“1940: pacifist ideals are threatened when the ‘United States of Europe’ comes into conflict with the ‘Empire of the Atlantic States’. In the film the prohibition era in America continues and the tension is initially caused by bootleggers crossing the borders between territories. One such incident leads to a shoot-out between border guards in which both sides suffer casualties. War looks likely, but the pacifist Peace League intervenes. Meanwhile, we learn that the tension is in fact carefully orchestrated by a sinister terrorist group financed by arms manufacturers. They blow up a rail tunnel under the English Channel. The President of Europe orders a mass enlistment and mobilisation, fearing that the Atlantic States are preparing a sneak attack. Dr. Seymour, leader of the Peace League, desperately attempts to avert war. His daughter Evelyn attempts to convince her boyfriend Michael, commander of the European air force, not to fight but he insists he must do his duty. Evelyn says she will leave him. The European council are divided, but the president decides on war, saying that he will announce the outbreak of hostilities on television. The terrorists try to kill Dr. Seymour by bombing the Peace League, but Seymour survives. He tells Evelyn to make another effort to stop Michael ordering the airforce to attack, while he appeals directly to the President. Pacifists led by Evelyn demonstrate en masse at the airfield. Michael is uncertain what to do, but Evelyn convinces him to delay the attack. Seymour confronts the President, but is forced, despite his pacifism, to shoot him to stop him making the broadcast.” (courtesy Wikipedia)

REVIEW:

The discovery by the film studios that audiences actually wanted sound – that they preferred talkies to silent films – panicked the studios during the late twenties and, almost overnight, the style of movies changed. The fluid visuals of the typical silent film were replaced by static scenes in which the actors, no longer able to venture outdoors, huddled together in rooms and talked into plants or articles of furniture containing the all-important microphone – and talked and talked and talked. The problem lay in finding something for them to talk about – in silent films many performers simply moved their mouths, repeating words like ‘rhubarb’ or mouthing the alphabet. All of a sudden film-scenario writers were required to fill countless pages with dialogue, which is unfortunate as many of them weren’t even capable of writing their own names, let alone an entire hour or more of dialogue.

Frantic film producers started looking elsewhere for suitable talkie material, and very quickly discovered the theatre. It seemed like the ideal solution because, in stage plays, they learned there was always a lot of talk and, more importantly, took place mostly indoors. This meant that, for a time, films relying on visual spectacle fell out of fashion. Willis O’Brien, for instance, was unable to generate any interest in his animation projects for several years. In retrospect, it might look as if the time was ripe for the genre film to evolve into something more sophisticated, to become a platform of ideas rather than merely a showcase for special effects – my old friend H.G. Wells was certainly interested in using films this way – but sadly this development did not take place. Filmmakers soon realised that it was possible to combine sound and spectacle, so the cinema once again reverted to its normal low-minded self, with the emphasis once again on action rather than ideas.

Frantic film producers started looking elsewhere for suitable talkie material, and very quickly discovered the theatre. It seemed like the ideal solution because, in stage plays, they learned there was always a lot of talk and, more importantly, took place mostly indoors. This meant that, for a time, films relying on visual spectacle fell out of fashion. Willis O’Brien, for instance, was unable to generate any interest in his animation projects for several years. In retrospect, it might look as if the time was ripe for the genre film to evolve into something more sophisticated, to become a platform of ideas rather than merely a showcase for special effects – my old friend H.G. Wells was certainly interested in using films this way – but sadly this development did not take place. Filmmakers soon realised that it was possible to combine sound and spectacle, so the cinema once again reverted to its normal low-minded self, with the emphasis once again on action rather than ideas.

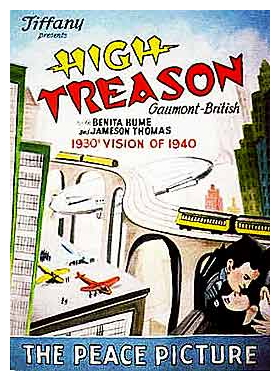

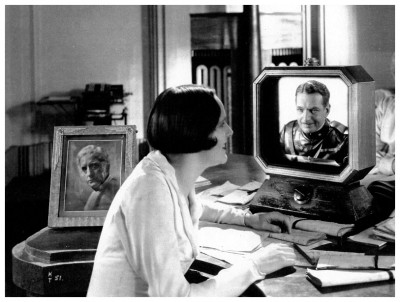

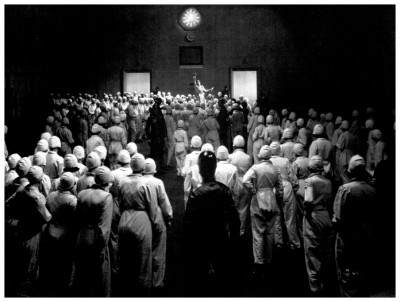

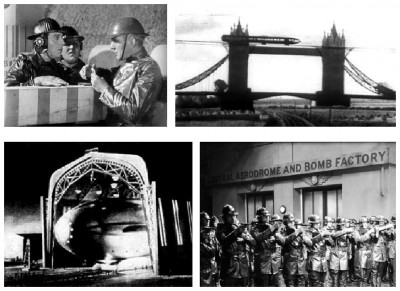

In the intervening period, however, came a science fiction talkie that took itself very seriously indeed. High Treason (1929) was made in Britain, based on a stage play by Pemberton Billing which reflected the strong pacifist movement in Europe between the two world wars. It takes place in the far-flung future year of 1940, when the two most powerful political alliances on the globe are called the United Atlantic States and the Federated States Of Europe. They are in danger of declaring war on each other, so 25 million people of all nationalities have formed the Peace League to try and prevent such a thing from happening. When an argument breaks out between two soldiers over a card game at the frontier threatens to spark-off the feared holocaust after the Peace League building has been bombed, the President of the Peace League assassinates the President of the European States to prevent him from declaring war. He then makes a global television broadcast which conciliates the Atlantic States and successfully averts bloodshed. The film ends with him bravely facing execution for the murder of the European leader.

In the intervening period, however, came a science fiction talkie that took itself very seriously indeed. High Treason (1929) was made in Britain, based on a stage play by Pemberton Billing which reflected the strong pacifist movement in Europe between the two world wars. It takes place in the far-flung future year of 1940, when the two most powerful political alliances on the globe are called the United Atlantic States and the Federated States Of Europe. They are in danger of declaring war on each other, so 25 million people of all nationalities have formed the Peace League to try and prevent such a thing from happening. When an argument breaks out between two soldiers over a card game at the frontier threatens to spark-off the feared holocaust after the Peace League building has been bombed, the President of the Peace League assassinates the President of the European States to prevent him from declaring war. He then makes a global television broadcast which conciliates the Atlantic States and successfully averts bloodshed. The film ends with him bravely facing execution for the murder of the European leader.

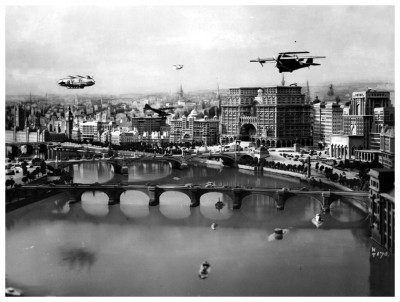

Directed by Maurice Elvey, who had started directing in 1912 and later went on to make the English-language version of The Tunnel (1935), it attracted favourable critical comment, particularly in the United Kingdom, where one reviewer wrote: “It confirms the impression that the talking picture is the medium in which Britain is qualified to lead the world. Comparisons with the great German film Metropolis (1927) will naturally arise but, as popular entertainment, such comparisons must be in favour of the British film. The forecast of London and New York in the future shows imagination of design within the bounds of possibility, and steers clear of the exaggerated phantasy of Metropolis. Neither has Mr. Elvey relied overmuch on tricks of the camera. The lighting is effective and the sensational scenes of the flooding of the channel tunnel and the destruction by bombs of the Peace League building are most realistic and impressive.”

Directed by Maurice Elvey, who had started directing in 1912 and later went on to make the English-language version of The Tunnel (1935), it attracted favourable critical comment, particularly in the United Kingdom, where one reviewer wrote: “It confirms the impression that the talking picture is the medium in which Britain is qualified to lead the world. Comparisons with the great German film Metropolis (1927) will naturally arise but, as popular entertainment, such comparisons must be in favour of the British film. The forecast of London and New York in the future shows imagination of design within the bounds of possibility, and steers clear of the exaggerated phantasy of Metropolis. Neither has Mr. Elvey relied overmuch on tricks of the camera. The lighting is effective and the sensational scenes of the flooding of the channel tunnel and the destruction by bombs of the Peace League building are most realistic and impressive.”

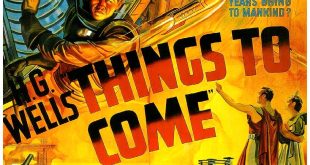

All of which reads like embarrassing chauvinism today, especially since High Treason – with its dated sermonising – has been all but forgotten while the timeless Metropolis still proves its popularity with audiences. Nor can the basic contradiction in the film’s pacifist message be easily overlooked: The leader of the peace group has to become a murderer to achieve his pacifist aims. That sort of behaviour gives pacifism a bad name. The vision of the future offered in High Treason is an ambivalent one. On one hand, the people we meet appear perfectly content and satisfied, with plenty of leisure time and access to technology that enhances their lifestyle without being intrusive, implying that class differences no longer exist. On the other hand, there is an element of coldness, repetition and automation that, by today’s standards at least, would be considered fairly negative in its lack humanity and individuality. Thanks to solid acting by the likes of Humberston Wright and Basil Gill – and an uncredited short appearance by Raymond Massey in his first role seven years before he would play the role of John Cabal in Things To Come (1936) – High Treason is one of the best examples of early science fiction cinema.

All of which reads like embarrassing chauvinism today, especially since High Treason – with its dated sermonising – has been all but forgotten while the timeless Metropolis still proves its popularity with audiences. Nor can the basic contradiction in the film’s pacifist message be easily overlooked: The leader of the peace group has to become a murderer to achieve his pacifist aims. That sort of behaviour gives pacifism a bad name. The vision of the future offered in High Treason is an ambivalent one. On one hand, the people we meet appear perfectly content and satisfied, with plenty of leisure time and access to technology that enhances their lifestyle without being intrusive, implying that class differences no longer exist. On the other hand, there is an element of coldness, repetition and automation that, by today’s standards at least, would be considered fairly negative in its lack humanity and individuality. Thanks to solid acting by the likes of Humberston Wright and Basil Gill – and an uncredited short appearance by Raymond Massey in his first role seven years before he would play the role of John Cabal in Things To Come (1936) – High Treason is one of the best examples of early science fiction cinema.

Fast-forward to 1998, a new sound version of High Treason was produced by the combined efforts of the French electronica duo Les Electrons Libres and La Cinémathèque de Toulouse film archive. The archive supplied the duo with a version that runs a full 71 minutes, which was successfully screened at film festivals in Paris, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Rennes and Barcelona. At this point I’ll make my farewells, but not before profusely thanking The Bioscope magazine (14th August 1927) for assisting my research for this article. Consider yourself graciously invited to join me next week when I will take you even closer to the event horizon of that insatiable black hole known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Fast-forward to 1998, a new sound version of High Treason was produced by the combined efforts of the French electronica duo Les Electrons Libres and La Cinémathèque de Toulouse film archive. The archive supplied the duo with a version that runs a full 71 minutes, which was successfully screened at film festivals in Paris, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Rennes and Barcelona. At this point I’ll make my farewells, but not before profusely thanking The Bioscope magazine (14th August 1927) for assisting my research for this article. Consider yourself graciously invited to join me next week when I will take you even closer to the event horizon of that insatiable black hole known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews