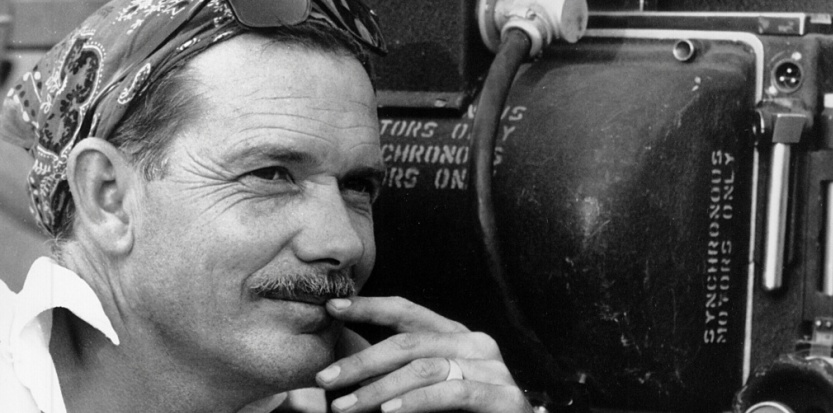

Since 1967 a number of American filmmakers have tried their hand at making movies of great violence that have managed to further refine the complexity of the statement contained in the groundbreaking big-budget Hollywood blockbuster Bonnie And Clyde (1967). One filmmaker who earned his ‘Red Badge’ is Sam Peckinpah who, like Arthur Penn and John Frankenheimer, can be seen as part of the American sixties ‘new wave’ – young directors who came into movies via television instead of working up through the old Hollywood studio system.

Peckinpah had learned something about American films that the ‘new wave’ in Europe, like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, had learned: All American films with anything to say were violent. The movies of both Truffaut and Godard depicted archetypes of earlier American gangster films, and made their new syntax the violent acts of these men.

Born and raised on a ranch in California, Peckinpah attended military school and had a spell in the Marines. His films reflect his background, a masculine world where one’s manhood and independence can only survive through violence, the nostalgic Old West, when men were men and women were seen and not heard. No matter how unpalatable one may find this philosophy, he expresses it with passionate intensity.

Born and raised on a ranch in California, Peckinpah attended military school and had a spell in the Marines. His films reflect his background, a masculine world where one’s manhood and independence can only survive through violence, the nostalgic Old West, when men were men and women were seen and not heard. No matter how unpalatable one may find this philosophy, he expresses it with passionate intensity.

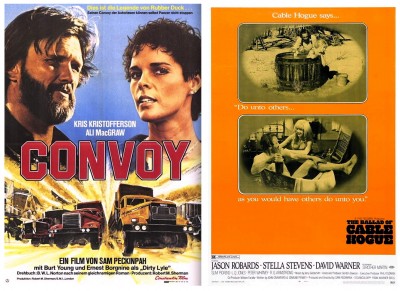

The recurring theme of ‘Unchanged men in a changing land’ appears in Ride The High Country aka Guns In The Afternoon (1962) with Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea as aging gunfighters escorting a cargo of gold has more to do with nostalgia for old western films rather than the Old West itself. In The Wild Bunch (1969), William Holden and his gang try to live as outlaws from another age, although the scenes of carnage reflect the year the film was made. The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970) is another elegy to the Old West and, in Junior Bonner (1972), Steve McQueen feels like an anachronism in the modern West. He tries to scrape together a living as a rodeo rider while his brother makes money by selling properties and exploiting the Old West for its tourism possibilities. In the end, his father (Robert Preston) leaves for Australia where he hopes to find some of the forgotten frontier values.

The recurring theme of ‘Unchanged men in a changing land’ appears in Ride The High Country aka Guns In The Afternoon (1962) with Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea as aging gunfighters escorting a cargo of gold has more to do with nostalgia for old western films rather than the Old West itself. In The Wild Bunch (1969), William Holden and his gang try to live as outlaws from another age, although the scenes of carnage reflect the year the film was made. The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970) is another elegy to the Old West and, in Junior Bonner (1972), Steve McQueen feels like an anachronism in the modern West. He tries to scrape together a living as a rodeo rider while his brother makes money by selling properties and exploiting the Old West for its tourism possibilities. In the end, his father (Robert Preston) leaves for Australia where he hopes to find some of the forgotten frontier values.

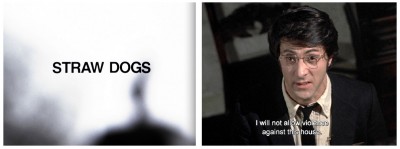

Peckinpah’s westerns, photographed superbly by Lucian Ballard, splattered with blood and symbols, have a lyrical detachment. With an amazing CV that includes Major Dundee (1963), The Getaway (1972), Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid (1973), The Killer Elite (1975), Cross Of Iron (1977), Convoy (1978) and The Osterman Weekend (1983), Peckinpah’s career has always been associated with its own myth of a grizzled and permanently embattled movie veteran who doesn’t mind taking on the front office when it suits him, but Peckinpah has made only one movie of detailed substance which also happened to be filmed in England: Straw Dogs (1971) starring Dustin Hoffman and Susan George with a screenplay by Waldo Salt based on the Gordon Williams novel The Siege Of Trencher’s Farm.

Straw Dogs tells the story of a clever young American scientist (mathematics, astrophysics, it’s not made clear) who settles in a Cornish cottage for the summer with his beautiful but bored young wife, on sabbatical from the campus with a research project to complete. David, whose amiable and engaging personality Hoffman catches very accurately, is a man who likes to work and then play. There’s not a great deal he requires besides his all-engrossing research: A little peace, a little loving. There’s a suggestion early on that he might be working hard to avoid certain unpleasant aspects of life, the campus confrontation back home, for instance, which his wife refers to rather scathingly, as though she wishes David had taken sides instead of running away. But Hoffman’s performance is so agreeably sane that he neutralises the director’s intentions, suggesting instead that he’s too wise to ever get involved in such madness.

Straw Dogs tells the story of a clever young American scientist (mathematics, astrophysics, it’s not made clear) who settles in a Cornish cottage for the summer with his beautiful but bored young wife, on sabbatical from the campus with a research project to complete. David, whose amiable and engaging personality Hoffman catches very accurately, is a man who likes to work and then play. There’s not a great deal he requires besides his all-engrossing research: A little peace, a little loving. There’s a suggestion early on that he might be working hard to avoid certain unpleasant aspects of life, the campus confrontation back home, for instance, which his wife refers to rather scathingly, as though she wishes David had taken sides instead of running away. But Hoffman’s performance is so agreeably sane that he neutralises the director’s intentions, suggesting instead that he’s too wise to ever get involved in such madness.

His wife, however, is made of different stuff. She’s no stranger to this remote corner of Cornwall. She knows the local boys, all of whom fancy her hard, more brutally lustful than they would be if she hadn’t married a sneaker-wearing Yankee professor with a white sports car. It’s clear that one of the local lads feels entitled, since he had her when she was here years before. At first we feel that perhaps she is being victimised by them, but it’s not long before we realise she is that familiar screen archetype, the Cocktease, and has her own problems of which David seems unaware. While she’s flirting with the lads, who have inveigled their way into the house on the pretext of mending the garage roof, David watches from his study window. It is nothing as direct as complicity, but there is something unhealthy going on, and David chooses not to notice the implications: His wife is locking into a weird game with the louts who hate him.

His wife, however, is made of different stuff. She’s no stranger to this remote corner of Cornwall. She knows the local boys, all of whom fancy her hard, more brutally lustful than they would be if she hadn’t married a sneaker-wearing Yankee professor with a white sports car. It’s clear that one of the local lads feels entitled, since he had her when she was here years before. At first we feel that perhaps she is being victimised by them, but it’s not long before we realise she is that familiar screen archetype, the Cocktease, and has her own problems of which David seems unaware. While she’s flirting with the lads, who have inveigled their way into the house on the pretext of mending the garage roof, David watches from his study window. It is nothing as direct as complicity, but there is something unhealthy going on, and David chooses not to notice the implications: His wife is locking into a weird game with the louts who hate him.

This plot connects with a subplot set in the village, where the village idiot (David Warner) wanders about annoying the locals, in particular the village elder played by Peter Vaughan in a suitably sinister fashion. On the night of the village hall dance, the idiot accidentally strangles a local girl while trying to keep her quiet. He runs away knowing the louts will kill him when they find out and, on the mist-covered roads, is knocked down by David’s car. David takes him home to phone for a doctor but, when word reaches the village that the Yank is harbouring the killer, the elder and his louts set out with a shotgun to have their revenge. Among the group are the three who, in an earlier scene, subjected David’s wife to a curious form of semi-rape, having lured David away on a dummy duck shoot.

David, however, knows nothing of this, and indeed never does find out. The gang, finding that David will not simply relinquish his guest to be torn to pieces by them, besiege the cottage. Now David has no choice, he has to kill them or they will kill him, his wife and the child-man locked in his attic. By the end of the film all the ‘cavemen’ lie dead, one with his head in the vicious bear-trap he had taught David to set, the last of them gunned down by David’s wife as he tries to murder David. Then David drives away with the child-man, leaving the girl, who has had to become a woman, left alone among the carnage. “I don’t know where we are,” whispers the child-man. “Nor do I,” says David, as the mists of trauma close around them.

David, however, knows nothing of this, and indeed never does find out. The gang, finding that David will not simply relinquish his guest to be torn to pieces by them, besiege the cottage. Now David has no choice, he has to kill them or they will kill him, his wife and the child-man locked in his attic. By the end of the film all the ‘cavemen’ lie dead, one with his head in the vicious bear-trap he had taught David to set, the last of them gunned down by David’s wife as he tries to murder David. Then David drives away with the child-man, leaving the girl, who has had to become a woman, left alone among the carnage. “I don’t know where we are,” whispers the child-man. “Nor do I,” says David, as the mists of trauma close around them.

The character of David lies at the core of the film. The savagery in Straw Dogs is especially affecting because it streams out of the ‘cavemen’ to be refracted back at them from this amiable man who has had to learn to be a killer overnight. David is that rare animal in cinema: The intellectual hero. What Peckinpah does is mesh two archetypes – the Killer and the Wise Man – into one character. David is one of the first screen intellectuals to be fully dimensionalised within the area of total violence. He is the common ground between you who read this and I who write it, for his is the kind of person many of like to think we are – too intelligent to be drawn naturally to violence since, like us, he knows that those who live by the gun die by the gun.

A man who has grown up since World War Two inside the blossom of his intellect, inside the relative safety of the college campus, closeted by the security of pursuing ideas that interest him. ‘Violence’ is a system he never had to learn, for violence is the expression of our unconscious selves, and this frustration does not exist for David. He’s depicted as a man who is a long way into himself, and there is a telling shot as he sits on a garden swing, rocking in a self-communing idyll over his notebook, doodling deep into his inner systems, until his wife decides that what he needs – since he’s sitting on a swing – is to be pushed.

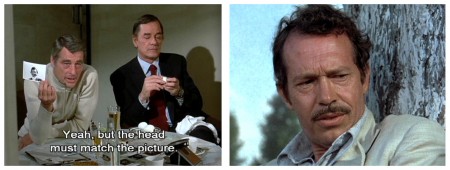

Speaking of swings, Peckinpah took a swing-and-a-miss with Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia (1974) starring Warren Oates as an embittered loser who hears of a ten thousand dollar bounty on a man named Garcia and goes to find him or, more accurately, goes to find Garcia’s head, which is required in order to claim the bounty. After various misadventures – including the rape and murder of the girl he loves – he brings the severed head in a flyblown sack back to the city. But it’s not the ten thousand dollars he’s after, no, he’s sharp enough to know that this is just the beginning: He guns down several more hoodlums and goes after the big money, a cool million, which has been offered as a reward by a Mexican nobleman whose daughter has been impregnated by the late Garcia. Oates arrives, drops the head on the table and states the film’s body-count: “Sixteen men have died for this.”

Speaking of swings, Peckinpah took a swing-and-a-miss with Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia (1974) starring Warren Oates as an embittered loser who hears of a ten thousand dollar bounty on a man named Garcia and goes to find him or, more accurately, goes to find Garcia’s head, which is required in order to claim the bounty. After various misadventures – including the rape and murder of the girl he loves – he brings the severed head in a flyblown sack back to the city. But it’s not the ten thousand dollars he’s after, no, he’s sharp enough to know that this is just the beginning: He guns down several more hoodlums and goes after the big money, a cool million, which has been offered as a reward by a Mexican nobleman whose daughter has been impregnated by the late Garcia. Oates arrives, drops the head on the table and states the film’s body-count: “Sixteen men have died for this.”

Then, at the behest of the dishonoured daughter, he executes the new owner of the severed head, thus becoming a patsy twice over: Firstly in the grip of the nobleman’s revenge scenario, secondly in the grip of the daughter’s. He then rides away only to be gunned down at the gates, the camera coming to rest on a gun barrel as Mr. Peckinpah’s credit appears next to it. The difference in objectivity between Straw Dogs and Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia is remarkable. Keep that thought in mind until we meet again next week when I have another opportunity to inflict a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense that it shocks the brain into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![StrawDogs_Blu-ray[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/StrawDogs_Blu-ray1-e1315008980485-310x165.jpg)