In the current climate of rampant digital effects, ultra-real prosthetics and virtual 3-D cinematography, audiences are being spoiled.

In the current climate of rampant digital effects, ultra-real prosthetics and virtual 3-D cinematography, audiences are being spoiled.  Special effects have become commonplace and of such a high standard that jaws are no longer dropping. This wasn’t always so. Special effects have come a long way since the invention of cinema and the path they have walked is fascinating.

Special effects have become commonplace and of such a high standard that jaws are no longer dropping. This wasn’t always so. Special effects have come a long way since the invention of cinema and the path they have walked is fascinating.

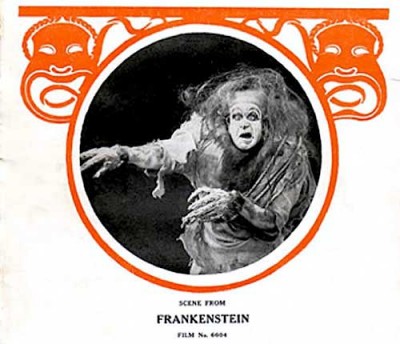

Arguably, the first film ever made was called Fred Ott’s Sneeze and was made, funnily enough, by Fred Ott and Thomas Edison in 1893 (I actually met Tom Edison back in 1910 when I played Charles Ogle‘s body double in the creation scene in Frankenstein (1910).

I didn’t find out until after I signed the contract that Frankenstein’s monster would be ‘born-into-fire’. My screams of agony and arm-waving was all but ignored by Mr. Edison, who just said “Keep rolling!” but that’s another story for another time).

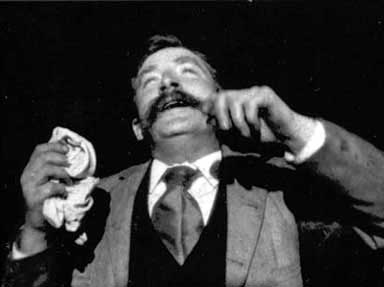

The first special effect appeared three years later in 1895 with The Execution Of Mary Queen Of Scots (1895) – consisting of the camera being stopped and the actress being replaced by a dummy which was then beheaded – closely followed by The Sausage Machine (1895) – in which dogs and cats are fed in at one end of the machine and come out at the other as linked sausages. This is a far cry from modern special effects, but they’re the earliest recorded instances of the camera being used to film anything other than undiluted reality.

Then came Georges Méliès. Méliès was a magician, actor and theatre designer, and in 1896 opened the first film studio in Paris, called Montreuil-sous-Bois. The next year he released his first picture L’Auberge Ensorcelee (1897), in which a man (Méliès himself) is frightened when his clothes disappear, his boots walk unaided and his furniture collapses.

Then came Georges Méliès. Méliès was a magician, actor and theatre designer, and in 1896 opened the first film studio in Paris, called Montreuil-sous-Bois. The next year he released his first picture L’Auberge Ensorcelee (1897), in which a man (Méliès himself) is frightened when his clothes disappear, his boots walk unaided and his furniture collapses.

Achieved with trick photography, this film was the beginning of a long string of Méliès special effects extravaganzas culminating La Voyage Dans La Lune aka A Trip To The Moon (1902). A huge turning point in the history of cinema, the narrative followed a group of ‘wise men’ (the word ‘scientist’ was still relatively new and unknown) who decide to fly to the moon, as the title suggests. Once there, they encounter Selenites, fairies and various other creatures before falling back to earth. The effects accomplished in the film consisted of trick photography, double-exposure and superimposed images. Not only was this film the real beginning of the use of special effects, but it is also responsible for introducing the traditional narrative structure. Before then, most films were just a few scenes without any real story.

For years, demand was high for the special effects films that Méliès created. While cinema was growing everywhere, Méliès films were much copied, yet no one was doing the kind of films that Melies could. The first animated film, Gertie The Dinosaur (1919), was created by Winsor McCay but it made no real impact other than being the first of it’s kind. Méliès became bankrupt in 1913, after refusing to evolve his style to suit new audience needs, yet his innovations remained in practice for decades. Cinema was moving away from the fantasies Melies was famous for, and dramas such as the Italian Quo Vadis? (1912) also marked the birth of the Historical Epic genre.

The first world war came and went and D.W. Griffiths released The Birth Of A Nation (1915). In the history of cinema this is an extremely important film due to its subject matter, length and it’s unnerving recreation of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. However, as far as special effects go, the only real innovation it marked was the introduction of colour. The images themselves were not in colour as such, but Griffiths washed entire scenes in different colours to represent mood.

The first world war came and went and D.W. Griffiths released The Birth Of A Nation (1915). In the history of cinema this is an extremely important film due to its subject matter, length and it’s unnerving recreation of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. However, as far as special effects go, the only real innovation it marked was the introduction of colour. The images themselves were not in colour as such, but Griffiths washed entire scenes in different colours to represent mood.

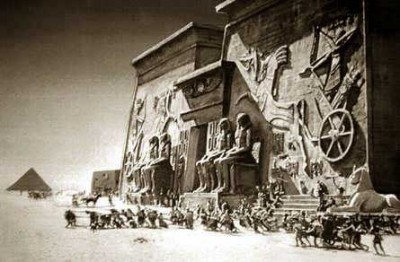

Cinema was coming along in leaps and bounds. The old school special effects were being perfected and used masterfully by many of the greats. As films became more grandiose, directors like Griffiths and Cecil B. De Mille made their mark. More and more money was being spent on film-making as the audience demand became extraordinary. De Mille was given large sums of money to build giant sets in favour of using special effects. Audiences wanted more realistic cinema. Films were now big business and the Hollywood system was firmly in place. However, progress in the field of special effects had hit a plateau.

Cinema was coming along in leaps and bounds. The old school special effects were being perfected and used masterfully by many of the greats. As films became more grandiose, directors like Griffiths and Cecil B. De Mille made their mark. More and more money was being spent on film-making as the audience demand became extraordinary. De Mille was given large sums of money to build giant sets in favour of using special effects. Audiences wanted more realistic cinema. Films were now big business and the Hollywood system was firmly in place. However, progress in the field of special effects had hit a plateau.

Speaking of plateaus, The Lost World (1925) introduced the world to the process of stop-motion animation and the remarkable work of artist Willis O’Brien. The Lost World is a direct ancestor of Jurassic Park (1993) and follows the story of Professor Challenger who sets out to prove that dinosaurs actually survived extinction and were living on an inaccessible plateau. It also features the famous Tyrannosaurus Rex/Triceratops fight that has since been referenced in countless films. For those of you too young to remember, stop-motion animation is a process whereby a metal skeleton encased in rubber (in this case a dinosaur) is created and then photographed one frame at a time with small adjustments made to the model between each frame to simulate movement.

1926 saw the introduction of rear screen projection in Buster Keaton‘s The General (1926). Rear screen projection is mainly used to show the outside world moving fast while the actor sits in a motionless vehicle. This special effect requires a pre-recorded background plate to be projected onto a screen and then filmed again with the actor performing in front of it.

1926 saw the introduction of rear screen projection in Buster Keaton‘s The General (1926). Rear screen projection is mainly used to show the outside world moving fast while the actor sits in a motionless vehicle. This special effect requires a pre-recorded background plate to be projected onto a screen and then filmed again with the actor performing in front of it.

Just as filmmakers were beginning to learn how to manipulate and move the camera, The Jazz Singer (1927) was released, marking the introduction of sound in cinema (also known as ‘talkies’) and movies became static again in order to satisfy the requirements of sound recording.

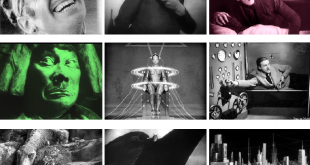

While this was a huge event, a far more important film was released that marked a leap forward in special effects. In Germany the very same year, Fritz Lang released Metropolis (1927) which was re-mastered again recently with a new soundtrack by Australian Benjamin Speed. This was a remarkable achievement and created effects such as the metamorphosis transition (from robot to woman) and various new camera tricks. More importantly, it paved the way for almost every science fiction film to follow.

James Whale‘s adaptation of Frankenstein (1931) is probably the first American film to use the glass matte painting effect. A glass matte involves an artist painting a realistic background onto a sheet of glass, leaving a space blank where the action will take place. When re-photographed it can look flawless, depending on the talents involved. Whale’s primitive use of the matte in Frankenstein was later perfected and taken to new levels in Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977).

James Whale‘s adaptation of Frankenstein (1931) is probably the first American film to use the glass matte painting effect. A glass matte involves an artist painting a realistic background onto a sheet of glass, leaving a space blank where the action will take place. When re-photographed it can look flawless, depending on the talents involved. Whale’s primitive use of the matte in Frankenstein was later perfected and taken to new levels in Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977).

King Kong (1933) re-introduced the world to the stop-motion work of Willis O’Brien, regarded by many as the greatest pre-digital special effects expert. In the climax of King Kong he used rear screen projection, models on wires and stop-motion animation to create the famous scene of the giant ape swatting at circling biplanes while atop the Empire State Building. The background was rear screen projection footage of real planes and the actual New York skyline. Placed in front of this was the model of the peak of the Empire State Building and the King Kong figure. In the foreground were biplanes on wires. Using stop-motion photography, O’Brien animated the entire shot, flawlessly blending the separate elements, the work involved being far more complex than I have room for here. O’Brien’s later films include the rushed Son Of Kong (1933), The Last Days Of Pompeii (1935), Mighty Joe Young (1949), Animal World (1955), The Black Scorpion (1957), The Giant Behemoth (1958) and finally the climax of It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963), but King Kong is still regarded as the crowning achievement of his career.

The thirties was a rich period in film history, full of great scripts and wonderful actors to perform them. The films of this era were groundbreaking, not in the type of effects used but more in the way they were used. The established processes were constantly being perfected and refined. The move toward realism had been slowed and the world of monsters was on the downturn. Subject matter had also diversified. While dramas were still very popular, the romance, gangster, western and epic genres were also being explored with effects being adapted to suit. This was a time when most of the physical effects like weather, fire, explosions, breakaway props and candied glass were being introduced. But there is one film innovation that must be mentioned: Technicolor.

The thirties was a rich period in film history, full of great scripts and wonderful actors to perform them. The films of this era were groundbreaking, not in the type of effects used but more in the way they were used. The established processes were constantly being perfected and refined. The move toward realism had been slowed and the world of monsters was on the downturn. Subject matter had also diversified. While dramas were still very popular, the romance, gangster, western and epic genres were also being explored with effects being adapted to suit. This was a time when most of the physical effects like weather, fire, explosions, breakaway props and candied glass were being introduced. But there is one film innovation that must be mentioned: Technicolor.

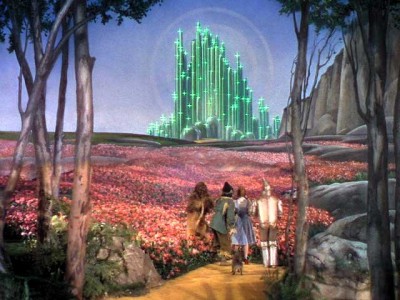

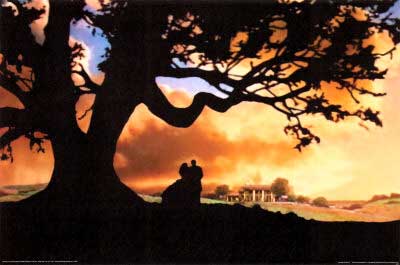

As Judy Garland stepped out of the farmhouse in The Wizard Of Oz (1939), audiences were bombarded with Technicolor. Deliberately garish and over-the-top, the colour was used as an effect in its own right. The first portion of the movie was filmed in a sepia tone to represent reality. Once Dorothy fell into Oz, Technicolor was used to show her dream world. Released the same year, Gone With The Wind (1939) used the unique properties of Technicolor to simulate the intense flames of the Atlanta inferno and the incredible beauty of its famous purple sunset.

As Judy Garland stepped out of the farmhouse in The Wizard Of Oz (1939), audiences were bombarded with Technicolor. Deliberately garish and over-the-top, the colour was used as an effect in its own right. The first portion of the movie was filmed in a sepia tone to represent reality. Once Dorothy fell into Oz, Technicolor was used to show her dream world. Released the same year, Gone With The Wind (1939) used the unique properties of Technicolor to simulate the intense flames of the Atlanta inferno and the incredible beauty of its famous purple sunset.

The period between 1893 and 1939 was an explosive time for cinema. In less than half a century the medium moved from Fred Ott’s Sneeze to Gone With The Wind.

The period between 1893 and 1939 was an explosive time for cinema. In less than half a century the medium moved from Fred Ott’s Sneeze to Gone With The Wind.

Even more remarkable is what was to come, as film audiences demanded more realism in their action and violence, coming to a crescendo in the late sixties and seventies with the graphic gore of Herschell Gordon Lewis and Tom Savini, not to mention the amazing prosthetics of Dick Smith, Rick Baker and Rob Bottin. But that’s another story for another time. So please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Hey, wonderful blog you have here! Keep up the excellent work

Hello, good evening and welcome! I can’t thank you enough for simply reading! All I ask you is, keep coming back! Toodles!