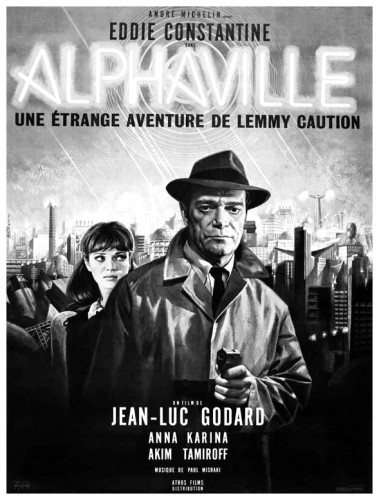

“Lemmy Caution, an American private-eye, arrives in Alphaville, a futuristic city on another planet. His very American character is at odds with the city’s ruler, an evil scientist named Von Braun, who has outlawed love and self-expression.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

One cannot speak of the European ‘New Wave’ movement of the sixties without mentioning French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who often criticised the industry’s tradition of emphasising craft over innovation, established directors over new directors, and past works over experimentation. To challenge this tradition, he started making his own films, many of which challenged the conventions of traditional Hollywood as well as French cinema. Godard was one of the most radical filmmakers of the sixties and seventies, and most of his movies express his political views as well as his knowledge of film history. Breathless (1960) starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg distinctly expresses the New Wave, incorporating elements of popular culture, employing innovative techniques such as jump-cuts, character asides and breaking established rules of photography and editing.

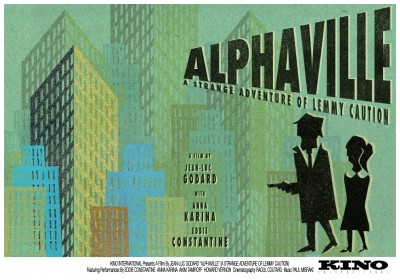

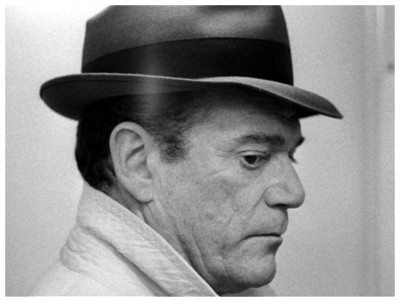

Godard was more interested in redefining film structure and style than actually being understood by the public. His movies were more often about the presentation of a story than anything else. Whether or not Godard’s Alphaville: A Strange Adventure Of Lemmy Caution (1965) properly qualifies as science fiction is a matter for debate. It concerns intergalactic secret agent Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine), who is sent to the planet Alphaville to deal with an evil computer used by tyrants to control and suppress the citizens. Godard has transformed the pulp elements of the original story into an ambiguous allegory of contemporary technology-dominated society. Alphaville itself is a thinly disguised modern-day Paris, and Lemmy doesn’t use a spaceship to get there, but simply drives his Ford through ‘intersidereal space’ which is essentially an ordinary highway.

Godard was more interested in redefining film structure and style than actually being understood by the public. His movies were more often about the presentation of a story than anything else. Whether or not Godard’s Alphaville: A Strange Adventure Of Lemmy Caution (1965) properly qualifies as science fiction is a matter for debate. It concerns intergalactic secret agent Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine), who is sent to the planet Alphaville to deal with an evil computer used by tyrants to control and suppress the citizens. Godard has transformed the pulp elements of the original story into an ambiguous allegory of contemporary technology-dominated society. Alphaville itself is a thinly disguised modern-day Paris, and Lemmy doesn’t use a spaceship to get there, but simply drives his Ford through ‘intersidereal space’ which is essentially an ordinary highway.

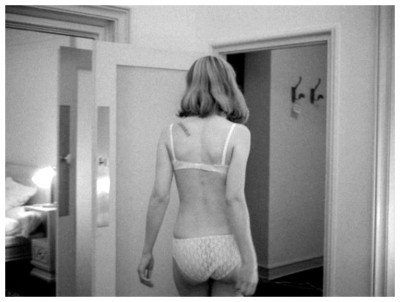

Posing as a newspaper reporter, hard-boiled agent Lemmy is assigned to find a fellow agent named Dickson (Akim Tamiroff) and assassinate the nefarious scientist Professor Leonard Nosferatu (Howard Vernon), creator of the powerful and loquacious Alpha 60 computer that dominates the planet. Lemmy gets the lowdown on this robotised society where technology has replaced humanity; where all those who don’t think logically are either repressed or murdered; where women have numbers tattooed on their backs and function as prostitutes or seducers; where words such as ‘conscience’ and ‘love’ do not exist in its bible-dictionary. It’s Lemmy’s job to destroy the computer which will, in turn, cause the destruction of Alphaville.

Posing as a newspaper reporter, hard-boiled agent Lemmy is assigned to find a fellow agent named Dickson (Akim Tamiroff) and assassinate the nefarious scientist Professor Leonard Nosferatu (Howard Vernon), creator of the powerful and loquacious Alpha 60 computer that dominates the planet. Lemmy gets the lowdown on this robotised society where technology has replaced humanity; where all those who don’t think logically are either repressed or murdered; where women have numbers tattooed on their backs and function as prostitutes or seducers; where words such as ‘conscience’ and ‘love’ do not exist in its bible-dictionary. It’s Lemmy’s job to destroy the computer which will, in turn, cause the destruction of Alphaville.

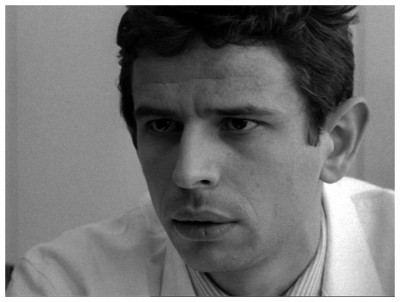

In the course of his mission he encounters Natacha Von Braun (Anna Karina), the evil professor’s beautiful daughter, with whom he falls in love. Indeed, it is love – and the ability to express it with words – that ultimately allows humans to escape from Alphaville and its fascist repression of sentiment and hope. Of course, by this time Godard had established himself as a director for whom the conflation of genres was not so much a stylistic device as a critical avenue for launching cultural and aesthetic inquiries into cinema itself. Consequently Alphaville’s plot provides the scaffolding around which Godard crafts a multi-layered and profoundly insightful work. For example, in addition to its action-packed narrative, Alphaville functions as an homage to many of cinema’s great auteurs, from F.W. Murnau and Jean Cocteau to Fritz Lang and Howard Hawks.

In the course of his mission he encounters Natacha Von Braun (Anna Karina), the evil professor’s beautiful daughter, with whom he falls in love. Indeed, it is love – and the ability to express it with words – that ultimately allows humans to escape from Alphaville and its fascist repression of sentiment and hope. Of course, by this time Godard had established himself as a director for whom the conflation of genres was not so much a stylistic device as a critical avenue for launching cultural and aesthetic inquiries into cinema itself. Consequently Alphaville’s plot provides the scaffolding around which Godard crafts a multi-layered and profoundly insightful work. For example, in addition to its action-packed narrative, Alphaville functions as an homage to many of cinema’s great auteurs, from F.W. Murnau and Jean Cocteau to Fritz Lang and Howard Hawks.

Alphaville also serves as a platform for placing multiple discourses on the structure of time and the value of the human imagination into a dialogue designed to provide as many questions as potential answers. Furthermore, the film critiques the dehumanising potential of modernist architecture, as well as the political dangers of censorship. Though the city of Alphaville is described as a futuristic metropolis on another planet, the setting is unmistakably 1965 Paris. Acknowledging this strategy is essential to understanding the film’s embedded messages. Godard is a filmmaker concerned with the present-day, carefully loading his works with references to contemporary events and political concerns. In this sense Alphaville conforms to Ursula K. Le Guin‘s observation that, “Science fiction is not predictive, it is descriptive.”

Alphaville also serves as a platform for placing multiple discourses on the structure of time and the value of the human imagination into a dialogue designed to provide as many questions as potential answers. Furthermore, the film critiques the dehumanising potential of modernist architecture, as well as the political dangers of censorship. Though the city of Alphaville is described as a futuristic metropolis on another planet, the setting is unmistakably 1965 Paris. Acknowledging this strategy is essential to understanding the film’s embedded messages. Godard is a filmmaker concerned with the present-day, carefully loading his works with references to contemporary events and political concerns. In this sense Alphaville conforms to Ursula K. Le Guin‘s observation that, “Science fiction is not predictive, it is descriptive.”

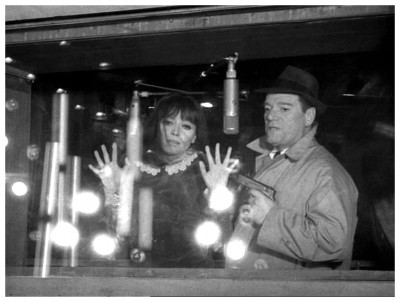

The political themes may not seem that novel by today’s standards, but Godard’s direction is consistently offbeat and fascinating. His use of flickering lights (like Lemmy’s flash camera), sounds (like the monstrous mechanical voice of the computer), ominous soundtrack music by Paul Misraki, choice settings and sudden unexpected actions by characters (Lemmy shoots first and asks questions later), all of which succeeds in making the viewer feel like they’re in another world with rhythms and hues different from our own. The movie also has the novel twist of having a two-fisted tough-guy teaching a sensual female the meaning of ‘love’. Alphaville contains a maze of allusions culled from a large variety of sources, including Hollywood B-grade films, comic books, thrillers, and even cartoons (at one point we meet two scientists named Doctor Heckle and Doctor Jeckyll) as well as traditional science fiction.

The political themes may not seem that novel by today’s standards, but Godard’s direction is consistently offbeat and fascinating. His use of flickering lights (like Lemmy’s flash camera), sounds (like the monstrous mechanical voice of the computer), ominous soundtrack music by Paul Misraki, choice settings and sudden unexpected actions by characters (Lemmy shoots first and asks questions later), all of which succeeds in making the viewer feel like they’re in another world with rhythms and hues different from our own. The movie also has the novel twist of having a two-fisted tough-guy teaching a sensual female the meaning of ‘love’. Alphaville contains a maze of allusions culled from a large variety of sources, including Hollywood B-grade films, comic books, thrillers, and even cartoons (at one point we meet two scientists named Doctor Heckle and Doctor Jeckyll) as well as traditional science fiction.

It may not be entirely successful, but Alphaville definitely has moments of brilliance, such as the inspired casting of B-movie actor Constantine as Lemmy, and the exceptional photography by Raoul Coutard. I’ll now make my fond farewells, but not before politely inviting you to please join me again next week when I fish-out more celluloid slop from the wheelie-bin behind Fox Studios and force-feed it to you without a spoon, all in the name of art for…Horror News. Toodles!

It may not be entirely successful, but Alphaville definitely has moments of brilliance, such as the inspired casting of B-movie actor Constantine as Lemmy, and the exceptional photography by Raoul Coutard. I’ll now make my fond farewells, but not before politely inviting you to please join me again next week when I fish-out more celluloid slop from the wheelie-bin behind Fox Studios and force-feed it to you without a spoon, all in the name of art for…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews