SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Adélaïde, Belle, Félicie and Ludovic are young adult siblings who once lived in grandeur until their father’s merchant ships were lost at sea. The family is now near ruin, but Adélaïde and Félicie nonetheless still squander away the family money on themselves and keeping beautiful, whereas Belle slaves around the house, doting on her father. Ludovic detests his two spoiled sisters, but is protective of Belle, especially with his friend Avenant, a handsome scoundrel who wants to marry Belle. Crossing the forest one dark and stormy evening, the father gets lost and takes refuge in a fantastical castle. Upon leaving, he steals a blossom off a rose bush, which Belle requested. The castle’s resident, an angry beast, sentences him to one of two options for the theft of the rose: his own death, or that of one of his daughters. As she feels she is the cause of her father’s predicament (despite her sisters asking for far more lavish gifts), Belle sacrifices herself to the beast. Upon arriving at the castle, Belle finds that the beast, whose grotesqueness she cannot deny, does not want to kill her, but wants to marry her and lavish her with riches. He does not force her, but he will ask her every night to marry him, these times the only ones when he will appear to her. She vows never to say yes. As Belle resigns herself to her mortal fate and looks deeper into the beast – whose grotesque exterior masks a kind but tortured soul – will her thoughts change? Meanwhile, Belle’s family, who learn of her situation, have their own thoughts of what to do, some working toward what they believe is Belle’s best welfare, and others working toward their own benefit.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

It may be surprising that, in Germany, the war years bred an appetite for light fantasy, just as they did in Hollywood. The twenty-fifth anniversary of the famous Ufa Studios was due in 1943, and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1943) was a big-budget spectacular designed to celebrate the event. Around the same year, there were problems making films in France while under German occupation and international critics, when these works were exported after the war, saw French cinema of the period as dipping into the world of fantasy, films without hope for the future. L’Eternal Retour (1943) was directed by Jean Delannoy from a script by playwright and artist Jean Cocteau, a retelling in modern dress of the legend of Tristan And Isolde. This tale of doomed love is enlivened by delicate fantastic images throughout: The black scarf fluttering from the boat; the streaming blonde hair of the lovers; etc.

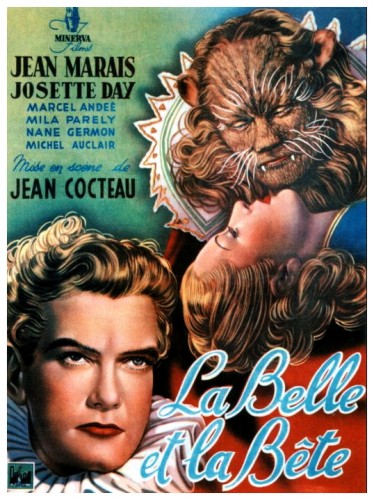

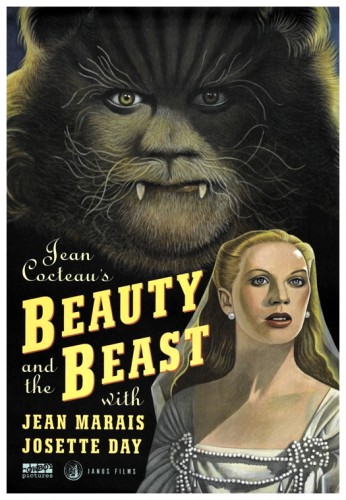

Cocteau remains almost unique in cinema – poet, novelist, playwright, surrealist, memoirist, opium enthusiast and collaborator with almost everyone from Pablo Picasso to Erik Satie. He only made a handful of films, all influential, and his aristocratic bearing, artistic aspiration and sense of stylistic exactitude are comparable only with that of Erich Von Stroheim. L’Eternal Retour now seems a little like a five-finger exercise, made to prepare Cocteau for his own two great fantasy films of the post-war years: Beauty And The Beast (1946) and Orphee (1950). Both films were quite successful, but they make no concessions to commercialism. Both are very consciously works of art, in fact Beauty And The Beast begins exactly like a Flemish painting though it soon moves into the more sinister world of fairy-tales.

Cocteau remains almost unique in cinema – poet, novelist, playwright, surrealist, memoirist, opium enthusiast and collaborator with almost everyone from Pablo Picasso to Erik Satie. He only made a handful of films, all influential, and his aristocratic bearing, artistic aspiration and sense of stylistic exactitude are comparable only with that of Erich Von Stroheim. L’Eternal Retour now seems a little like a five-finger exercise, made to prepare Cocteau for his own two great fantasy films of the post-war years: Beauty And The Beast (1946) and Orphee (1950). Both films were quite successful, but they make no concessions to commercialism. Both are very consciously works of art, in fact Beauty And The Beast begins exactly like a Flemish painting though it soon moves into the more sinister world of fairy-tales.

A young village girl named Belle (Josette Day) offers herself up to the local seigneur in lieu of her father’s life, who has innocently stolen a rose from the chateau garden. The seigneur (Jean Marais) is a mysterious person who is rumoured to be extraordinarily ugly, except in this version he isn’t – he’s a p**sycat. She has already been approached by a local squire named Avenant (Jean Marais) but, transported to the magical chateau, she slowly realises that Avenant and the beastly seigneur might be one-and-the-same. The castle is a strange haunted place, with candelabra held by living arms projecting into the dark corridors, and there are living statues too. The Beast admits his love for Beauty and tests her by allowing her to visit her family, stating that if she does not return, he will certainly die of grief.

A young village girl named Belle (Josette Day) offers herself up to the local seigneur in lieu of her father’s life, who has innocently stolen a rose from the chateau garden. The seigneur (Jean Marais) is a mysterious person who is rumoured to be extraordinarily ugly, except in this version he isn’t – he’s a p**sycat. She has already been approached by a local squire named Avenant (Jean Marais) but, transported to the magical chateau, she slowly realises that Avenant and the beastly seigneur might be one-and-the-same. The castle is a strange haunted place, with candelabra held by living arms projecting into the dark corridors, and there are living statues too. The Beast admits his love for Beauty and tests her by allowing her to visit her family, stating that if she does not return, he will certainly die of grief.

The Beast is not quite the vision of ugliness that the old story insists on, his leonine head is almost majestic and he has a gentleness about him that makes his final transformation to fairy-tale Prince Ardent perhaps less surprising than it might have been. At the end, in a superbly over-the-top sequence of high romance, he flies through the sky with Beauty to some paradise for sanctified lovers. As an exercise in romantic symbolism, the film is not especially erotic – Cocteau’s vision of women tends to be idealised, decorative and other-worldly. He himself found fulfillment in other men, and Avenant/Beast/Ardent is played by his long-time lover Jean Marais, but it makes up for this in consistency of its allegorical texture, somewhat stylised, sometimes calming, sometimes macabre, but always alive and inventive.

The Beast is not quite the vision of ugliness that the old story insists on, his leonine head is almost majestic and he has a gentleness about him that makes his final transformation to fairy-tale Prince Ardent perhaps less surprising than it might have been. At the end, in a superbly over-the-top sequence of high romance, he flies through the sky with Beauty to some paradise for sanctified lovers. As an exercise in romantic symbolism, the film is not especially erotic – Cocteau’s vision of women tends to be idealised, decorative and other-worldly. He himself found fulfillment in other men, and Avenant/Beast/Ardent is played by his long-time lover Jean Marais, but it makes up for this in consistency of its allegorical texture, somewhat stylised, sometimes calming, sometimes macabre, but always alive and inventive.

This is perhaps cinema’s most poetic work, full of hauntingly beautiful dreamlike imagery, most memorable are the merchant’s terrifying visit to the Beast’s dark forbidding castle, in which statues move and unattached arms extend from the walls holding candelabras, and Beauty’s arrival at the castle, in which she seems to float as she walks trance-like through the various rooms and hallways, complete with billowing curtains. Cocteau said he was exploring “The reality of the unreal” and only though his surreal imagery did he believe he could convey the precise emotions, feelings and atmosphere that he believed represented absolute truth. For instance, when Beauty’s wicked sister looks into the Beast’s mirror and a monkey is reflected back at her, the monkey’s image is ‘unreal’ but it reveals the truth, the reality about her.

This is perhaps cinema’s most poetic work, full of hauntingly beautiful dreamlike imagery, most memorable are the merchant’s terrifying visit to the Beast’s dark forbidding castle, in which statues move and unattached arms extend from the walls holding candelabras, and Beauty’s arrival at the castle, in which she seems to float as she walks trance-like through the various rooms and hallways, complete with billowing curtains. Cocteau said he was exploring “The reality of the unreal” and only though his surreal imagery did he believe he could convey the precise emotions, feelings and atmosphere that he believed represented absolute truth. For instance, when Beauty’s wicked sister looks into the Beast’s mirror and a monkey is reflected back at her, the monkey’s image is ‘unreal’ but it reveals the truth, the reality about her.

Josette Day is perfectly cast as one of literature’s great heroines – innocent, honest, loyal, exquisite, virtuous and strong of character. Less impressive is Jean Marais who plays three characters – the foolishly obnoxious rapscallion Avenant whom Beauty loves, the self-pitying but elegant-looking Beast and, worst of all, the rather effeminate Prince Ardent that the Beast becomes at the end. The Beast’s transformation from a true king into a prissy prince is the worst scene in the film and, also considering how the pleased Beauty suddenly becomes uncharacteristically flirtatious, almost ruins everything that went before it.

Josette Day is perfectly cast as one of literature’s great heroines – innocent, honest, loyal, exquisite, virtuous and strong of character. Less impressive is Jean Marais who plays three characters – the foolishly obnoxious rapscallion Avenant whom Beauty loves, the self-pitying but elegant-looking Beast and, worst of all, the rather effeminate Prince Ardent that the Beast becomes at the end. The Beast’s transformation from a true king into a prissy prince is the worst scene in the film and, also considering how the pleased Beauty suddenly becomes uncharacteristically flirtatious, almost ruins everything that went before it.

Much of the film’s charm is that it is presented so simply, without self-indulgence or pretense. While the film can be seen as a Freudian tale (Beauty has a strong attachment to her father, the Beast and Avenant represent two parts of one split personality, etc.), in my humble yet always accurate opinion, I prefer to think of it as a merely innocent and literal adaptation of the children’s story written by Madame Le Prince De Beaumont. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because an old carny told me that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the entire world will come to a nasty end. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but he was just so certain, I feel we’d best not take the risk. So enjoy your week, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

Much of the film’s charm is that it is presented so simply, without self-indulgence or pretense. While the film can be seen as a Freudian tale (Beauty has a strong attachment to her father, the Beast and Avenant represent two parts of one split personality, etc.), in my humble yet always accurate opinion, I prefer to think of it as a merely innocent and literal adaptation of the children’s story written by Madame Le Prince De Beaumont. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because an old carny told me that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the entire world will come to a nasty end. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but he was just so certain, I feel we’d best not take the risk. So enjoy your week, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews