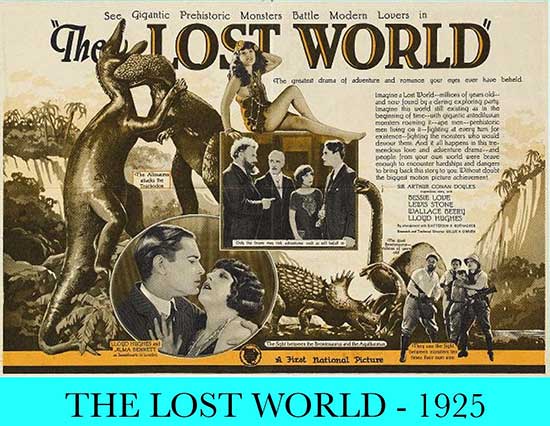

This adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s eponymous book forged the template for every dinosaur movie that followed. If you’re already clicking on YouTube to check out this silent classic, please bear in mind that it was made nearly a hundred years ago, so adjust your technical and social expectations accordingly.

Rogue scientist Professor Challenger comes into possession of a missing explorer’s diary, detailing his adventures on a previously undiscovered plateau where dinosaurs still roam. Challenger mounts an expedition to uncover this lost world, accompanied by the lost explorer’s daughter and a journalist, along with some jungle movie stereotypes. Low and behold, our intrepid adventurers discover living dinosaurs… And that was the moment that blew audiences’ minds!

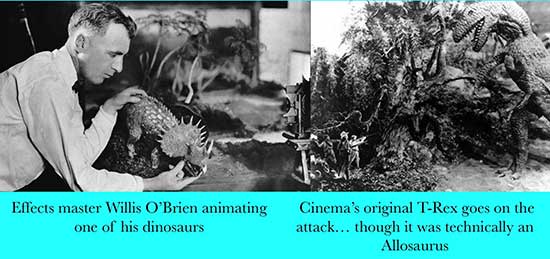

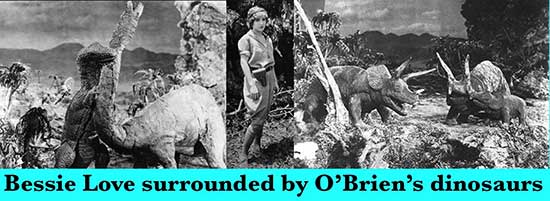

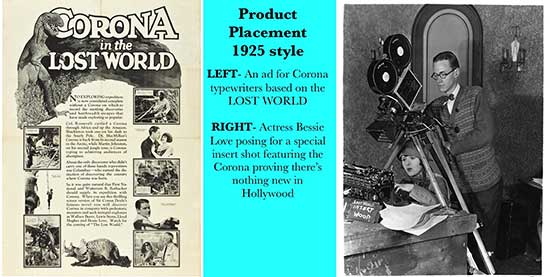

Willis O’Brien’s intricate stop motion animation brought terrifying prehistoric monsters to life. Up to this point the special effects pioneer had only created short dinosaur films like The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918). These shorts often downplayed the terror in favor of comedy, but with The Lost World, O’Brien went straight for the thrills, brilliantly combining his animated dinosaurs with live action. The climactic scenes of a brontosaurus tearing through modern London sent terrified audiences running for the exits. Okay, that statement might have just been Hollywood press ballyhoo, but the scene is genuinely amazing.

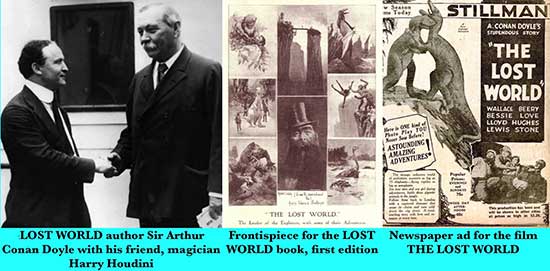

Everyday moviegoers weren’t the only ones fooled by the effects. Before its release, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself screened footage for members of New York’s Society of American Magicians, including Harry Houdini no less. The audience of professional illusionists were mystified and, after seeing the footage, the New York Times declared that, “If fakes, they were masterpieces.”

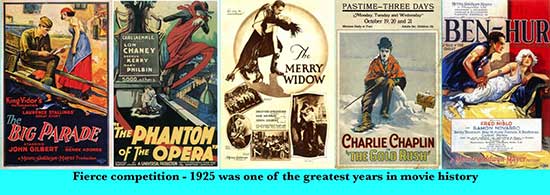

The Lost World was the eighth most popular film of 1925, but it was up against six movies that are considered classics—De Mille’s Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ, King Vidor’s The Big Parade, Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, Von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow and Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman along with Lon Chaney’s The Phantom of the Opera. You really got your quarter’s worth buying a movie ticket back in 1925!

While the special effects are extraordinary the live action scenes are less than stellar. Harry O. Hoyt’s direction harkens back to the previous decade, with long, static scenes and little camera movement. Compare The Lost World’s dramatic scenes to 1925’s other hits and it feels … well, prehistoric. Hoyt even cut to revealing the dinosaurs without buildup or pomp. Hoyt’s later career trajectory was as lukewarm as his direction, ending with low-budget westerns and Buck Jones serials.

Top-billed Wallace Beery does a great job chewing the scenery as Professor Challenger. Beery is somewhat forgotten today, but at that time he was one of Hollywood’s highest paid actors. He was still busy acting and dodging paternity suits up until his death in 1949.

There are only two female characters, and the gender roles are very much of their time. First we meet the hero’s superficial fiancée who refuses to wed him until he performs some manly, heroic deed. After that stereotype we’re introduced to the film’s main heroine, Paula White. She bravely makes the trek to find her missing father but spends much of her screen time fainting and screaming. It’s disappointing, but the 1960 Irwin Allen remake actually sank from merely condescending into outright misogyny, with jaw dropping lines like, “The best title for a woman is still Mrs.”

And speaking of things that are “of their time,” there’s the unfortunately named native gun bearer Zambo, played by white actor Jules Cowles in horrendous blackface. Cowles made a career out of playing blackface roles up until the 1940s, when Hollywood finally consented to let actual African Americans portray demeaning African American stereotypes.

But when those dinosaurs hit the screen, everything, except for the blackface, is forgiven. The only thing that kept the dinosaurs from truly coming alive was their silence … but that was about to change.

There’s just so much right about King Kong that it’s impossible to summarize. It’s a rousing adventure, an incredible dinosaur film, and a star-crossed romance with cinema’s most memorable closing line. On the technical side, Kong invented the modern film score and revolutionized sound design. It also packs in plenty of pre-code violence and eroticism and even elevated a recently constructed Manhattan office building into the American Taj Mahal. King Kong is a testament to just how many correct decisions can be made on one movie.

In part two we’ll explore the creative elements the made King Kong into the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World.’ And if you’re feeling hungry for giant monster thrills check out my new novel Scorpius Rex, published by those undisputed masters of Kaiju fiction at Severed Press. Available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews