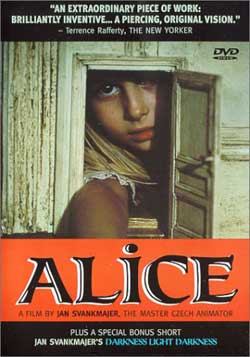

A surrealistic revision of Alice in Wonderland.

REVIEW:

“You must…close your eyes…otherwise…you won’t see anything.”

Czech filmmaker, Jan Svankmajer, has led an illustrious career with his surrealist films, many of which are told from the perspective of a child. He has influenced filmmakers young and old, from Terry Gilliam to the Brothers Quay with a celebrated catalog of feature and short films such as Dimensions of Dialogue, Faust, Little Orik, and Conspirators of Pleasure. Something From Alice (the English translation of the original title, Neco z Aleky), released in 1988, was Svankmajer’s feature film debut and is, less an adaptation than, a deconstruction of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Svankmajer emphasizes throughout the film that Alice is the storyteller (by brusquely cutting to Alice’s mouth which provides fragmented exposition). There is a theatrical hyper-realism to the film that is brooding yet darkly humourous.

We are introduced to Alice (Kristyna Kohoutova) sitting on the cluttered floor in her bedroom mindlessly tossing rocks into various containers filled with water dripping from holes in the ceiling. Encased in a glass case is a taxidermically-stuffed white rabbit which becomes animated and escapes his glass prison. Alice, out of curiosity, out of boredom, follows him into a chest of drawers, to a cavern, and beyond. What Svankmajer chooses to include or exclude (the Cheshire Cat makes no appearance) in the film is a result of purely interpreting the text without the traditional accompaniment of illustrations (as Disney and other adaptations have done) – the approximation and volatility of a child’s boundless imagination is conveyed conceptually in the inherent structure of the film.

Svankmajer’s world is populated by rust and decay, rejects and grime. A world in a state of collapse, stark and uncompromising, stretches of wasteland, peeling wallpaper, gigantic toys, and dark industrial elevators – a fever dream as primal as it is bizarre. Painted backdrops, puppetry, stop-motion, and live-action are only a few of the techniques employed to comprise Alice’s fantasy. As the opening lines of the film declare (“Now you will see a film…made for children…perhaps”), it is more about childhood than a work geared toward children (though it isn’t necessarily inappropriate either).

The capricious nature of a child’s early progress is accurate in the undefined transitions from enchantment to concern, curiosity and disillusionment. Alice continually shifts from one awkward state to another – the predominant trial of childhood. The film has many recurring themes (the Mad Hatter sequence is both exasperating and jarringly hypnotic), transient environments, compulsive symbolism, and lucid nonsense. The typical Victorian presentation characteristic of most adaptations is starkly contrasted here with the grotesque and barren, and restrained the use of the book’s dazzling wordplay. It is a film which affects the unconscious, allowing the viewer to form a subjective context through the progression of dream logic. There’s no attempt to clarify odd visual juxtapositions or exaggeration in the commonplace only the accompaniment of hyperbolic sound effects to further disconnect the audience from reality.

Svankmajer regarded Carroll’s book as one of the most important works in literature and it was this love which encouraged his transition from twenty years of shorts to feature films, but his adaptation took care to emphasize the preteen experience; those wondrous moments of early life when the world is beheld with mystery and astonishment, bewilderment and terror. The fragmentary, uncertain but familiar, brooding atmosphere of Svankmajer’s vision is, while not the most literal, the most representative adaptation of Carroll’s work in cinematic history.

Rating: A+

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews