SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Young traveller Allan Grey arrives in a remote castle and starts seeing weird, inexplicable sights (a man whose shadow has a life of its own, a mysterious scythe-bearing figure tolling a bell, a terrifying dream of his own burial). Things come to a head when one of the daughters of the lord of the castle succumbs to anaemia – or is it something more sinister?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

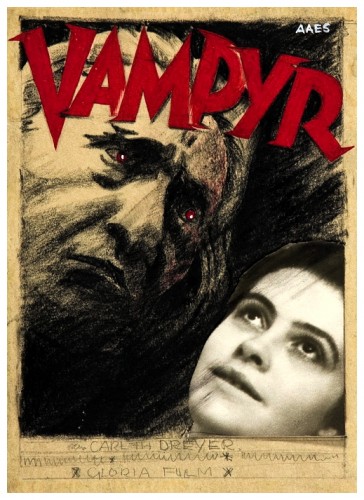

What filmmaker Luis Buñuel innocently began in the twenties with Surrealism has probably become the most important influence in genre cinema after the German Gothic. Sometimes the influence is direct, sometimes it’s because the language of surrealism has become part of the way we think, now familiar to billions of people who have never even heard of Buñuel or his contemporaries. Curiously enough, one of the most obviously surrealist films of the thirties had no direct link with the surrealist movement, though its director was probably aware of its existence. I’m talking about Carl Dreyer and his moody masterpiece Vampyr (1932), which is unlike any other vampire film ever made, before or since.

It’s not so much a horror film as an eerie mood piece, a dream, the visualisation of the conflict between the heart and the brain for the soul. Critic William K. Everson once described Vampyr as, “The one undisputed masterpiece of the genre” and, somewhat hesitantly, I do not dispute this. The hesitation is because most of the available prints are of poor quality, and it’s difficult to tell to what extent their washed out appearance is the fading due to generations of reduplication, and to what extent it is the deliberate bleached look Carl Dreyer gave to the film. The compelling cinematography is the work of Rudolph Maté, who later moved to Hollywood to direct such semi-classics as D.O.A. (1950) and When Worlds Collide (1951), and deserves just as much credit as Dreyer for this monumental work.

It’s not so much a horror film as an eerie mood piece, a dream, the visualisation of the conflict between the heart and the brain for the soul. Critic William K. Everson once described Vampyr as, “The one undisputed masterpiece of the genre” and, somewhat hesitantly, I do not dispute this. The hesitation is because most of the available prints are of poor quality, and it’s difficult to tell to what extent their washed out appearance is the fading due to generations of reduplication, and to what extent it is the deliberate bleached look Carl Dreyer gave to the film. The compelling cinematography is the work of Rudolph Maté, who later moved to Hollywood to direct such semi-classics as D.O.A. (1950) and When Worlds Collide (1951), and deserves just as much credit as Dreyer for this monumental work.

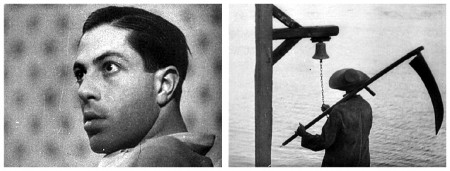

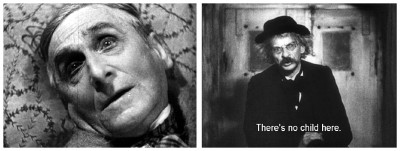

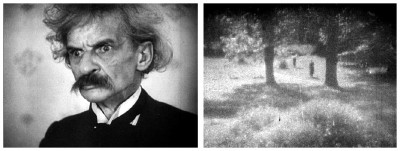

Allan Gray (Nicolas de Gunzburg) is an investigator of the supernatural whose journeys take him to the village of Courtenpierre. He finds that sisters Leone (Sybille Schmitz) and Gisele (Rena Mandel) are being threatened by a vampire witch (Henriette Gerard) and her evil human colleagues, a doctor (Jan Hieronimko) and a peg-legged gamekeeper (Albert Bras). Leone is already deathly ill and shows signs of turning into a vampire. Most vampire films – indeed most horror films – deal with the conflict between good and evil, but Dreyer links his vampires with Satan and makes Courtenpierre a religious battleground where believers and blasphemers wage war. Survivors Allan and Gisele are allowed to leave at the end and venture into a heavenly forest.

Vampyr is based rather remotely on Sheridan Le Fanu‘s classic story Carmilla about a female vampire. It has little direct terror, but a suffocating claustrophobic sense of the unnatural pervades it. The film has a slow inexorable dreamlike quality that immediately suggests its strong relationship to surrealism, as does its emphasis on inexplicable events: a policeman’s shadow walks off without him; a peasant waiting for a ferry looks like Death holding his scythe; the hero dreams of being buried alive (the camera stares point-of-view through the coffin’s window as it is carried to the graveyard); the vampire is actually a withered old woman; an old man enters the hero’s bedroom at night and whispers, “She must not die.” The evil doctor is finally trapped mysteriously in a cage in a flour mill and suffocated with the fine white powder that bleaches the screen completely, recapitulating the strange pallor of all the previous events.

Vampyr is based rather remotely on Sheridan Le Fanu‘s classic story Carmilla about a female vampire. It has little direct terror, but a suffocating claustrophobic sense of the unnatural pervades it. The film has a slow inexorable dreamlike quality that immediately suggests its strong relationship to surrealism, as does its emphasis on inexplicable events: a policeman’s shadow walks off without him; a peasant waiting for a ferry looks like Death holding his scythe; the hero dreams of being buried alive (the camera stares point-of-view through the coffin’s window as it is carried to the graveyard); the vampire is actually a withered old woman; an old man enters the hero’s bedroom at night and whispers, “She must not die.” The evil doctor is finally trapped mysteriously in a cage in a flour mill and suffocated with the fine white powder that bleaches the screen completely, recapitulating the strange pallor of all the previous events.

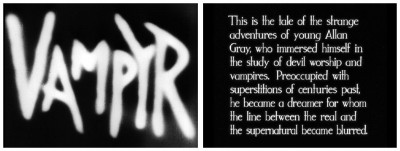

The words of the prologue prepare us for this very dreamlike quality: “There exist certain beings whose very lives seem bound by invisible chains to the supernatural. They crave solitude. To be alone and dream – their imagination is so developed that their vision reaches beyond that of most men.” Thus the almost somnambulistic, curiously passive hero is not the innocent observer who walks into most vampire films. It is as if his very personality creates the fantastic horrors that entrap him. Of these, the most terrifying touch is the most subtle. In one particular scene that would be often imitated but rarely well, Leone, who has been bitten by a vampire, lies in bed looking tortured and weak. She slowly turns her head and, as she does so, her expression changes from innocence to sexual malignance as she passes her tongue across her teeth. No fangs, no special effects, but a disturbing moment nonetheless.

The words of the prologue prepare us for this very dreamlike quality: “There exist certain beings whose very lives seem bound by invisible chains to the supernatural. They crave solitude. To be alone and dream – their imagination is so developed that their vision reaches beyond that of most men.” Thus the almost somnambulistic, curiously passive hero is not the innocent observer who walks into most vampire films. It is as if his very personality creates the fantastic horrors that entrap him. Of these, the most terrifying touch is the most subtle. In one particular scene that would be often imitated but rarely well, Leone, who has been bitten by a vampire, lies in bed looking tortured and weak. She slowly turns her head and, as she does so, her expression changes from innocence to sexual malignance as she passes her tongue across her teeth. No fangs, no special effects, but a disturbing moment nonetheless.

Admittedly, the movie is leisurely-paced and has no shocks, but I’m sure even younger horror movie fans will be able to recognise why it is so well-regarded. Filmed as if it was a silent film, it contains several startling visual passages, and the entire film has an effectively haunting, misty look due to the use of gauze over the camera’s lens. Here then is another of the great focal points of horror cinema, the film which established so brilliantly the link between the fantasies of the mind and the way in which external reality is seen. The whole film exists in the half-light of dawn and dusk, in a never-never world of quietness and mist. I sincerely hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation but, then again, I sincerely hope for world peace and a Ferrari. Nevertheless, since you’re still reading this, I’m sure I can count on having your company again when I pick another forgotten fragment of filmic fluff from cinema’s lint trap next week for…Horror News! Toodles!

Admittedly, the movie is leisurely-paced and has no shocks, but I’m sure even younger horror movie fans will be able to recognise why it is so well-regarded. Filmed as if it was a silent film, it contains several startling visual passages, and the entire film has an effectively haunting, misty look due to the use of gauze over the camera’s lens. Here then is another of the great focal points of horror cinema, the film which established so brilliantly the link between the fantasies of the mind and the way in which external reality is seen. The whole film exists in the half-light of dawn and dusk, in a never-never world of quietness and mist. I sincerely hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation but, then again, I sincerely hope for world peace and a Ferrari. Nevertheless, since you’re still reading this, I’m sure I can count on having your company again when I pick another forgotten fragment of filmic fluff from cinema’s lint trap next week for…Horror News! Toodles!

Vampyr (1932)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews