SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“A serial killer known as the Avenger is murdering blonde women in London. A new lodger, Jonathan Drew, arrives at Mr. and Mrs. Bounting’s in Bloomsbury and rents a room. The man has some strange habits, he goes out during foggy nights and keeps a picture of a blonde girl in his bedroom. The Bounting’s daughter, Daisy, is a blonde model and she is engaged to Joe, a detective. When Joe finds out that Bounting suspects Jonathan, he is jealous of the lodger flirting with Daisy and arrests the man accusing him of being the Avenger.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Alfred Hitchcock began his film career in 1920 as a designer of silent film title cards, soon becoming art director, scriptwriter, and director. After nine silent films he directed the first British sound film, Blackmail (1929), followed by a number of superb thrillers: The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The Thirty-Nine Steps (1934), Young Innocent (1937) and The Lady Vanishes (1938). He was then invited to America by producer David O. Selznick to make Rebecca (1940) and the rest, as they say, is history. This week I wish to discuss the third film directed by Hitchcock during the silent era and the first in the genre with which he would forevermore be associated – the suspense thriller.

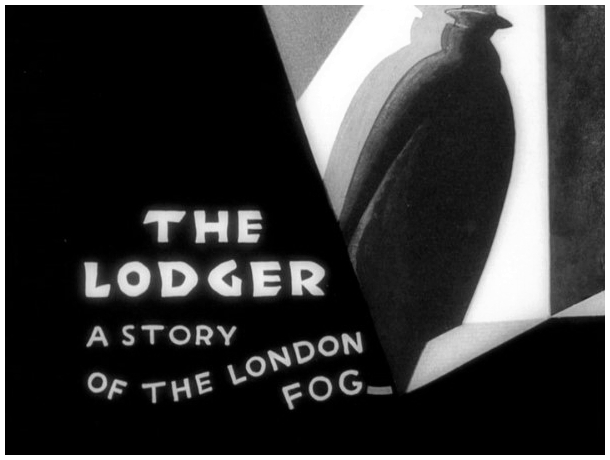

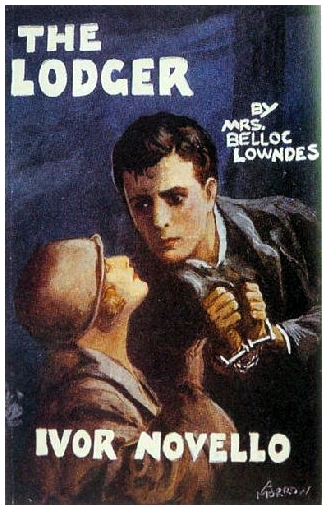

The Lodger (1927) subtitled A Story Of The London Fog was adapted by Eliot Stannard from a rather brilliant novel by Marie Belloc-Lowndes with a ‘Jack The Ripper’ theme, in which an unknown murderer is at large eliminating blondes. To a Bloomsbury boarding house comes a mysterious young man who keeps to himself and paces the floor despairingly before gliding out of the house on nocturnal sorties. Inevitably he is suspected, arrested and almost lynched before his innocence is established by the red-handed capture of the real killer. A major figure from the West End stage was cast in the lead, the popular Ivan Novello. The fact that he was a matinee idol meant that he had to be found innocent by the end, much to Hitchcock’s disappointment, for he would have preferred to have left open the possibility that he was the murderer. The same problem would crop up years later when Cary Grant behaved like a murderer in Suspicion (1941).

Nevertheless, The Lodger vividly demonstrates some recurring Hitchcock themes: Circumstantial evidence placing an innocent man in serious jeopardy; the hysterical unreason of mob mentality; the use of handcuffs, presaging The Thirty Nine Steps (1935), Saboteur (1942) and The Wrong Man (1956). It was also the first film in which Hitchcock made a small appearance – in fact he can be spotted twice in The Lodger, the first in a newspaper office, the second amongst the crowd witnessing the arrest of Novello. Appearing originally because there was a need to swell the number of extras in the crowd, Hitchcock later adopted these token glimpses as a sort of signature, not only as a superstition but also as a means of exercising his ingenuity in such sparsely-populated films as Lifeboat (1944) and Rope (1948).

Nevertheless, The Lodger vividly demonstrates some recurring Hitchcock themes: Circumstantial evidence placing an innocent man in serious jeopardy; the hysterical unreason of mob mentality; the use of handcuffs, presaging The Thirty Nine Steps (1935), Saboteur (1942) and The Wrong Man (1956). It was also the first film in which Hitchcock made a small appearance – in fact he can be spotted twice in The Lodger, the first in a newspaper office, the second amongst the crowd witnessing the arrest of Novello. Appearing originally because there was a need to swell the number of extras in the crowd, Hitchcock later adopted these token glimpses as a sort of signature, not only as a superstition but also as a means of exercising his ingenuity in such sparsely-populated films as Lifeboat (1944) and Rope (1948).

When filming of The Lodger was completed it was edited by film critic Ivor Montagu (it’s astonishing by today’s standards how various specialised functions in film-making were tossed around during the flexible twenties), and artist Edward McKnight Kauffer designed the beautiful art-deco titles, which had also been written with considerable economy by Montagu. The distributors then sat through a preview of the film, decided it was too heavy in treatment, too obscure in plot, too gloomy to do anything at the box-office, and shelved it accordingly. Some months later it was decided to risk releasing it, and The Lodger was instantly acclaimed as one of the best British films ever made and was a huge success with critics and public alike. Hitchcock’s reputation was established at the age of twenty-seven.

When filming of The Lodger was completed it was edited by film critic Ivor Montagu (it’s astonishing by today’s standards how various specialised functions in film-making were tossed around during the flexible twenties), and artist Edward McKnight Kauffer designed the beautiful art-deco titles, which had also been written with considerable economy by Montagu. The distributors then sat through a preview of the film, decided it was too heavy in treatment, too obscure in plot, too gloomy to do anything at the box-office, and shelved it accordingly. Some months later it was decided to risk releasing it, and The Lodger was instantly acclaimed as one of the best British films ever made and was a huge success with critics and public alike. Hitchcock’s reputation was established at the age of twenty-seven.

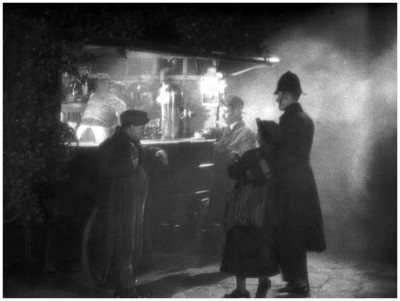

The film is rich in visual effects that portended the extent of Hitchcock’s cinematic imagination. One of the most famous was the glass ceiling, whereby the man pacing in his room upstairs became visible from the room below. Another was the opening scene in which the murder victim faces the camera and screams: Hitchcock filmed the scene by having the actress lie down on a large sheet of glass with her golden hair spread out around her head. He then lit the actress from underneath and filmed her with a camera mounted on its side, with the lens pointed at a downward angle. This gave the appearance that the actress’s blonde hair (so important to the murderer) was ringed in a halo of light. Such devices were necessary in silent cinema, but sound made it possible to convey information much more succinctly.

The film is rich in visual effects that portended the extent of Hitchcock’s cinematic imagination. One of the most famous was the glass ceiling, whereby the man pacing in his room upstairs became visible from the room below. Another was the opening scene in which the murder victim faces the camera and screams: Hitchcock filmed the scene by having the actress lie down on a large sheet of glass with her golden hair spread out around her head. He then lit the actress from underneath and filmed her with a camera mounted on its side, with the lens pointed at a downward angle. This gave the appearance that the actress’s blonde hair (so important to the murderer) was ringed in a halo of light. Such devices were necessary in silent cinema, but sound made it possible to convey information much more succinctly.

In one particular scene Hitchcock wanted to show the first murder victim being dragged out of the Thames River at night with the Charing Cross Bridge in the background, but Scotland Yard refused his request to film at the bridge. Hitchcock repeated his request several times, until Scotland Yard said they would ‘look the other way’ if he could do the filming in one night. So, in what might be the very first case of guerrilla film-making, Hitchcock quickly sent his cameras and actors out to Charing Cross Bridge to film the scene, but when the rushes came back from the developers, the scene at the bridge was nowhere to be found. Hitchcock and his assistants searched through the prints, but couldn’t find it. Finally, he discovered that his cameraman had simply forgotten to put the lens on the camera before filming.

Ridiculous mistakes like this fueled Hitchcock’s drive for professionalism, care and precision, giving his films a distinctive polish. His pre-production capacity is legendary: Before a single frame of film is exposed, he would read the script repeatedly, rejecting and rewriting, he would never improvise on-set, his actors rehearsed their roles to perfection, his cinematographer knew exactly what was required, he had no need to look through the viewfinder. When asked about his film-making methods, he would simply state, “My films are made on paper.” With that thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews