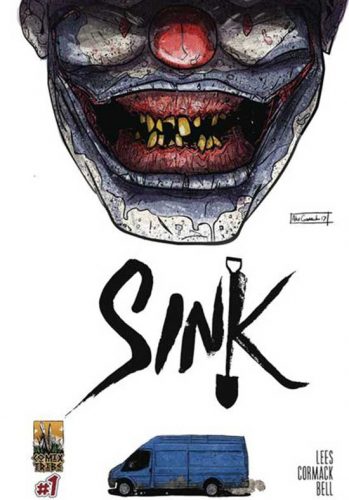

WRITTEN BY JOHN LEES

ART & COLOURS BY ALEX CORMACK

LETTERS BY COLIN BELL

PUBLISHED BY COMIX TRIBE

The horror genre is known for its ubiquitous settings; a haunted family home, a house full of inbreeds in the middle of nowhere or a graveyard teeming with the undead. But horror fans are a fairly twisted bunch, and as much as we love these familiar backdrops, what we really crave is the thrill of being thrust into the middle of somewhere unexpected. How does a housing estate in Glasgow, Scotland sound?

Written by John Lees (And Then Emily was Gone), with art and colours by Alex Cormack (Oxymoron) Sink is named after a sink estate, urban parts of the UK known for economic and social deprivation, and in many cases, crime. The book opens in more comfortable surroundings as we meet Allan in a nightclub, bragging to friends about the cultural superiority of his city, while asserting himself as a product of its gritty reputation. It’s clear Allan is from the safer side of the tracks, and little of what he says is spoken from real experience. After missing the last bus and failing to find a cab, Allan is forced to walk home alone.

It’s at this point that the city he’s just been boasting about turns on him, as his walk home takes him through Sinkhill, the estate inferred in the title. Very quickly he meets a succession of late night weirdo’s brandishing everything from knives to condoms used as hats, and it’s here that this comic goes from gloriously unsettling to downright nerve shredding. Allan is stalked by even more stab happy, condom clad crazies and almost certainly doomed, until Mr. Dig – a fox-masked, shovel wielding anti-hero you’ll be praying gets an action figure – turns up to save him.

It’s clear Lees understands the city and character types he is writing about. Their voices are distinct, believable and ominously familiar. There is an element of class satire here, but it’s allowed to be a horror story first and foremost. The world of Sink feels like it’s been alive long before the opening page, hinting at its own folklore and then delivering on it just when you think poor Allan has come out the other side. Cormack’s art is first class. Each character is imbued with the right emotion from panel to panel, and rendered with a subtlety you don’t often see in horror comics. His colouring too is exceptional, with a texture that feels like you’re looking into the darkness, praying that whatever you think you see up ahead isn’t really there. Any good horror story succeeds or fails based on its ability to put the audience in the middle of the nightmare; to wonder what you might do if you found yourself being run down by a sadistic crackpot. And it’s that sense of realism that makes this book so horrific. We’ve all been in Allan’s situation, walking home drunk, feeling vulnerable on unexplored streets, hoping we don’t wind up as a segment on tomorrow night’s news.

’There are worse things on the streets than dickheads’ says Mr. Dig, and to elaborate on what happens once he makes his presence felt would be cruel. But if you enjoy stories where things go from bad to unfathomably worse, Sink is the horror comic you need. And while it works perfectly as a stand-alone story, it doesn’t end here. This is the start of what promises to be one of the best ongoing horror books in recent years.

This first issue is a slow burn, expertly constructed so that the fear creeps up on you page by page, until the final panels quite literally come at you head on. You might be advised to devour this on a monthly basis as the genuine sense of terror that came from reading it was as surprising as it was a dark, vicarious pleasure. Just don’t read it on the walk home.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews