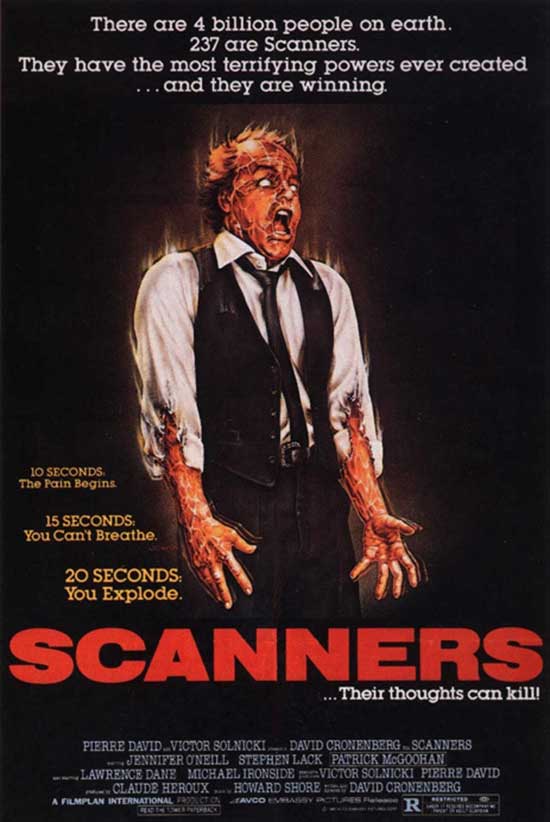

“Scanners” have special powers: they possess incredible telepathic abilities. Dangerous abilities. The ConSec security company wants to harness their powers for profit. Scanners, however, are difficult to control, and, when so inclined, they can invade the mind and literally cause heads to explode.

Can scientists convince “good” scanners to defeat deadly rogue scanners intent on domination? Or will evil corporatists get their way and control scanners for their purposes? Those questions come together to form the narrative plot. Viewers looking beyond the defined narrative can ask why artwork appears as a recurring motif, both overt and subtextual.

A Mind-Altering 1980’s Sci-Fi/Horror Classic

David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981) debuted when horror movies outside of the slasher subgenre seemed like anomalies. Equally parts cerebral and visceral, Scanners combined horror, science-fiction, and espionage genres to create a thrilling potboiler. The original promotional material for Scanners drove the film to box office success. Cronenberg’s film delivered three times the box office of the heavily hyped and excellent My Bloody Valentine (1981), a fellow Canadian horror import.

Perhaps Scanners did land at the right time. The film’s TV spots didn’t push the thought-provoking nature of the offbeat film. The spots promoted violence. While nowhere near as prurient as dozens of other horror films, Scanners‘ promotional material promised audiences would see violent deaths as telepathic “scanners” ripped their victims apart, body and mind.

The overt nature of the “mind-blowing” deaths hooked jaded audiences while providing them something much different than then-contemporary run-of-the-mill maniac-with-a-knife fare. Also driving the experience were Cronenberg’s themes, many of which were subtle. The presence of artwork and artistry as motifs hang in the background and add subtext to the action. They also draw correlations between scanners and the somewhat cliched notion of the tortured artist. The boundaries between the two do narrow in Scanners.

Director Ralph Bakshi employed the brilliant motif of pinball playing in the nihilistic masterpiece Heavy Traffic (1973). The recurring pinball images made no direct sense concerning the animated film’s plot, but they led astute audience members to think about “why” pinball machines and pinball playing recurred. Unanswerable, open-ended questions allow serious viewers to revisit cinematic works to explore possible thematic connections. With Scanners, “art” and “artists” hang in the background like portraits on the wall. Why does artwork seemingly reoccur in the film?

Perhaps the tortured existence of a minor character presents an answer.

The Sad and Lonely Life and Death of Benjamin Pierce

The formerly homeless Cameron Vale has a new purpose in life: track down fellow scanner Darryl Revok. Revok, now a murderous renegade, has launched a revolution against the exploitive ConSec security firm and, soon, all society. The only lead to Revok’s whereabouts is another scanner named Benjamin Pierce, a reclusive artist.

Pierce remains reclusive due to his poor mental state. While popular in the market, Pierce’s artwork has a grotesque quality that hints at a troubled, depressed creator. Who would want to interact with such a downbeat person? Art fans walk the tightrope of embracing Pierce’s art while ignoring his existence. That’s fine for Pierce. He wants nothing to do with them, either.

Pierce refuses to meet with buyers or fans. Gallery owners and art critics and fans see him as “yet another strange and tortured” artist. Whatever impressions drive their opinions of Pierce’s self-loathing isn’t correct. They don’t know he hates himself because he is different from them. He’s a scanner, a telekinetic freak of nature and science.

The parallels between scanning and creating art and the scanner and the artist, cross in several ways. Not all of them are positive. The tortured scanner is also a tortured artist. Scanners, due to their telekinetic powers, or different from people lacking those powers. For some, like Revok, the effect becomes akin to megalomaniacal delusions of conquest. For others, like the reluctant hero Vale and the tortured artist Pierce, the weight of being a scanner affects their mind. Again, there is an irony here as scanners manipulate the minds of others. For Vale, his mind cracks under the pressure of his powers. The mental decline leads to his former homelessness.

Pierce withdraws into his secluded home, and, while not homeless, he maintains no connection to society. Pierce understands he can never be part of human society, so he withdraws into isolation and cancels all interactions with others. Slowly descending into a self-imposed madness, he allows his trouble thoughts to manifest into disturbing artwork.

There exists a metaphorical aspect to this. Pierce finds himself outside of society, which is not atypical for the tortured artist. Many in the proverbial real world possess incredible artistic talents and none of the science-fiction-oriented telekinetic abilities of the scanners. Yet, they live somewhat similar lives of strange isolation because they cannot connect socially with others in traditional society.

Such is the pain of being different. And “mental noise” often reminds “the different” of their plight.

Voices in the Head

“Voices in the head” have to find a way out. For the scanners, the telepathic origins of reading minds cause them to suffer a mental overload. Hearing other people’s thoughts jumbled in the scanners’ heads leads to psychological breakdowns, as evidenced by Vale becoming homeless. For Revok, the psychic noise originally caused him to commit acts of self-harm. Through a flashback depicted via projected film, the audience learns he suffered a mental collapse at age 22 and drilled a hole in his head to “let the voices out.”

Revok’s acting out would eventually change. He moves from self-harm to homicidal tendencies as he launches an insane and murderous crusade to topple humanity with an army of scanners.

Regardless of the two diverse focuses of harm, similar parallels to the tortured artist emerge.

For Pierce, the “lost highway” scanner, the internal conflict translates into a desire to create outrageous sculptures. Like so many other artists, he allows the emotional noise inside the mind to morph into works of art. His artistry does not maintain modernist or realism, as he leans towards the more esoteric expressionist realm. Expressionist and abstract art focus more on the emotional than the intellectual. And Pierce’s work appears emotionally off-putting. While popular among a segment of consumers, the artwork comes off as grotesque, which keeps Pierce out of polite society. No matter. Pierce wants nothing to do with society. He sees himself as an outcast.

Consider Pierce atypical to the other scanners who embrace science and realism. Think of the value of ConSec’s computer system to the renegade Revok. The computers’ databanks of known scanners could provide a treasure of renegades in which to build an army.

Pierce represents his kind of renegade scanner. He could care less about Revok’s goals, nor does he embrace the “science side” of scanning. Instead, he escapes into isolation and a make-believe world of making artwork. Again, he can’t fit into society, so he uses his talents to remain on its fringes. However, the artwork is the manifestation of the problem: Pierce cannot reconcile his being a scanner? “Something” serves as the root torture for the tortured artist. For Pierce, scanning powers create the voices in his head. For others, “X, Y, and Z” may contribute to anxiety, depression, and paranoia. Regardless of the reason for the torture, the artist is tortured. Many live like Pierce, even though they have “traditional” psychiatric issues and not telepathic powers.

Art Therapy and Art-Inspired Institutionalization

Pierce’s psychological issues, like Revok’s and Vale’s, go back many years. His scanner-induced psychosis started during childhood and led him to confinement in a mental hospital after attempting to kill his entire family. His therapy included “rehabilitation through art.”

The bizarre artwork on display at the gallery reflects his terrifying institutionalization. Monstrous doctors hold a patient down while injecting him with “therapeutic drugs.” The “therapeutic violence” occurs while another doctor appears to touch the head of the patient lovingly. While the faces of the doctors mimic cartoonish monsters, everything else in the sculpture is frightening, plausibly real. Pierce’s expressionism is nothing of the sort. The sculptures are neo-modernism. Remove “scanning” and replace the power with a legitimate psychiatric disability. Were there numerous real-life patients of mental institutions who suffered similar abuses to that of Pierce? Of course, as untold numbers of cases document harrowing experiences.

Another sculpture reveals an equally revolting image.

A handcrafted wall of screaming faces looks down at a man whose face is frozen in a horrible, dead expression. Red “veins” connect the patient’s head to the screaming faces on the wall above. Are those the “voice” in Pierce’s head. Likely, they are. The voices are not merely voices, though. The voices come from real people who influenced his mental breakdown.

The brief scene revealing this artwork does carry a great deal of thematic resonance. Examine the exchange where the art gallery’s owner talks of Pierce’s “power” to an inquisitive Vale. The pun here is obvious: artistic power corresponds to the scanner power. For Pierce, artistic power, scanning power, and psychological disempowerment all form a singular triangle.

Although the sanitarium days are long behind him, Pierce remains institutionalized in his remote cabin-turned-art-studio, Pierce works on creating various garish works, including a masterpiece: a giant, King Kong-sized, human head.

Pierce reveals to Vale he stops the voices in his head through his art, his art “keeps him sane” and points to his head upon saying so. The obsessive giant head sculpture shows Pierce’s obsessions. Art creates an escape, as it provides a safe haven for Pierce to hide from the world. While there is therapy in creating art, there is an isolation that goes along with it. Unfortunately, reality tends to impose itself on those wishing to escape it. Pierce might not be interested in the scanner revolution, but the revolution has an interest in him. Revok’s bounty hunters eventually track him down, and their actions set several events in motion that lead to Vale and Revok’s final confrontation.

The Sculpture of the Mind

A somewhat ironic aspect of the art motif makes a brief and not-entirely-subtle appearance in the final violent confrontation between the antagonist and protagonist scanners. After a tense exchange, Vale grabs a small sculpture off a desk and cracks it across the skull of Revok to set up the conclusion. Hitting Revok with the sculpture does next to nothing other than provoking a violent reaction. The ensuing battle between the two involves telekinetic energy that tears their physical bodies apart.

Without giving too much away and spoiling the ending, the final confrontation focuses on the art’s scientific roots that unfold with the tale of the scanners. The use of the sculpture shows that art, created by a combination of hand in mind, isn’t always an abstract entity. Art may serve as a tool, a mentally therapeutic one, or a physical tool, in this case, a weapon. Art becomes a blunt weapon, about a primal a weapon one could use.

Art does have its practicality. Unfortunately, it has its limits. As a weapon, it works little against the evil scanner. As a therapeutic escape, it can only do so much to solve the evils scanning inflicts on the scanner’s mind.

But it still does something. A sharp mind could turn that into a positive.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews