While the commercial form of genre cinema was being shaped, first in Germany in the twenties and then Hollywood in the thirties, it was receiving a rather different kind of input from several non-commercial intellectual filmmakers in Europe. Yet it was not so very long before the influence of the artistic movement of surrealism was making its way into the commercial cinema as well. Surrealism as a separately definable movement grew up around 1924, evolving in part from the earlier Dada movement, which stressed the absurd in art. With hindsight we can see that several aspects of surrealism had existed even earlier, though not under that name, notably in the French symbolists of the nineteenth century.

While the commercial form of genre cinema was being shaped, first in Germany in the twenties and then Hollywood in the thirties, it was receiving a rather different kind of input from several non-commercial intellectual filmmakers in Europe. Yet it was not so very long before the influence of the artistic movement of surrealism was making its way into the commercial cinema as well. Surrealism as a separately definable movement grew up around 1924, evolving in part from the earlier Dada movement, which stressed the absurd in art. With hindsight we can see that several aspects of surrealism had existed even earlier, though not under that name, notably in the French symbolists of the nineteenth century.

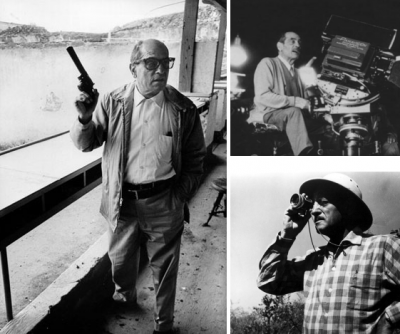

Horror News is not the place to embark on a lengthy definition of what precisely can or can’t be defined as surrealism. But I can point to four familiar qualities of surrealism that create at least some of its characteristic atmosphere, and you’ll find all of these in one movie, the first truly surrealist feature film, L’Âge d’Or (1930), directed by Luis Buñuel. The surrealist painter Salvador Dali is given a co-writing credit but in fact had little to do with the film, though he was a genuine co-writer on Buñuel’s first surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou (1929). These are the four qualities:

Horror News is not the place to embark on a lengthy definition of what precisely can or can’t be defined as surrealism. But I can point to four familiar qualities of surrealism that create at least some of its characteristic atmosphere, and you’ll find all of these in one movie, the first truly surrealist feature film, L’Âge d’Or (1930), directed by Luis Buñuel. The surrealist painter Salvador Dali is given a co-writing credit but in fact had little to do with the film, though he was a genuine co-writer on Buñuel’s first surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou (1929). These are the four qualities:

1. Surrealism is bizarre. There is no acknowledgment of the primacy of ‘reality’ and, by implication, there is no such thing as ‘reality’ anyway. Both within scenes and in the juxtaposition of different scenes, there is a strong element of the grotesque, the absurd, the arbitrary. Thus in L’Âge d’Or (The Golden Age), the passionate hero Gaston Modot hurls first a giraffe and then a bishop from a window (grotesqueness within a scene). The film then dissolves to a medieval castle from which are emerging four aristocrats clearly modeled on the Marquis De Sade and his entourage (arbitrariness of juxtaposition). The De Sade figure looks exactly like Christ (grotesqueness within a scene).

1. Surrealism is bizarre. There is no acknowledgment of the primacy of ‘reality’ and, by implication, there is no such thing as ‘reality’ anyway. Both within scenes and in the juxtaposition of different scenes, there is a strong element of the grotesque, the absurd, the arbitrary. Thus in L’Âge d’Or (The Golden Age), the passionate hero Gaston Modot hurls first a giraffe and then a bishop from a window (grotesqueness within a scene). The film then dissolves to a medieval castle from which are emerging four aristocrats clearly modeled on the Marquis De Sade and his entourage (arbitrariness of juxtaposition). The De Sade figure looks exactly like Christ (grotesqueness within a scene).

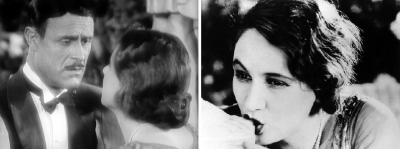

2. Surrealism pays homage to the subconscious. It is clearly post-Freudian. L’Âge d’Or has the mysteriousness of dreams, and Modot’s imaginings are given a kind of dream-reality. For example, he imagines the woman he loves sitting on a spotlessly clean lavatory, then cuts to a shot of bubbling lava/mud. Make of this what you will, his imagination is clearly heated.

2. Surrealism pays homage to the subconscious. It is clearly post-Freudian. L’Âge d’Or has the mysteriousness of dreams, and Modot’s imaginings are given a kind of dream-reality. For example, he imagines the woman he loves sitting on a spotlessly clean lavatory, then cuts to a shot of bubbling lava/mud. Make of this what you will, his imagination is clearly heated.

3. Surrealism is subversive. Against repression, it slaps the faces of the bourgeois and is politically, religiously and sexually radical. L’Âge d’Or is full of examples of all these. Near the beginning, a boatload of dignitaries arrives at a beach where some kind of important celebration is about to take place. But this is interrupted by the orgasmic cries of Modot and his girlfriend rolling in mud in a passionately sexual embrace. In a later scene, Modot is called from a tryst to answer the telephone while his girlfriend, frustrated, sucks the toes of a classical statue. Buñuel was successful in his attempt to shock, and the film was banned in many countries for many years.

3. Surrealism is subversive. Against repression, it slaps the faces of the bourgeois and is politically, religiously and sexually radical. L’Âge d’Or is full of examples of all these. Near the beginning, a boatload of dignitaries arrives at a beach where some kind of important celebration is about to take place. But this is interrupted by the orgasmic cries of Modot and his girlfriend rolling in mud in a passionately sexual embrace. In a later scene, Modot is called from a tryst to answer the telephone while his girlfriend, frustrated, sucks the toes of a classical statue. Buñuel was successful in his attempt to shock, and the film was banned in many countries for many years.

4. Surrealism looks at its subjects with a concentrated child-like stare. No matter how innocent or inappropriate the object of the gaze might appear, the hypnotic intensity of the scrutiny gives it a kind of abstract significance . We do not know what it means, but we know it means something, and later we might find out. thus L’Âge d’Or begins with a documentary-style shot in close-up of three scorpions struggling together. At first, this seems to have nothing to do with what follows: A bandit (played by Max Ernst) witnesses the arrival of four archbishops on a rocky shore, followed by a shot of their skeletons on the rocks, but the effect of the image nevertheless pervades the film. It is as if all of life has the matter-of-fact insect-like cruelty of the scorpions. In fact, surrealism is very often cynical and evokes images of a kind of cosmic absurd cruelty that wounds us, not deliberately but indifferently.

4. Surrealism looks at its subjects with a concentrated child-like stare. No matter how innocent or inappropriate the object of the gaze might appear, the hypnotic intensity of the scrutiny gives it a kind of abstract significance . We do not know what it means, but we know it means something, and later we might find out. thus L’Âge d’Or begins with a documentary-style shot in close-up of three scorpions struggling together. At first, this seems to have nothing to do with what follows: A bandit (played by Max Ernst) witnesses the arrival of four archbishops on a rocky shore, followed by a shot of their skeletons on the rocks, but the effect of the image nevertheless pervades the film. It is as if all of life has the matter-of-fact insect-like cruelty of the scorpions. In fact, surrealism is very often cynical and evokes images of a kind of cosmic absurd cruelty that wounds us, not deliberately but indifferently.

L’Âge d’Or has its flaws, and it’s easy to find parts of it pretentious, but it must surely be one of the most important genre films ever made. All of these qualities of surrealism re-emerge again and again in genre cinema, firstly in consciously artistic films made for the intelligentsia, and later in commercial films, especially horror movies. Some examples of the former include Zero de Conduite (1933), Cocteau’s Orphee (1950) and Rivette’s Celine And Julie Go Boating (1974). Horror films that use surrealistic devices include Lynch’s Eraserhead (1976), Borowczyk’s The Beast (1975) and Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1971). But many other horror films are surrealist also, especially Italian giallos like Argento’s Inferno (1980) and Fulci’s The Beyond (1981). Others might even include Cohen’s It’s Alive (1973), Coscarelli’s Phantasm aka The Never Dead (1978) and Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1982). Polish directors seem especially to thrive on surrealist imagery, examples being Zulawski’s Possession (1981), Skolimowski’s The Shout (1978) and practically everything made by Roman Polanski. It is also very strong in German cinema.

L’Âge d’Or has its flaws, and it’s easy to find parts of it pretentious, but it must surely be one of the most important genre films ever made. All of these qualities of surrealism re-emerge again and again in genre cinema, firstly in consciously artistic films made for the intelligentsia, and later in commercial films, especially horror movies. Some examples of the former include Zero de Conduite (1933), Cocteau’s Orphee (1950) and Rivette’s Celine And Julie Go Boating (1974). Horror films that use surrealistic devices include Lynch’s Eraserhead (1976), Borowczyk’s The Beast (1975) and Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1971). But many other horror films are surrealist also, especially Italian giallos like Argento’s Inferno (1980) and Fulci’s The Beyond (1981). Others might even include Cohen’s It’s Alive (1973), Coscarelli’s Phantasm aka The Never Dead (1978) and Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1982). Polish directors seem especially to thrive on surrealist imagery, examples being Zulawski’s Possession (1981), Skolimowski’s The Shout (1978) and practically everything made by Roman Polanski. It is also very strong in German cinema.

In short, what Buñuel innocently began has become possibly the most important influence in genre cinema after the German Gothic. Sometimes the influence is direct, sometimes it is because of the language of surrealism has become part of the way we think, now familiar to billions who have never even heard of Buñuel. Following L’Âge d’Or, Buñuel returned to Spain and directed Las Hurdes Tierra Sin Pan (1933), a documentary on peasant life in Extremadura, one of the poorest states in Spain. This was a convulsive period which led, in 1936, to the Spanish Civil War. The times were changing quickly and Buñuel could see that someone with his political and artistic sensibilities would have no place in a fascist Spain. He co-wrote and produced a documentary short about the changing political climes in Spain, called España (1936). The advent of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 caused the expatriation of many artists and intellectuals from the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco, whose military revolt and rise to power had had the strong backing of the Spaniard Catholic hierarchy. Had Buñuel stayed in Spain, his fate might have been the same as that of his friend, poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who was assassinated at the outset of Franco’s military revolt.

In short, what Buñuel innocently began has become possibly the most important influence in genre cinema after the German Gothic. Sometimes the influence is direct, sometimes it is because of the language of surrealism has become part of the way we think, now familiar to billions who have never even heard of Buñuel. Following L’Âge d’Or, Buñuel returned to Spain and directed Las Hurdes Tierra Sin Pan (1933), a documentary on peasant life in Extremadura, one of the poorest states in Spain. This was a convulsive period which led, in 1936, to the Spanish Civil War. The times were changing quickly and Buñuel could see that someone with his political and artistic sensibilities would have no place in a fascist Spain. He co-wrote and produced a documentary short about the changing political climes in Spain, called España (1936). The advent of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 caused the expatriation of many artists and intellectuals from the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco, whose military revolt and rise to power had had the strong backing of the Spaniard Catholic hierarchy. Had Buñuel stayed in Spain, his fate might have been the same as that of his friend, poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who was assassinated at the outset of Franco’s military revolt.

There has always been in surrealism a strong element of shocking the bourgeois. Conversely, those who want to put sacred cows through the meat-grinder are likely to choose surrealist devices to do so. Surrealism is well-adapted to puncturing pomposity and lampooning bombast. It is almost too well-adapted, because its devices can be used rather mechanically – a surrealist film is not necessarily an imaginative one. Surrealism thrives on the escalation of small disturbing incidents into full-bodied chaos. Most of us, in part of our minds, rather like the idea of seeing society blown magnificently apart. Half the fun of building a sand castle is, once it is complete and frozen, seeing the tide come in and wash it away. Real society, of course, is not a sand castle, but the impulse remains, though it is naturally repressed in polite circles. It is this same impulse that has led to the ongoing tradition of anarchic surrealist satire, sometimes comic, sometimes not, that has characterised genre cinema for the last half-century.

There has always been in surrealism a strong element of shocking the bourgeois. Conversely, those who want to put sacred cows through the meat-grinder are likely to choose surrealist devices to do so. Surrealism is well-adapted to puncturing pomposity and lampooning bombast. It is almost too well-adapted, because its devices can be used rather mechanically – a surrealist film is not necessarily an imaginative one. Surrealism thrives on the escalation of small disturbing incidents into full-bodied chaos. Most of us, in part of our minds, rather like the idea of seeing society blown magnificently apart. Half the fun of building a sand castle is, once it is complete and frozen, seeing the tide come in and wash it away. Real society, of course, is not a sand castle, but the impulse remains, though it is naturally repressed in polite circles. It is this same impulse that has led to the ongoing tradition of anarchic surrealist satire, sometimes comic, sometimes not, that has characterised genre cinema for the last half-century.

The master of this kind of film was the late Buñuel, who was permitted, even encouraged by middle-class society all over the world, to play anarchic games. Perhaps this was because so long as they could be perceived as games, they were distanced and non-threatening. Thus arose his slightly ambiguous position over the last decades of his life (he passed away in 1983), as licensed jester to the courts of the bourgeoisie.

The master of this kind of film was the late Buñuel, who was permitted, even encouraged by middle-class society all over the world, to play anarchic games. Perhaps this was because so long as they could be perceived as games, they were distanced and non-threatening. Thus arose his slightly ambiguous position over the last decades of his life (he passed away in 1983), as licensed jester to the courts of the bourgeoisie.

The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (1972) makes the point immediately in its ironic and not untruthful title: Guests arrive for dinner on the wrong evening, so they are taken to a restaurant, but a funeral is about to take place there. The following day the guests arrive again, but their hosts have capitulated to uncontrollable erotic urges and are coupling in the garden, then a bishop arrives to ask for the post of gardener and, after initial doubts, he is hired. A young soldier tells a ghost story in a tea-room (it’s quite a bloody tale, we see it ourselves). An adulterous assignation between two of the earlier dinner guests is interrupted, and a third attempt at a dinner party is foiled by the arrival of billeted troops when their sergeant tells another ghost story. The fourth attempt at dinner is a dream sequence where the poultry is made of plaster and a curtain rises to reveal that the table is on the stage of a theatre. The bishop hears a confession, absolves the sinner then shoots him, and soon after another ghost story is told. At the fifth attempt at dinner terrorists enter and shoot the guests. So far nobody in the film has managed to eat anything at all. A guest reveals himself by reaching up to take some meat from a plate from beneath the table where he had crawled. He is shot. Waking up from his nightmare, he goes to the refrigerator for a snack.

The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (1972) makes the point immediately in its ironic and not untruthful title: Guests arrive for dinner on the wrong evening, so they are taken to a restaurant, but a funeral is about to take place there. The following day the guests arrive again, but their hosts have capitulated to uncontrollable erotic urges and are coupling in the garden, then a bishop arrives to ask for the post of gardener and, after initial doubts, he is hired. A young soldier tells a ghost story in a tea-room (it’s quite a bloody tale, we see it ourselves). An adulterous assignation between two of the earlier dinner guests is interrupted, and a third attempt at a dinner party is foiled by the arrival of billeted troops when their sergeant tells another ghost story. The fourth attempt at dinner is a dream sequence where the poultry is made of plaster and a curtain rises to reveal that the table is on the stage of a theatre. The bishop hears a confession, absolves the sinner then shoots him, and soon after another ghost story is told. At the fifth attempt at dinner terrorists enter and shoot the guests. So far nobody in the film has managed to eat anything at all. A guest reveals himself by reaching up to take some meat from a plate from beneath the table where he had crawled. He is shot. Waking up from his nightmare, he goes to the refrigerator for a snack.

These crazy juxtapositions, where violence and death continually intrude on a group of elegant gourmets whose lives are only minimally disturbed by these events, are created with calm panache. Society is corrupt but unflappable. At all levels it requires the satisfaction of appetites for food and sex. The world of gentility and the world of horror do indeed collide, but somehow the impact is muffled. Perhaps one of these worlds is a dream, but which one?

These crazy juxtapositions, where violence and death continually intrude on a group of elegant gourmets whose lives are only minimally disturbed by these events, are created with calm panache. Society is corrupt but unflappable. At all levels it requires the satisfaction of appetites for food and sex. The world of gentility and the world of horror do indeed collide, but somehow the impact is muffled. Perhaps one of these worlds is a dream, but which one?

The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie is a model of linear narration compared to the spiraling contorted structure of Buñuel’s next film The Phantom Of Liberty (1974). Unlike the previous film, this does actually end in social apocalypse as an open revolt breaks out at the zoo, observed by a curious ostrich that fails to bury its head in the sand, unlike another ostrich that appears in a man’s bedroom earlier on. The film consists of a series of unfinished stories, a minor character in one becoming the protagonist in the next, not unlike the format adopted by David Lynch in such films as Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001). They are tall stories, the kind that get an immediate easy laugh, and then when they sink in, a more difficult choked laugh. In one story a doctor offers a patient, who has just been told he’s suffering from terminal lung cancer, a consolatory cigarette. In another story, distraught parents search for their missing daughter who is, in fact, there all the time but cannot attract their attention to let them know. A pervert gives dirty postcards to children in the park, the shocked parents confiscate them and then become exited themselves by what they show – the postcards are revealed to be simple landscapes. A police inspector is telephoned by his dead sister then, after rushing to the family crypt, he finds that the phone is off the hook. At a dinner party, the guests sit around the table on toilet bowls into which they occasionally relieve themselves, conversation is sophisticated and unconcerned, but every now and then one excuses himself and goes off to a private cabinet to eat.

The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie is a model of linear narration compared to the spiraling contorted structure of Buñuel’s next film The Phantom Of Liberty (1974). Unlike the previous film, this does actually end in social apocalypse as an open revolt breaks out at the zoo, observed by a curious ostrich that fails to bury its head in the sand, unlike another ostrich that appears in a man’s bedroom earlier on. The film consists of a series of unfinished stories, a minor character in one becoming the protagonist in the next, not unlike the format adopted by David Lynch in such films as Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001). They are tall stories, the kind that get an immediate easy laugh, and then when they sink in, a more difficult choked laugh. In one story a doctor offers a patient, who has just been told he’s suffering from terminal lung cancer, a consolatory cigarette. In another story, distraught parents search for their missing daughter who is, in fact, there all the time but cannot attract their attention to let them know. A pervert gives dirty postcards to children in the park, the shocked parents confiscate them and then become exited themselves by what they show – the postcards are revealed to be simple landscapes. A police inspector is telephoned by his dead sister then, after rushing to the family crypt, he finds that the phone is off the hook. At a dinner party, the guests sit around the table on toilet bowls into which they occasionally relieve themselves, conversation is sophisticated and unconcerned, but every now and then one excuses himself and goes off to a private cabinet to eat.

Social surfaces are more important than the realities that lie beneath. Not too far beneath the surface of the film, characters are half in love with death. A mad rooftop sniper becomes a popular hero and, at the film’s opening, an execution scene parodies a Goya painting of the same subject, Buñuel himself has a walk-on part as a man patiently waiting to be shot. The film ends in gunfire. The surrealist disjunctions of The Phantom Of Liberty point in a darker direction than those in The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (as does its title), which may be why this superficially affable and jokey film never had quite the popular success of its predecessor – it is quite possibly Buñuel’s masterpiece of masterpieces. Please join me next week on Horror News when I have the opportunity of inflicting a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

Social surfaces are more important than the realities that lie beneath. Not too far beneath the surface of the film, characters are half in love with death. A mad rooftop sniper becomes a popular hero and, at the film’s opening, an execution scene parodies a Goya painting of the same subject, Buñuel himself has a walk-on part as a man patiently waiting to be shot. The film ends in gunfire. The surrealist disjunctions of The Phantom Of Liberty point in a darker direction than those in The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (as does its title), which may be why this superficially affable and jokey film never had quite the popular success of its predecessor – it is quite possibly Buñuel’s masterpiece of masterpieces. Please join me next week on Horror News when I have the opportunity of inflicting a pain beyond pain, an agony so intense it shocks the mind into instant mashed potato! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews