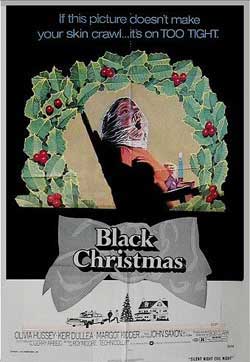

The mysterious maniac in director Bob (Deathdream) Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) has no redeeming values. Unlike so many morality-lesson-driven Yuletide tales, Black Christmas’ madman, Billy the Killer, finds no redemption at the end. He remains a vile and evil murderer whose deranged psychosis drives him to taunt and kill. The ambiguous ending hints the killer receives no just punishment, either. He’s free to kill and kill again.

Black Christmas’ holiday setting adds further eeriness to the downbeat tale. Billy’’s homicidal rampage delivers more emotional impact because the events play out at a time known for cheer and festivities. The murderous psycho is so out of place in a Christmas setting that the events become even more unnerving.

But is Billy the Killer truly out of place in a Christmas film? Christmas could be an unhappy holiday for someone who opens a stocking to find coal. Other bad things, worse things, could happen at Christmas for the so-called “naughty.”

Not the First Noel, a Fatal and Final One

Black Christmas certainly is not the first “slasher” film ever made, but many influential tropes later found in Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), and their progeny come from the 1974 chiller. An underlying theme found in the 1980s slasher film craze focused on how the victims’ “immorality” led to their fates. Many teens die after having premarital sex, abusing alcohol or drugs, or doing “outright stupid things,” such as taking a bath two minutes after someone in a house gets murdered.

Clark’s film stays rooted in reality and never suffers from unintentional self-parody. Punishment for bad deeds drivers Billy, but in an understated, subtle, and terrifying way. Billy might not consciously slaughter teenagers as an attempt to impose moral judgment. Still, he meets out punishment based on his perceptions about how people should behave.

Black Christmas remains rooted in reality or presents proceedings as plausible as a killer-in-the-sorority-house attic can become. Several killings are chillingly realistic, and the idea a killer could hide in an attic for a few hours isn’t too implausible. Within the added realism comes the realism of slasher-morality killings. Barb behaves obnoxiously and drinks to excess while Jess struggles with the consequences of premarital sex. The house mother, Mrs. MacHenry, appears self-absorbed and detached from her job, and tortured musician Peter doesn’t know what he wants in life and doesn’t see Jess as an independent person. Poor Clare, she’s merely naive.

The 1980s concept that “bad behavior” leads to death appeared to give audiences a cop-out. They could point to the victims’ “flaws” as a deflection from watching make-believe murders play out on screen. In Black Christmas takes a more intellectual, restrained approach, giving audiences no reprieve.

The victims’ behavior doesn’t devolve into the buffoonish, as seen in many lame slasher films. The “bad” behavior is, truthfully, normal human behavior. But it doesn’t meet Billy’s standards of acceptability.

Billy the Killer ironically sees himself as the arbitrator of morality, and he spews vulgarities at “wayward girls” through making obscene phone calls. He’s oblivious to his own psychological problems, nor does he see the unbearable wrongness of his behaviors. He’s so self-righteous and misogynistic that he views his punishment-driven murders as justified while ignoring his outrageous lack of morality.

So he’s delivering coal for Christmas in his homicidal, psychotic way.

Leaving Coal and Death

As everyone knows, “bad” children may receive a lump of coal for Christmas. Undeserved of toys or candies, the naughty get a seemingly useless and insulting stocking of sedimentary rock. While no kid would want coal for Christmas, coal did keep many of them alive during the harsh winters if they relied on a coal-burning furnace in centuries past.

Like socks and savings bonds, coal might lack the cool factor associated with toys, but coal furnaces kept people from freezing to death in generations past. In the 19th Century, a stocking filled with coal might fall under the “You can’t always get what you want…You get what you need” banner.

Fear would drive children’s behavior, including the fear of disappointment or embarrassment of receiving a stocking of coal on what should be a child’s most joyful day. So, children presumably alter their behavior to avoid a psychological punishment.

The killer in Black Christmas reflects a stocking full of coal coming to homicidal life. More tellingly, Billy represents another wing of the abusive symbolism associated with receiving coal. Coal reflects psychological punishment through a physical “gift.” The killer delivers the ultimate physical punishment, death, to those he believes are “bad.” Murder follows when psychological torment – obscene phone calls – fails to deliver the desired behavioral response.

The fictional killer represents a melodramatic version of many real-life sociopaths. He kills based on psychological derangement and a desire to punish those who fail to live up to his moral lines in the snow. Toe the arbitrary line or receive coal, children. Don’t cross a moral and behavioral line, college girls and boys, or face the mortal consequences.

In the Bleak Mid-Winter of Fear

No argument for a sane comparison between the cruel prank of a stocking full of coal to a senseless murder spree exists. Black Christmas doesn’t reflect actual events, nor is the mysterious murderer a real-life serial killer. The film and its antagonist draw inspiration from the notorious urban legend about the “Babysitter and the Man Upstairs,” a paranoid story about a babysitter taunted by creepy phone calls, contacts the police who then trace the line, discovering the calls are coming from inside the house.

The urban legend attempts to warn people – through fear – to be alert to danger in any environment or suffer the consequences. Failing to take an obscene phone caller’s threats about killing people seriously results in not being on guard and facing death.

Blaming the victims for their demise seems appalling. Yet, that seems to be the message in many urban legends, and it carries over to Black Christmas. The film’s characters have human flaws and human problems. A. Roy Moore’s screenplay understandably heightens the melodrama in the dialogue. He’s crafting a horror potboiler, not a true-life drama.

The characters may speak and act a bit melodramatic, seen in the somewhat stilted dialogue between troubled lovers Peter and Jess. In over-the-top horror-film fashion, their troubles draw unwanted attention from Billy, who delivers a morality-based punishment.

Are Peter and Jess’ troubles abnormal? No, they represent not uncommon relationship struggles then and now. Is Peter’s sexist, controlling attitude appropriate? No, but he never takes deliberate steps to harm Jess, although his patriarchal demeanor borders on threatening. Is their relationship struggles anyone’s business? No, but Billy the Killer remains the center of the moral universe in his twisted mind.

And what does it sincerely mean to be “naughty?” As with “immoral,” the term could be ambiguous. Stealing from the indigent is universally immoral. Millions of fans enjoy watching horror movies, a pastime some may feel is immoral. The former action reflects criminality while the latter is opinion. The trouble is that some people take their opinions and use them to impose punishment.

Some won’t take Christmas off from their joy of meeting out punishment, as seen in centuries of coal-filled stockings. And also seen in the homicidal rampage of the Christmas horror grinch, Billy the Killer.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews