SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

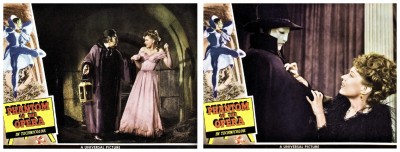

“Pit violinist Claudin hopelessly loves rising operatic soprano Christine Dubois (as do baritone Anatole and police inspector Raoul) and secretly aids her career. But Erique Claudin loses both his touch and his job, murders a rascally music publisher in a fit of madness, and has his face etched with acid. Soon, mysterious crimes plague the Paris Opera House, blamed on a legendary Phantom whom none can find in the mazes and catacombs. But both of Christine’s lovers have plans to ferret him out.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Erik, the man with a hideous skull-like face who lives in furtive seclusion beneath a Paris opera house, is in love with a beautiful singer. He masks his deformity and commits various murders in order to attain his ends, but nevertheless fails to get the girl. His story is told in Gaston Leroux‘s 1911 novel The Phantom Of The Opera, which was filmed in 1925 with Lon Chaney Senior in the leading role. Since then it has become a standard part of the cinema’s horror repertoire, with remakes appearing in 1943 starring Claude Rains and in 1962 with Herbert Lom. A later version entitled Phantom Of The Paradise (1974) had William Finley in an updated story with a rock-music setting directed by Brian DePalma with an award-winning soundtrack by Paul Williams. There was also a made-for-television movie in 1983 starring Maximillian Schell, and another notable performance came from Robert Englund in a 1986 version which played-up the horror elements of the story. Since then Leroux’s hoary old tale has been given a new lease on life as a stage musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber, which was adapted into a 2004 film directed by Joel Schumacher, and the stage musical itself was also captured on film for its 25th anniversary.

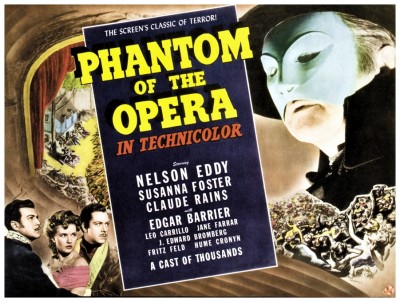

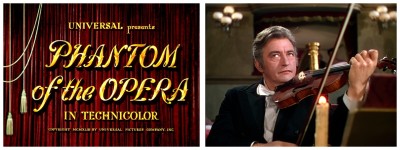

But I’ve gathered you here today to discuss the 1943 version starring Claude Rains, which attempts to bring a little more humanity into the romantic tale of a beauty and her beast. Following the successful release of The Wolf Man (1941), Universal Studios executives put their thinking caps on and came up with the idea of remaking one of their most successful silent films. Then they removed their thinking caps, stuck their thumbs up their arses and decided the remake should be a comedy starring Bud Abbott and Lou Costello as stagehands, Lon Chaney Junior as the Phantom with Jon Hall and Deanna Durbin as the romantic leads, to be directed by Henry Koster. Thankfully, wiser minds prevailed and, when a then-huge budget of $1,750,000 was allocated, Universal chose to take things seriously by utilising recent improvements in sound reproduction and Technicolor cinematography. Experienced director Arthur Lubin was hired, with popular singers Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster as the romantic leads, and Universal horror staple Claude Rains was given the pivotal role of the Phantom.

But I’ve gathered you here today to discuss the 1943 version starring Claude Rains, which attempts to bring a little more humanity into the romantic tale of a beauty and her beast. Following the successful release of The Wolf Man (1941), Universal Studios executives put their thinking caps on and came up with the idea of remaking one of their most successful silent films. Then they removed their thinking caps, stuck their thumbs up their arses and decided the remake should be a comedy starring Bud Abbott and Lou Costello as stagehands, Lon Chaney Junior as the Phantom with Jon Hall and Deanna Durbin as the romantic leads, to be directed by Henry Koster. Thankfully, wiser minds prevailed and, when a then-huge budget of $1,750,000 was allocated, Universal chose to take things seriously by utilising recent improvements in sound reproduction and Technicolor cinematography. Experienced director Arthur Lubin was hired, with popular singers Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster as the romantic leads, and Universal horror staple Claude Rains was given the pivotal role of the Phantom.

Despite the lavish production values, there’s several problems with this particular version, not least being the inexplicable reason for giving the Phantom the surname of Claudin. Leroux’s original Phantom is known simply as Erik, and is not so much a villain as a tragic anti-hero. He was born monstrously deformed, so we can forgive him because of the profound psychological damage he must have suffered throughout his life. He lives in the catacombs beneath the Opera House because he is too hideous to live anywhere else. The employees of the Opera House know him as the Phantom because he has been there for decades, using his great intelligence and his knowledge of the building’s internal layout to mythologise himself as something more than natural, protecting himself from the hatred of those not like him by playing upon their fear of him. He has loved Christine since she first appeared at the opera, and has spent years ingratiating himself by teaching her to out-sing any potential rival.

Despite the lavish production values, there’s several problems with this particular version, not least being the inexplicable reason for giving the Phantom the surname of Claudin. Leroux’s original Phantom is known simply as Erik, and is not so much a villain as a tragic anti-hero. He was born monstrously deformed, so we can forgive him because of the profound psychological damage he must have suffered throughout his life. He lives in the catacombs beneath the Opera House because he is too hideous to live anywhere else. The employees of the Opera House know him as the Phantom because he has been there for decades, using his great intelligence and his knowledge of the building’s internal layout to mythologise himself as something more than natural, protecting himself from the hatred of those not like him by playing upon their fear of him. He has loved Christine since she first appeared at the opera, and has spent years ingratiating himself by teaching her to out-sing any potential rival.

Claude Rains’ Phantom isn’t tragic – he’s just plain insane. In Leroux’s novel, we pity the Phantom’s hopeless love for Christine because it is truly and irredeemably hopeless, but Claudin’s love for Christine is only hopeless because he was too scared to ask her out even before his face was burned by acid. In fact, the original script reveals Claudin to be Christine’s father, who abandoned her in order to pursue a musical career. When this was excised from the final draft, it left Claudin’s obsession with Christine completely unexplained. Worst of all, Claudin’s short tenure as the Phantom makes it patently ridiculous that all of the stagehands know and fear him – it usually takes more than a couple of weeks to establish a legend.

Claude Rains’ Phantom isn’t tragic – he’s just plain insane. In Leroux’s novel, we pity the Phantom’s hopeless love for Christine because it is truly and irredeemably hopeless, but Claudin’s love for Christine is only hopeless because he was too scared to ask her out even before his face was burned by acid. In fact, the original script reveals Claudin to be Christine’s father, who abandoned her in order to pursue a musical career. When this was excised from the final draft, it left Claudin’s obsession with Christine completely unexplained. Worst of all, Claudin’s short tenure as the Phantom makes it patently ridiculous that all of the stagehands know and fear him – it usually takes more than a couple of weeks to establish a legend.

Unfortunately, the extravagant use of sets and costumes, and the overuse of operatic arias significantly dilutes the suspense quotient, and the comedic pairing of Nelson Eddy and Edgar Barrier doesn’t help. This retelling contains a lot more ‘Opera’ than ‘Phantom’ but that’s because the stars are soprano Susanna Foster and tenor Nelson Eddy. The war in Europe made it difficult to track down the rights to most operas, which is why all the operas performed in the film are copyright-free Public Domain pieces. Of the three ‘operas’ in the film only the first (Marta) is an actual opera by Friedrich von Flotow. The second (Amore et Gloire) was adapted from music originally written for piano by Frederic Chopin. The music of the third opera (Le Prince Masque De Caucasie) is actually from the finale of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky‘s Fourth Symphony. The filmmakers were able to slip in a reference to the opera Faust without actually using any of its music by having Christine appear in the Marguerite costume as she comes off stage.

Unfortunately, the extravagant use of sets and costumes, and the overuse of operatic arias significantly dilutes the suspense quotient, and the comedic pairing of Nelson Eddy and Edgar Barrier doesn’t help. This retelling contains a lot more ‘Opera’ than ‘Phantom’ but that’s because the stars are soprano Susanna Foster and tenor Nelson Eddy. The war in Europe made it difficult to track down the rights to most operas, which is why all the operas performed in the film are copyright-free Public Domain pieces. Of the three ‘operas’ in the film only the first (Marta) is an actual opera by Friedrich von Flotow. The second (Amore et Gloire) was adapted from music originally written for piano by Frederic Chopin. The music of the third opera (Le Prince Masque De Caucasie) is actually from the finale of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky‘s Fourth Symphony. The filmmakers were able to slip in a reference to the opera Faust without actually using any of its music by having Christine appear in the Marguerite costume as she comes off stage.

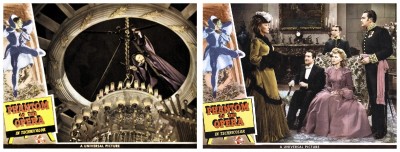

Speaking of which, I’d like to pay homage to the courage of Parisian opera lovers. I’m in absolute awe of the way they flock to a performance of Faust, just two nights after so many of their fellow opera buffs were squished beneath an enormous chandelier, now restored to its place above their heads. Maybe they should try something safer, like running with the bulls in Pamploma. The auditorium and stage of the Paris Opera House is the same set built for the 1925 version and has been used for countless other productions ever since. Inside Universal Sound Stage #28, the opera house set continues to stand where it was filmed almost a century ago, making it the oldest standing interior film set in the world. Though it remains impressive, time has taken its toll and it is very rarely used. Urban legends claim the set remains because when workers have attempted to take it down in the past there have been fatal accidents, said to be caused by the ghost of Lon Chaney Senior.

Speaking of which, I’d like to pay homage to the courage of Parisian opera lovers. I’m in absolute awe of the way they flock to a performance of Faust, just two nights after so many of their fellow opera buffs were squished beneath an enormous chandelier, now restored to its place above their heads. Maybe they should try something safer, like running with the bulls in Pamploma. The auditorium and stage of the Paris Opera House is the same set built for the 1925 version and has been used for countless other productions ever since. Inside Universal Sound Stage #28, the opera house set continues to stand where it was filmed almost a century ago, making it the oldest standing interior film set in the world. Though it remains impressive, time has taken its toll and it is very rarely used. Urban legends claim the set remains because when workers have attempted to take it down in the past there have been fatal accidents, said to be caused by the ghost of Lon Chaney Senior.

Following the success of Phantom Of The Opera, Universal announced that a sequel would be produced. There is, after all, a hint that Erique Claudin survived the cave-in during the finale – in the final shot of the mask and violin, there is a sound of moving rocks. Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster were ready to return, along with Claude Rains as the Phantom. Unfortunately, the idea of a sequel was later cancelled due to story troubles and problems arose concerning the availability of Rains, who was at the peak of his terribly busy career at the time. The Climax (1944) was released the year after Phantom Of The Opera, but was not really a continuation and featured completely new characters. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll simply request your presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of Hollywoodland, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Following the success of Phantom Of The Opera, Universal announced that a sequel would be produced. There is, after all, a hint that Erique Claudin survived the cave-in during the finale – in the final shot of the mask and violin, there is a sound of moving rocks. Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster were ready to return, along with Claude Rains as the Phantom. Unfortunately, the idea of a sequel was later cancelled due to story troubles and problems arose concerning the availability of Rains, who was at the peak of his terribly busy career at the time. The Climax (1944) was released the year after Phantom Of The Opera, but was not really a continuation and featured completely new characters. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll simply request your presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of Hollywoodland, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews