How things have changed. In the forties, for instance, one would find it difficult to name twenty good genre films of the decade but, since the late seventies, Hollywood has learned that their baby-booming audiences could not only handle strong horror and science fiction concepts, they craved them. Filmmakers everywhere went into overdrive. Like television today, there wasn’t a production house around that didn’t have at least one genre project in the making.

How things have changed. In the forties, for instance, one would find it difficult to name twenty good genre films of the decade but, since the late seventies, Hollywood has learned that their baby-booming audiences could not only handle strong horror and science fiction concepts, they craved them. Filmmakers everywhere went into overdrive. Like television today, there wasn’t a production house around that didn’t have at least one genre project in the making.

The first major genre event of the eighties was the first of the Star Wars sequels, Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Costing nearly three times as much as Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977), directed by Irvin Kershner and produced by George Lucas, The Empire Strikes Back shot up the box-office charts and firmly entrenched Lucas as the contemporary king of Hollywood. While the sequel lacked the pure simplicity of Star Wars, it was superior in every way, from characterisation to some of the most complex special effects ever seen, effects created by Lucas’s own facility dubbed Industrial Light & Magic.

The first major genre event of the eighties was the first of the Star Wars sequels, Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Costing nearly three times as much as Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977), directed by Irvin Kershner and produced by George Lucas, The Empire Strikes Back shot up the box-office charts and firmly entrenched Lucas as the contemporary king of Hollywood. While the sequel lacked the pure simplicity of Star Wars, it was superior in every way, from characterisation to some of the most complex special effects ever seen, effects created by Lucas’s own facility dubbed Industrial Light & Magic.

Popeye (1980) came as a complete surprise. A Disney-financed musical based on a cartoon character, and directed by Robert Altman? It seemed impossible, yet in many ways it was a triumph. Another pleasant surprise was Mel Brooks who, as producer, brought us such genre delights as Frances (1982), The Doctor And The Devils (1985), The Fly (1986) and, of course, The Elephant Man (1980), which introduced unsuspecting mainstream audiences to the work of David Lynch, who Mel aptly described as “like Jimmy Stewart – from Mars.”

Whether it’s because of its militancy or the exploding heads, or because of a shooting at one of its early screenings, Scanners (1980) became a surprise box-office success, David Cronenberg‘s biggest at the time, and led to several sequels and a cult reputation, all evidence of its enduring appeal. Most of Cronenberg’s films prey on the frailty of the human body and the deviousness of the human mind, and contain metaphors for society’s twisted perception of social mores and human nature. In The Fly, made while Cronenberg’s father was dying of cancer, Jeff Goldblum‘s humanity gives way to his baser nature as a fly’s genetic makeup gradually overtakes his body and, in Dead Ringers (1988), Jeremy Irons plays twin gynecologists who are attached psychologically until death do them part.

As an exquisite piece of glossy trash cinema, the c**k-teasing thrills of Dressed To Kill (1980) are particularly impossible to resist. Once more, Brian DePalma throws logic to the wind, setting his sights firmly on delivering one carefully orchestrated, neatly executed set-piece after another. Only this time, it all comes together. Even the dialogue (never his forte) is loaded all the way up to its carefully-shaved balls with absurdly provocative, often wickedly funny lines. John Carpenter‘s The Fog (1980) is a Gothic horror story about a mysterious mist which blankets a small coastal town, and from the fog emerges a band of ghosts intent on avenging their deaths one hundred years before. The film features the early effects work of Rob Bottin who also plays, under heavy makeup, the leader of the bloodthirsty apparitions.

Stanley Kubrick returned to the genre with his adaptation of Stephen King‘s bestseller The Shining (1980) starring Jack Nicholson in a completely manic-yet-mannered performance. Flash Gordon (1980) returned to the screen that year in a rather camp production from Dino De Laurentiis, demonstrating that he had learned little from his remake of King Kong (1976), another mega-buck failure. Christopher Reeve returned as the man of steel in Superman II (1980), a generally superior sequel also directed by Richard Donner, although sole credit was given to Richard Lester who directed certain comedic segments inserted as an afterthought. This unfortunate trend sadly continued with Lester’s Superman III (1983) in which the son of Krypton’s main adversary was comedian Richard Pryor.

Dario Argento‘s Inferno (1980), the sequel to Suspiria (1976) is largely set in a New York apartment building, the residence of the second of the Three Mothers, the Mother Of Darkness. Here, however, the bravura is faltering, the killings more random. This time around, it is difficult to identify with any one character, because one-by-one they are all demolished not long after they have been introduced. There is a straining for effect in the killings that comes close to being outright ludicrous. Mario Bava did the special effects and was responsible for the most haunting scenes. It’s become apparent that Argento is not terribly interested in linear narrative. For him, magic is arbitrary and inexplicable. The result is a fragmentation so extreme as to defy analysis of what it all might mean.

Dario Argento‘s Inferno (1980), the sequel to Suspiria (1976) is largely set in a New York apartment building, the residence of the second of the Three Mothers, the Mother Of Darkness. Here, however, the bravura is faltering, the killings more random. This time around, it is difficult to identify with any one character, because one-by-one they are all demolished not long after they have been introduced. There is a straining for effect in the killings that comes close to being outright ludicrous. Mario Bava did the special effects and was responsible for the most haunting scenes. It’s become apparent that Argento is not terribly interested in linear narrative. For him, magic is arbitrary and inexplicable. The result is a fragmentation so extreme as to defy analysis of what it all might mean.

Although Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981) proved to be the major success of its year, Friday The 13th Part II (1981) indicated there was still more mileage to be gained from the ‘Slice & Dice’ cycle, and John Landis and Joe Dante both proved that lycanthropy can be fun with their respective films An American Werewolf In London (1981) and The Howling (1981). A more serious entry in the horror stakes that year was Michael Wadleigh‘s Wolfen (1981), a story about a breed of super-intelligent wolves preying on the down-and-outs in New York’s decaying South Bronx.

Thanks to Paddy Chayefsky‘s script, Altered States (1981) reinterpreted the Jekyll & Hyde story for the eighties with near-hysterical direction by Ken Russell and some startling makeup effects created by Dick Smith. Clash Of The Titans (1981), which was backed by MGM, gave Ray Harryhausen the largest budget he has ever had to work with. It is quite a lavish production, with appearances by big stars such as Laurence Olivier, Burgess Meredith and Maggie Smith, but there is something sad about it, as if Harryhausen has been trapped in some sort of time-loop ever since The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958), the same awkwardly shambling monsters and trite plot looking more old-fashioned with each new film. The story is typically episodic, but his animation is as good as ever.

Thanks to Paddy Chayefsky‘s script, Altered States (1981) reinterpreted the Jekyll & Hyde story for the eighties with near-hysterical direction by Ken Russell and some startling makeup effects created by Dick Smith. Clash Of The Titans (1981), which was backed by MGM, gave Ray Harryhausen the largest budget he has ever had to work with. It is quite a lavish production, with appearances by big stars such as Laurence Olivier, Burgess Meredith and Maggie Smith, but there is something sad about it, as if Harryhausen has been trapped in some sort of time-loop ever since The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958), the same awkwardly shambling monsters and trite plot looking more old-fashioned with each new film. The story is typically episodic, but his animation is as good as ever.

Ambitiously promising “A Fear So Intense It Will Stay With You To The Grave And Beyond.” Dead And Buried (1981) is a minor eighties zombie gem that often shared drive-in double-billing with David Cronenberg‘s Scanners (1980). In the sleepy seaside town of Potter’s Bluff, New England, strangers aren’t wanted and are viciously mutilated by the local welcome wagon, who photograph their victim’s death throes with cheery relish. When a torched victim turns up seemingly alive and unscathed, the local sheriff (James Farantino) must confront the possibility that maybe death isn’t necessarily the end.

Ambitiously promising “A Fear So Intense It Will Stay With You To The Grave And Beyond.” Dead And Buried (1981) is a minor eighties zombie gem that often shared drive-in double-billing with David Cronenberg‘s Scanners (1980). In the sleepy seaside town of Potter’s Bluff, New England, strangers aren’t wanted and are viciously mutilated by the local welcome wagon, who photograph their victim’s death throes with cheery relish. When a torched victim turns up seemingly alive and unscathed, the local sheriff (James Farantino) must confront the possibility that maybe death isn’t necessarily the end.

John Carpenter returned to his first best genre, science fiction, with Escape From New York (1981). Tremendously good fun, it was nevertheless a bit of a disappointment, for by now people were expecting remarkable things with each new Carpenter film. Life began to look even grimmer for John after his next film, a remake of Howard Hawks’ production of The Thing From Another World (1951). Although It didn’t completely flop at the box office, it was not the success that Universal needed to recoup the production costs, which were said to be around fifteen million dollars. However, The Thing (1982) has since proven to be one of the great milestones in fantastic cinema, and its comparative failure at the box office could be a testament to its breaking of new ground.

The Evil Dead (1981) almost didn’t get released. Every major distributor passed on Sam Raimi‘s gore-fest, even Paramount, who had recently found success with Friday The 13th (1980). Raimi had just about given up hope when author Stephen King saw the film at the Cannes Film Festival and published a glowing review: “What Raimi achieves in The Evil Dead is a black rainbow of horror,” praising the simple story, effective makeup, and exhilarating cinematography, saying of Raimi’s fluid camera work, “Somebody ought to tell Kubrick, Spielberg, et al, that there’s really nothing to this stuff. Just bolt the camera to a two-by-four and run like hell.”

The failure of Ghost Story (1981) is mystifying, for it is based on a subtle, ironic book written by Stephen King collaborator Peter Straub, one of the most unusual horror novels of the last century. This should have provided a good basis for director John Irvin to work with, especially as he had previously shown, with his excellent television adaptation of John Le Carre’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, that he knew a thing or two about showing aging men confronted by resurrected secrets from the past. And he could hardly have had four more professional actors to work with than Fred Astaire, Melvyn Douglas, Douglas Fairbanks Junior and John Houseman.

Filmmaker George Romero began his longtime partnership with prolific author Stephen King in 1980. King is a scribe of course, not an actor, but is blessed with the singular talent of portraying an obnoxious redneck convincingly (probably because he’s had the misfortune to meet so many during his career), and Romero put King to work in his next two films: Knightriders (1981), a festival favourite about a group of modern-day jousters who reenact tournaments on motorcycles starring Ed Harris and Tom Savini, and the commercially successful Creepshow (1982), written by King himself, an anthology of tongue-in-cheek tales modeled after fifties pre-code horror comics.

Filmmaker George Romero began his longtime partnership with prolific author Stephen King in 1980. King is a scribe of course, not an actor, but is blessed with the singular talent of portraying an obnoxious redneck convincingly (probably because he’s had the misfortune to meet so many during his career), and Romero put King to work in his next two films: Knightriders (1981), a festival favourite about a group of modern-day jousters who reenact tournaments on motorcycles starring Ed Harris and Tom Savini, and the commercially successful Creepshow (1982), written by King himself, an anthology of tongue-in-cheek tales modeled after fifties pre-code horror comics.

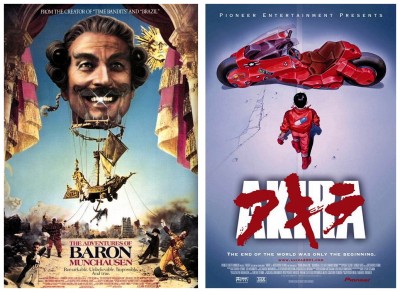

Peter Hyam‘s Outland (1981) was a big-budget effort, a film obviously inspired by the look of Alien (1979), although it came from a script that was pure B-grade western in origin, featuring Sean Connery as the new marshal of a mining colony on Io, one of the moons of Jupiter. The New Zealand film Strange Behaviour aka Dead Kids (1981) was a witty and promising directorial debut for Michael Laughlin, who had previously produced Two Lane Blacktop (1971) and went on to make the excellent science fiction movie Strange Invaders (1983), the second in his then-proposed trilogy. In a small mid-western town college town, a government research centre is investigating the effects of mental conditioning on local college students. This is connected with a bizarre series of gory murders. The explanation, involving a supposedly dead mad scientist, is conventional genre nonsense, but its themes are well done, and the script is consistently lively and believable. Reality taking flight in the midst of crisis is an everyday occurrence in the films of Terry Gilliam, the auteur behind Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1988). Brazil is definitely the darkest in his trilogy about the (supposedly) triumphant imagination. True, Sam’s nightmares are often revelations, but his daydreams are escapist and utterly conventional in a Walter Mitty kind of way, and the film’s true hero (Robert DeNiro) is literally smothered in paperwork and vanishes, the final figment of Sam’s exhausted mind.

Along with Steven Spielberg‘s charming fantasy E.T: The Extraterrestrial (1982), the year was chock-a-block full of remakes and sequels. Paul Schrader reworked Cat People (1982) into a sado-erotic feature complete with violence, gore and near-explicit sex. The crew of the starship Enterprise returned in Star Trek II The Wrath Of Khan (1982), a film which proved even more popular than its predecessor and cost less than a third to make. The horrors continued at Camp Crystal Lake in Friday The 13th Part III (1982) filmed in 3-D as part of a mini-revival of the dimensional process, and Australian ‘Ozploitation’ came of age with the international success of George Miller‘s Mad Max II The Road Warrior (1982).

Landis, Spielberg, Dante and Miller teamed up to make Twilight Zone The Movie (1983) with Dante’s and Miller’s episodes winning on points. Although made in 1982, the feature wasn’t released until the following year due to the on-set deaths of actor Vic Morrow and two children in a helicopter accident. The Spielberg-produced Poltergeist (1982), laden with special effects and some horrific shocks, caused a controversy of a different kind when it became known that credited director Tobe Hooper had some problems with his mercurial and seemingly tireless producer. But the public didn’t care about such in-fighting and flocked to see Poltergeist nevertheless.

There are reasons why Larry Cohen is considered one of the most original, subversive and eccentric of all the Hollywood independents. Since his subversion is usually carried out in low budget horror films, he is not seen as any threat to the establishment, but his films repay viewing and viewing again, for the extraordinary mileage he gets out of what, in other hands, would be bottom-of-the-barrel exploitation plot ideas. His contributions to the eighties include Q The Winged Serpent (1982), The Stuff (1985), Island Of The Alive (1987), Return To Salem’s Lot (1987), Maniac Cop (1988) and Wicked Stepmother (1989). I don’t have space here to describe them all in detail, but you probably wouldn’t believe me anyway.

There are reasons why Larry Cohen is considered one of the most original, subversive and eccentric of all the Hollywood independents. Since his subversion is usually carried out in low budget horror films, he is not seen as any threat to the establishment, but his films repay viewing and viewing again, for the extraordinary mileage he gets out of what, in other hands, would be bottom-of-the-barrel exploitation plot ideas. His contributions to the eighties include Q The Winged Serpent (1982), The Stuff (1985), Island Of The Alive (1987), Return To Salem’s Lot (1987), Maniac Cop (1988) and Wicked Stepmother (1989). I don’t have space here to describe them all in detail, but you probably wouldn’t believe me anyway.

Ingmar Bergman‘s final film as director, Fanny And Alexander (1982), is directly concerned with what Ingmar Bergman is all about: The illusion of miracles being real, and the possibility that in one way they are just as real as our everyday lives, which are themselves subject to all the illusions of perception. We see what we want to see. The cult musical Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1982) is Alan Parker‘s visual interpretation of the rock opera by the band Pink Floyd (Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Nick Mason and Richard Wright). The original album’s overriding themes are based on the causes and implications of self-imposed isolation, symbolised by the metaphorical wall of the title. The movie is unrelentingly downbeat and at times quite gruesome, the cinematography by Peter Bizou is extremely impressive, many individual scenes have undeniable power, and the animation sequences by British political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe are truly extraordinary.

The Beastmaster (1982), starring Marc Singer and Tanya Roberts, was a low-budget attempt to cash-in on the success on Conan The Barbarian (1982) with plenty of swords, sorcery, sandals and semi-nude girls. Occasionally violent but it’s all in the name of good fun, and the above-average soundtrack by Lee Holdridge helps to give an epic feel to the proceedings about a man who can control animals in his bid to depose an evil ruler. Jim Henson‘s The Dark Crystal (1982) was a failed experimental fantasy about the quest for a magical crystal shard that will set the world right. Brimming with good ideas, but the complete lack of human characters has a distancing effect on the action leading to an almost complete lack of audience identification. Despite much of its huge budget spent to develop the various animatronic creatures, the very nature of puppetry gives the entire film a strange claustrophobic ambience.

Blade Runner (1982) depicts a dystopian Los Angeles in 2019 in which genetically engineered organic robots called replicants are manufactured by the all-powerful Tyrell Corporation. The plot focuses on a brutal and cunning group of recently escaped replicants hiding in Los Angeles and the burnt-out expert Blade Runner Rick Deckard, who reluctantly agrees to take on one more assignment to hunt them down. Ridley Scott‘s vision of the future was like no other, and the intelligent metaphysical nature of the film has audiences guessing for years. The screenplay by David Peoples and Hampton Fancher is very loosely based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?

Blade Runner (1982) depicts a dystopian Los Angeles in 2019 in which genetically engineered organic robots called replicants are manufactured by the all-powerful Tyrell Corporation. The plot focuses on a brutal and cunning group of recently escaped replicants hiding in Los Angeles and the burnt-out expert Blade Runner Rick Deckard, who reluctantly agrees to take on one more assignment to hunt them down. Ridley Scott‘s vision of the future was like no other, and the intelligent metaphysical nature of the film has audiences guessing for years. The screenplay by David Peoples and Hampton Fancher is very loosely based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?

Max Renn, the hero of Videodrome (1982), uses the catharsis argument during a scene set in a talk-show interview, and there director David Cronenberg shows it as an obviously glib response from a man unwilling to confront his deeper motivations. Almost immediately after Videodrome, however, he proved that, if he forced himself, he could work within the conventional movie system. One imagines that, if he had not proved this, the financing of each new film would have become more and more difficult. His adaptation of Stephen King‘s novel The Dead Zone (1983) is not a typical Cronenberg movie, but it is nevertheless an extremely clever adaptation.

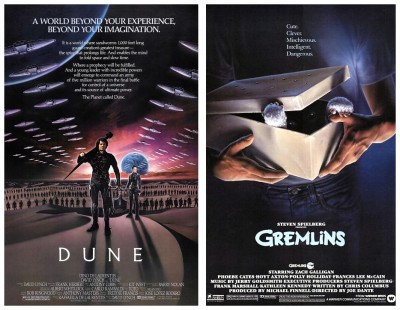

The following two years saw the continuation of Spielberg’s and Lucas’s domination of the genre. With Star Wars VI: The Return Of The Jedi (1983) producer Lucas tied up all the loose ends from the previous two Star Wars films in a somewhat haphazard fashion, though it remains a one of the most dazzling displays of special effects ever seen on the silver screen, a film that virtually exists for its effects at the expense of plot and characterisation. Spielberg returned with two films, one as producer – Gremlins (1984) directed by Joe Dante in his usual eccentric fashion – and one as director. If audiences found Raiders Of The Lost Ark exciting, then Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1983) should have blasted them out of their seats with a rollercoaster ride of a movie in which nothing gets in the way of the non-stop action – not even logic.

The following two years saw the continuation of Spielberg’s and Lucas’s domination of the genre. With Star Wars VI: The Return Of The Jedi (1983) producer Lucas tied up all the loose ends from the previous two Star Wars films in a somewhat haphazard fashion, though it remains a one of the most dazzling displays of special effects ever seen on the silver screen, a film that virtually exists for its effects at the expense of plot and characterisation. Spielberg returned with two films, one as producer – Gremlins (1984) directed by Joe Dante in his usual eccentric fashion – and one as director. If audiences found Raiders Of The Lost Ark exciting, then Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1983) should have blasted them out of their seats with a rollercoaster ride of a movie in which nothing gets in the way of the non-stop action – not even logic.

Special effects supervisor Doug Trumbull‘s second film as director was Brainstorm (1983), a science fiction thriller starring Christopher Walken and Natalie Wood about an invention that can record physical, emotional and intellectual sensations as they are experienced by one individual, then allow them to be experienced by another. Unfortunately, Natalie Wood’s passing mid-production meant a lot of changes and clever editing which, on the whole, works. As if chastened by the critical and commercial failure of The Thing (1982), John Carpenter‘s next venture was restrained in the extreme, but nonetheless effective for it. Christine (1983), adapted from the popular Stephen King novel, told the story of a car apparently possessed of a mind of her own. Bought as a junkyard jalopy by a wimpish put-upon teenager, the 1958 Plymouth Fury – when lovingly restored by the boy – becomes a jealous and murderously demonic vehicle of vengeance.

Luc Besson‘s first feature film The Final Combat (1983) takes place in a post-apocalyptic future where only a few humans are left. No one is able to speak – the film contains no dialogue – and characters communicate non-verbally. A determined loner befriends a reclusive older man and these two battle against vicious thugs for food, shelter and life itself. Tony Scott‘s directorial debut was The Hunger (1983), an arty, kinky, and visually cold film starring Catherine Deneuve as a seductive vampire whose old boyfriend (David Bowie) is about to disintegrate, so she picks a new lover played by Susan Sarandon.

The British-made Krull (1983) was a mega-budget mega-flop. It might have seemed a good idea to combine Errol Flynn-style swashbuckling with Star Wars-style special effects, but Stanford Sherman‘s script is such a jumble of ideas and styles, and Peter Yates‘ direction is so bland that the film falls apart within the first ten minutes. James Horner‘s soundtrack is powerful, an obvious attempt to distract the viewer from the feature’s numerous shortcomings. Scarface (1983) is loosely based on Howard Hawks original 1932 film, and tells the story of a fictional Cuban refugee named Tony Montana who arrives in Miami in 1980, and becomes a gangster against the backdrop of the eighties cocaine boom. The film chronicles his rise to the top of Miami’s criminal underworld and subsequent downfall in tragic Greek fashion. “Say hello to my little friend!” Al Pacino‘s vicious drug-dealer Montana has been an icon for gangsters all over the world, which may not be the kind of cult that director Brian DePalma or writer Oliver Stone was expecting.

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) is the first fantasy film made by Jack Clayton since The Innocents (1961). Produced by Disney, it went through tremendous upheavals during production, with Clayton being overruled on many key issues: A new, embarrassingly sentimental ending was shot, a lot of special effects were inserted, a new musical score was commissioned from James Horner, and a new scene which Clayton hated, when the two boys are menaced in their bedroom by hundreds of tarantulas. All this held up the film’s release until 1983 but, despite its chaotic creation, Something Wicked This Way Comes actually turned out to be a very good film. Wargames (1983) starred Matthew Broderick as a young computer whiz-kid who thinks he’s linking to a game manufacturer’s computer accidentally starts World War III when he decides to play a game called Global Thermonuclear Warfare. Though the movie contains almost no violence or any other sensationalistic content, it still grips the viewer.

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) is the first fantasy film made by Jack Clayton since The Innocents (1961). Produced by Disney, it went through tremendous upheavals during production, with Clayton being overruled on many key issues: A new, embarrassingly sentimental ending was shot, a lot of special effects were inserted, a new musical score was commissioned from James Horner, and a new scene which Clayton hated, when the two boys are menaced in their bedroom by hundreds of tarantulas. All this held up the film’s release until 1983 but, despite its chaotic creation, Something Wicked This Way Comes actually turned out to be a very good film. Wargames (1983) starred Matthew Broderick as a young computer whiz-kid who thinks he’s linking to a game manufacturer’s computer accidentally starts World War III when he decides to play a game called Global Thermonuclear Warfare. Though the movie contains almost no violence or any other sensationalistic content, it still grips the viewer.

Produced for only $350,000, a tiny fraction of the spectacular budgets afforded to science fiction films at the time, The Brother From Another Planet (1984) stars Joe Morton, Steve James, Leonard Jackson, Bill Cobbs, Fisher Stevens, with David Strathairn and John Sayles himself as a pair of hilarious alien Men In Black sent to apprehend our hero. John Sayles, like so many other great filmmakers, began his career with the crux of our civilisation, Roger Corman. After writing such cult classics as Piranha (1978), Alligator (1980), Battle Beyond The Stars (1980) and The Howling (1981) for Corman, Sayles used his earnings and learnings to fund his own feature film, The Return Of The Secaucus Seven (1979).

Over the last three decades, director Wes Craven has become an efficient, dependable film-maker who is obviously comfortable behind the camera, but there’s no flair, no style, and very little imagination when it comes to horror. Freddy Krueger is really his only memorable contribution to the genre. Krueger’s first appearance was in A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984), which focused on the ghost of Krueger trying to kill young Nancy and her friends in their dreams, killing all but Nancy, who defeats him by pulling him into the real world. She sets up a series of booby traps worthy of Macauley Culkin and finally strips him of his powers by refusing to be afraid. Krueger returned in A Nightmare On Elm Street II Freddy’s Revenge (1985), haunting the family who had moved into Nancy’s old house. Each subsequent sequel became more laughable, and after A Nightmare On Elm Street III The Dream Warriors (1987), A Nightmare On Elm Street IV The Dream Master (1988), and A Nightmare On Elm Street V The Dream Child (1989), the character of Freddy Krueger went from terrifying supernatural child-killer to a jovial friend of innocent children everywhere, scaring teenagers who might be on the wrong path in life.

Over the last three decades, director Wes Craven has become an efficient, dependable film-maker who is obviously comfortable behind the camera, but there’s no flair, no style, and very little imagination when it comes to horror. Freddy Krueger is really his only memorable contribution to the genre. Krueger’s first appearance was in A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984), which focused on the ghost of Krueger trying to kill young Nancy and her friends in their dreams, killing all but Nancy, who defeats him by pulling him into the real world. She sets up a series of booby traps worthy of Macauley Culkin and finally strips him of his powers by refusing to be afraid. Krueger returned in A Nightmare On Elm Street II Freddy’s Revenge (1985), haunting the family who had moved into Nancy’s old house. Each subsequent sequel became more laughable, and after A Nightmare On Elm Street III The Dream Warriors (1987), A Nightmare On Elm Street IV The Dream Master (1988), and A Nightmare On Elm Street V The Dream Child (1989), the character of Freddy Krueger went from terrifying supernatural child-killer to a jovial friend of innocent children everywhere, scaring teenagers who might be on the wrong path in life.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) is an absolutely stunning adaptation of George Orwell‘s novel which captures every note of bleak despair found within those pages. John Hurt looks positively emaciated as the forlorn Winston Smith, the tragic figure who dares to fall in love in a totalitarian society where emotions are outlawed. Richard Burton, in his final film role, makes a frightening interrogator indeed. Wild, weird and unpredictable, Repo Man (1984) stars Emilio Estevez as a young man who gets into the repossession racket. Under the tutelage of Harry Dean Stanton, Estevez learns how to steal cars from people who haven’t kept up with their payments. Meanwhile, bizarre events lead them to an encounter with what may be space aliens. Those of you who occasionally like to watch something different are gonna love this one.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) is an absolutely stunning adaptation of George Orwell‘s novel which captures every note of bleak despair found within those pages. John Hurt looks positively emaciated as the forlorn Winston Smith, the tragic figure who dares to fall in love in a totalitarian society where emotions are outlawed. Richard Burton, in his final film role, makes a frightening interrogator indeed. Wild, weird and unpredictable, Repo Man (1984) stars Emilio Estevez as a young man who gets into the repossession racket. Under the tutelage of Harry Dean Stanton, Estevez learns how to steal cars from people who haven’t kept up with their payments. Meanwhile, bizarre events lead them to an encounter with what may be space aliens. Those of you who occasionally like to watch something different are gonna love this one.

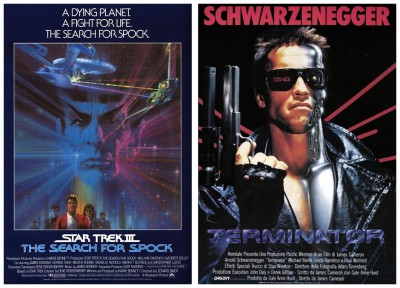

Seemingly in an effort to plead for Hollywood’s forgiveness after recent box-office failures, John Carpenter made Starman (1984) starring Jeff Bridges in an award-winning performance as an alien who falls in love with Earth girl Karen Allen. Starman is best described as a fairy tale for adults, but the kiddies will enjoy it too. The Terminator (1984) is played with relish by Arnold Schwarzenegger, a cyborg assassin sent back in time from the year 2029 to 1984 to kill Sarah Connor, and Kyle Reese is a soldier from the future sent back in time to protect her. James Cameron‘s bloody, extraordinarily imaginative science fiction slammer topped the American box office and helped launch the film careers of Cameron, Schwarzenegger and just about everyone else involved. It received mixed reviews from critics upon its release but, in 2008, The Terminator was selected by the Library Of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, being deemed culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.

Seemingly in an effort to plead for Hollywood’s forgiveness after recent box-office failures, John Carpenter made Starman (1984) starring Jeff Bridges in an award-winning performance as an alien who falls in love with Earth girl Karen Allen. Starman is best described as a fairy tale for adults, but the kiddies will enjoy it too. The Terminator (1984) is played with relish by Arnold Schwarzenegger, a cyborg assassin sent back in time from the year 2029 to 1984 to kill Sarah Connor, and Kyle Reese is a soldier from the future sent back in time to protect her. James Cameron‘s bloody, extraordinarily imaginative science fiction slammer topped the American box office and helped launch the film careers of Cameron, Schwarzenegger and just about everyone else involved. It received mixed reviews from critics upon its release but, in 2008, The Terminator was selected by the Library Of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, being deemed culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.

With the end of 1984 came yet another adventure for Captain Kirk and company with Star Trek III The Search For Spock (1984) directed by ol’ pointy ears himself, Leonard Nimoy, and Christopher Reeve finally decided enough was enough and refused a fat pay cheque to make a token appearance in the rather ham-fisted Supergirl (1984). Arnold Schwarzenegger was back flexing his muscles in tandem with fashion-model pop-singer Grace Jones in the inevitable sequel to Conan The Barbarian (1982) entitled Conan The Destroyer (1984). Speaking of pop music, Sting made his genre debut in David Lynch‘s forty million dollar epic Dune (1984) based on Frank Herbert‘s cult science fiction novel, and Daryl Hannah, who played one of the rogue replicants seen in Blade Runner (1982), delighted everyone with her performance as a mermaid in Ron Howard‘s Splash (1984).

With the end of 1984 came yet another adventure for Captain Kirk and company with Star Trek III The Search For Spock (1984) directed by ol’ pointy ears himself, Leonard Nimoy, and Christopher Reeve finally decided enough was enough and refused a fat pay cheque to make a token appearance in the rather ham-fisted Supergirl (1984). Arnold Schwarzenegger was back flexing his muscles in tandem with fashion-model pop-singer Grace Jones in the inevitable sequel to Conan The Barbarian (1982) entitled Conan The Destroyer (1984). Speaking of pop music, Sting made his genre debut in David Lynch‘s forty million dollar epic Dune (1984) based on Frank Herbert‘s cult science fiction novel, and Daryl Hannah, who played one of the rogue replicants seen in Blade Runner (1982), delighted everyone with her performance as a mermaid in Ron Howard‘s Splash (1984).

Budgeted at $19 million, Back To The Future (1985) has grossed a whopping $350 million worldwide and entered the annals of popular culture since its release. Given its phenomenal success, a sequel was inevitable, however it would be almost five years before cast and crew would reunite for part two. Unlike the visionary George Lucas, Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale had not conceived their time-travel enterprise as a franchise. The flying car at the end was intended as a gag only – Zemeckis and Gale never seriously considered a sequel, all they were worried about was breaking even at the box office. Dario Argento made Creepers aka Phenomena (1985) between Tenebrae (1982) and Opera (1987), but it’s more like his earlier classic Suspiria (1977). Creepers was the first film to utilise the new science of Forensic Entomology, so if your flesh is creeping right now, well, I’m hardly in a position to sympathise, am I?

Budgeted at $19 million, Back To The Future (1985) has grossed a whopping $350 million worldwide and entered the annals of popular culture since its release. Given its phenomenal success, a sequel was inevitable, however it would be almost five years before cast and crew would reunite for part two. Unlike the visionary George Lucas, Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale had not conceived their time-travel enterprise as a franchise. The flying car at the end was intended as a gag only – Zemeckis and Gale never seriously considered a sequel, all they were worried about was breaking even at the box office. Dario Argento made Creepers aka Phenomena (1985) between Tenebrae (1982) and Opera (1987), but it’s more like his earlier classic Suspiria (1977). Creepers was the first film to utilise the new science of Forensic Entomology, so if your flesh is creeping right now, well, I’m hardly in a position to sympathise, am I?

In James Cameron‘s Aliens (1986), fifty-seven years have passed during Ripley’s deep-space sleep. She wakes to learn planet LV-426 – where the crew of the ill-fated Nostromo first encountered the nasty extraterrestrial – has been colonised. Then communications are lost with the colonists. This is one sequel that is equal to, yet totally different from, the original. Blue Velvet (1986) centres on college student Jeffrey who comes across a human ear in a field in his hometown of Lumberton. He proceeds to investigate the ear with help from high school student Sandy, who provides him with information and leads from her father, a local police detective. Jeffrey’s investigation draws him deeper into his hometown’s seedy underworld, forming a sexual relationship with an alluring torch singer, and uncovering criminal Frank Booth who indulges in drugs and sexual violence. This weird, surreal, genre-bending head-trip from auteur David Lynch spurred on a huge cult in the eighties, and served as the unofficial starting point for his television series Twin Peaks, which practically redefined television in the nineties.

In James Cameron‘s Aliens (1986), fifty-seven years have passed during Ripley’s deep-space sleep. She wakes to learn planet LV-426 – where the crew of the ill-fated Nostromo first encountered the nasty extraterrestrial – has been colonised. Then communications are lost with the colonists. This is one sequel that is equal to, yet totally different from, the original. Blue Velvet (1986) centres on college student Jeffrey who comes across a human ear in a field in his hometown of Lumberton. He proceeds to investigate the ear with help from high school student Sandy, who provides him with information and leads from her father, a local police detective. Jeffrey’s investigation draws him deeper into his hometown’s seedy underworld, forming a sexual relationship with an alluring torch singer, and uncovering criminal Frank Booth who indulges in drugs and sexual violence. This weird, surreal, genre-bending head-trip from auteur David Lynch spurred on a huge cult in the eighties, and served as the unofficial starting point for his television series Twin Peaks, which practically redefined television in the nineties.

In Star Trek IV The Voyage Home (1986) our stalwart heroes journey back to Earth in their ‘borrowed’ enemy spacecraft just in time to witness a new tragedy in the making – an alien deep-space probe is disrupting our planet’s atmosphere by broadcasting a message that nobody understands. When Spock identifies the ‘language’ as that of the humpback whale, extinct in the twenty-third century, Kirk leads his crew back to the twentieth century in an attempt to locate two of the great mammals and assign them to translator duties. Charming and lighthearted, the fourth Star Trek film was the most accessible to mainstream audiences, which was reflected at the box-office.

In Star Trek IV The Voyage Home (1986) our stalwart heroes journey back to Earth in their ‘borrowed’ enemy spacecraft just in time to witness a new tragedy in the making – an alien deep-space probe is disrupting our planet’s atmosphere by broadcasting a message that nobody understands. When Spock identifies the ‘language’ as that of the humpback whale, extinct in the twenty-third century, Kirk leads his crew back to the twentieth century in an attempt to locate two of the great mammals and assign them to translator duties. Charming and lighthearted, the fourth Star Trek film was the most accessible to mainstream audiences, which was reflected at the box-office.

Peter Jackson‘s first feature Bad Taste (1987) is the one film that demonstrates that all you need is some film equipment, your friends and family, and about 180 free weekends. In fact, the filming went on for so long that actor Craig Smith got married and divorced during the filming. If making Bad Taste had taught Peter Jackson anything, it was you can get away with a lame story and no real actors, as long as you can smear special effects over the top, thus ensuring his inevitable Hollywood career. In Adrian Lyne‘s Fatal Attraction (1987), Michael Douglas, for no obvious reason, cheats on his beautiful wife Beth within the first ten minutes with a business associate. His motives are unclear, apart from the fact that temptation seems to get the better of him. Whether he’s rebelling against middle-class complacency or just a hedonist, Fatal Attraction is a mainstream American movie that embraced an interesting existentialism that the viewer – and a legion of feminists – were apparently unprepared for at the time of its release.

Peter Jackson‘s first feature Bad Taste (1987) is the one film that demonstrates that all you need is some film equipment, your friends and family, and about 180 free weekends. In fact, the filming went on for so long that actor Craig Smith got married and divorced during the filming. If making Bad Taste had taught Peter Jackson anything, it was you can get away with a lame story and no real actors, as long as you can smear special effects over the top, thus ensuring his inevitable Hollywood career. In Adrian Lyne‘s Fatal Attraction (1987), Michael Douglas, for no obvious reason, cheats on his beautiful wife Beth within the first ten minutes with a business associate. His motives are unclear, apart from the fact that temptation seems to get the better of him. Whether he’s rebelling against middle-class complacency or just a hedonist, Fatal Attraction is a mainstream American movie that embraced an interesting existentialism that the viewer – and a legion of feminists – were apparently unprepared for at the time of its release.

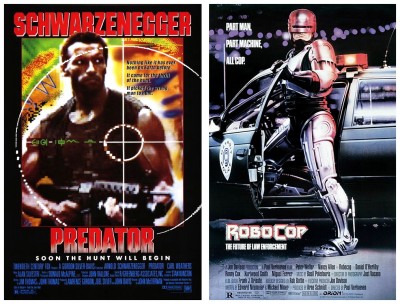

Beginning with a seemingly routine reconnaissance mission for Arnold Schwarzenegger and his crack team of soldiers, Predator (1987) switches genre gears smoothly when a mysterious camouflaged entity begins picking off the squad one at a time. Hemmed into rugged bushland, the actors perspire in an aesthetically pleasing manner for John McTiernan‘s mobile camera which negotiates the terrain in slow menacing moves. Robocop (1987) was, at the time, the ultimate superhero movie, inspired by (among many other things) Judge Dredd comics. A stylish and stylised cop thriller set in the near future, it concerns a mortally wounded policeman (Peter Weller) who is melded with a machine to become the ultimate defender of justice. Directed by Paul Verhoeven with his typical tongue-in-cheek humour, Robocop spawned a cartoon series, a cable miniseries, and at least three sequels.

Beginning with a seemingly routine reconnaissance mission for Arnold Schwarzenegger and his crack team of soldiers, Predator (1987) switches genre gears smoothly when a mysterious camouflaged entity begins picking off the squad one at a time. Hemmed into rugged bushland, the actors perspire in an aesthetically pleasing manner for John McTiernan‘s mobile camera which negotiates the terrain in slow menacing moves. Robocop (1987) was, at the time, the ultimate superhero movie, inspired by (among many other things) Judge Dredd comics. A stylish and stylised cop thriller set in the near future, it concerns a mortally wounded policeman (Peter Weller) who is melded with a machine to become the ultimate defender of justice. Directed by Paul Verhoeven with his typical tongue-in-cheek humour, Robocop spawned a cartoon series, a cable miniseries, and at least three sequels.

The flagship of Japanese anime, Akira (1988), was directed by Katsuhiro Otomo based on his own popular comic book series. This spectacular and violent film takes place in twenty-first century post-World War III Japan, where the member of a motorcycle gang becomes an unwilling guinea pig in a scientific experiment that backfires. Vincent Ward‘s directorial debut was The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988), a visionary film that involves a medieval quest through time. The film opens in Cumbria 1348 in the midst of the terrifying Black Plague. A village of miners tries to appease their vengeful god by traveling a vast distance to fulfill a child’s vision. The adventurers travel through the Earth and surface in a modern-day New Zealand town.

The flagship of Japanese anime, Akira (1988), was directed by Katsuhiro Otomo based on his own popular comic book series. This spectacular and violent film takes place in twenty-first century post-World War III Japan, where the member of a motorcycle gang becomes an unwilling guinea pig in a scientific experiment that backfires. Vincent Ward‘s directorial debut was The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988), a visionary film that involves a medieval quest through time. The film opens in Cumbria 1348 in the midst of the terrifying Black Plague. A village of miners tries to appease their vengeful god by traveling a vast distance to fulfill a child’s vision. The adventurers travel through the Earth and surface in a modern-day New Zealand town.

Willow (1988), written and produced by George Lucas, with midgets, crazy witches, gorgeous New Zealand locales, big Industrial Light & Magic special effects, Val Kilmer when he actually seemed interested in acting and, at the helm, nice guy Ron Howard, a long way from his meagre beginnings as director of modestly budgeted fare for Roger Corman. It’s just so crazy it might just work! Or not, as the case may be. While the production is handsomely mounted, the slightness and episodic nature of the story, the lumpy pacing, dated special effects, and the muted cinematography from the usually reliable Adrian Biddle fails to really generate much excitement.

As one might expect from James Cameron, the numerous action set-pieces in The Abyss (1989) are, without exception, state-of-the-art masterworks, all the more remarkable for being filmed in extremely demanding underwater conditions. By contrast, the film’s narrative, which deals with an encounter with aliens during an attempt to salvage a downed submarine, proved more contentious. Both Universal and 20th Century Fox passed on making Evil Dead II Dead By Dawn (1989), but a deal was struck with Dino De Laurentiis to film the sequel on a budget of only US$3.7 million. With such a small budget to work with, director Sam Raimi planned to use stock footage from The Evil Dead (1981) to recount the original film’s plot in flashbacks. Unfortunately, he was unable to negotiate a favourable deal with Films Around The World to use footage from his own film, opting instead to re-film the action of the original.

Slipstream (1989) was directed by Steven Lisberger, the same hack who brought us Tron (1982) which, although very pretty, was bad science and worse fiction. Given Tron’s eventual popularity, you’d think it would have launched Lisberger’s film-making career. It didn’t. Slipstream is a post-apocalyptic science fiction film which has a remarkable cast featuring Mark Hamill, Bob Peck, Bill Paxton, Robbie Coltrane, Kitty Aldridge, Ben Kingsley and F. Murray Abraham, yet Slipstream is virtually a forgotten film. Tetsuo The Iron Man (1989) is a hyperkinetic cult film about an office worker who mutates into a half-metal being. Grotesque makeup, stop-motion animation and time-lapse photography make this the perfect visual equivalent of industrial music. Director Shinya Tsukamoto has made at least two sequels since. Well, that’s about it for the eighties. I have no doubt that I’ve missed your favourite titles but, since you’re still reading this, I know I can count on having your company again when I pick another forgotten fragment of filmic fluff from cinema’s lint trap next week for…Horror News! Toodles!

Also: see

1920s Genre Films

1930s Genre Films

1940s Genre Films

1950s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1970s Genre Films

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews