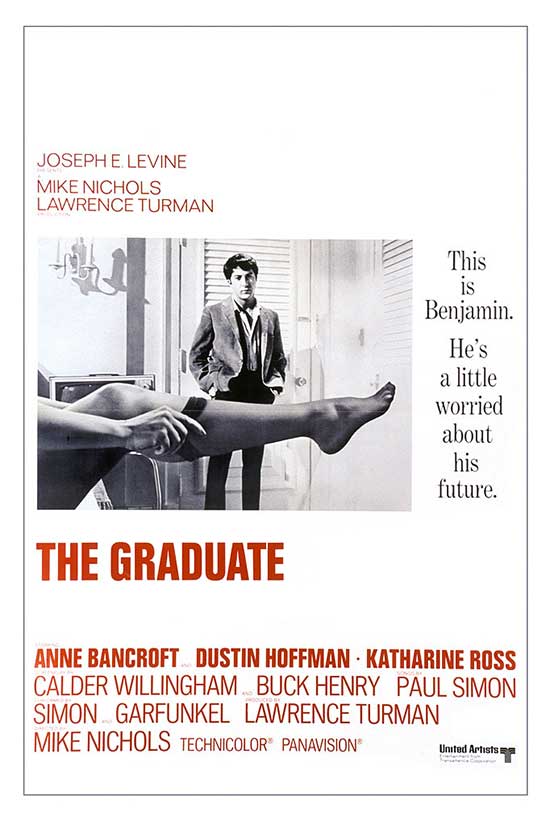

Simon and Garfunkel’s song “The Sound of Silence,” with the unforgettable lyrics, “Hello, darkness my old friend,” contributes to the brilliance of the opening credit sequence of The Graduate (1967). The song would be a perfect fit for the dark, depressing “Return home from Vietnam” drama/undead horror classic Deathdream (1974).

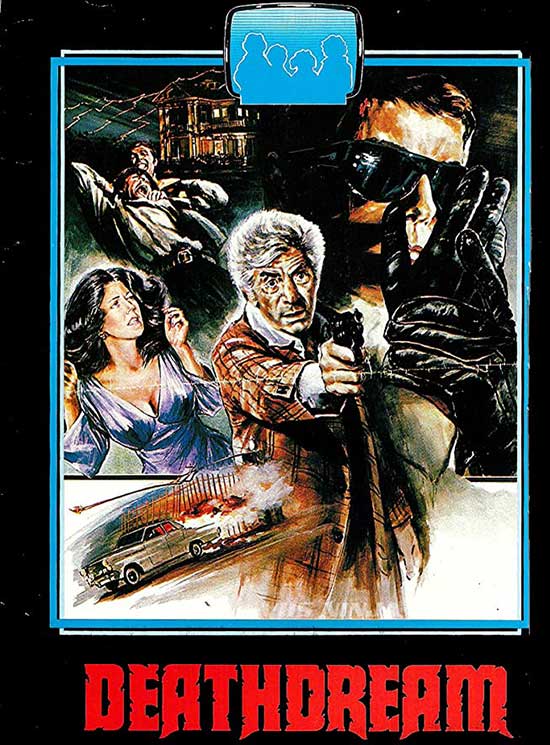

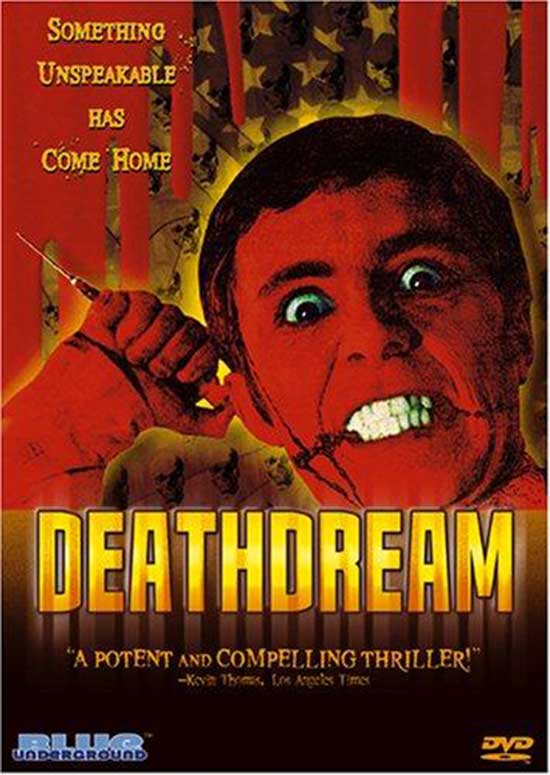

Deathdream didn’t score the same box office success as The Graduate, but the exceptional film maintains and grows a cult following. Masterfully written by Alan Ormsby and directed by Bob Clark, the team previously scored an ultra-low-budget zombie hit with Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972). Deathdream did not play in many U.S. theaters outside of a few bookings in the south, but the film became a late 1970s/early 1980s UHF hit where the modern-day, full-color horror opus chilled viewers’ nerves.

In Deathdream, a mother wishes her son, Andy, would return home from Vietnam, and she doesn’t believe the notification he died. Her wishes come true, and a withdrawn, silent, frightening Andy does return. While the family blames psychological trauma for his behavior, there’s a more ominous reason why he’s so strange: Andy’s become one of the living dead and requires blood to keep from turning into a rotting corpse.

How on earth does a low-budget, drive-in horror film share similarities with The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman’s career-making mega-hit, one tapping into a cultural nerve when first released? The Graduate dealt with an aimless recent college graduate, Benjamin Braddock, who knows he’s going nowhere in life, so he accepts his listless moping and meandering into the “real world.” Benjamin awakens out of his boring slumber after having an affair with a married woman, the eternal Mrs. Robinson.

One of Deathdream’s alternate title, The Night Andy Came Home, shares some connections with The Graduate, as director Mike Nichols’ film also deals with a young man’s return home and the subsequent chaotic result. Looking beyond that surface-level connection reveals additional thematic similarities.

Coming Home: Dead and/or Alive

Both features make a motif out of a young person’s arrival. In The Graduate, the film opens with Benjamin traveling by plane. The look on Benjamin’s face shows him to near-catatonic, lost in deep internal thoughts. He is almost zombie-like as he goes through the airport by himself, interacting with no one.

Similarly, Andy travels home by hitchhiking. A friendly truck driver picks him up, but Andy sits in silence and has no interactions with a man. The truck driver even refers to Andy as being “weird” at a local diner. Andy exudes a homicidal, detached menace. He’s coming home, but he doesn’t belong there. And Andy’s not alone.

Is Dustin Hoffman’s Benjamin Braddock character much different than Deathdream’s Andy Brooks? Yes, they differ in many ways, but Benjamin also comes off as a “creature” of the living dead. He’s trapped in the non-existence of suburban America of the 1960s, and an environment examined for its undercurrent of “something’s not right” in films like The Pawnbroker (1965) and The Swimmer (1967).

Just as Benjamin goes nowhere in his hometown, Andy has no future, either. How many young men watching both films could sympathize and empathize with Andy and Benjamin? The numbers are likely significant.

How Does a Young Man Become the Living Dead?

Both characters suffered through experiences that turned them into the living dead. For Andy, he becomes a zombie literally. For Benjamin, the notion of being a zombie is metaphorical. His college experience left him with little motivation or practical, real-world experience, so he has no idea what to do once leaving the college bubble. The world lives around him, but he is mostly dead to it.

The ability to connect with their previous lives seems long ago destroyed. Andy’s brief tour of Vietnam and Benjamin’s former tenure at college left them both disconnected. A mystery revolves around both young men. We never find out what specifically made them into zombies. We know Andy met his demise by sniper fire, but we never realize why he comes back from the dead. Similarly, we don’t know the specifics of Benjamin’s experiences during his college years that left him so unmotivated and apathetic.

Perhaps the overarching connection is the environment, itself, contributes to the literal and symbolic deadening. They don’t like where they’ve been nor do they appreciate where they now listlessly exist: home.

So they withdrew.

Both Andy and Benjamin find solace in retreating to their introverted worlds. Andy consistently spends time yearly, rocking in a rocking chair in his room or sitting outside in the sun. Benjamin spends a great deal of time floating on a small raft and his family suburban swimming pool. The external environment means nothing in either scenario, as both men are trapped inside their heads, although Benjamin does experience joy at times. Andy, however, remains in silent misery. Or, at least that’s what we infer. We never see Andy’s fantasies or daydreams like we do Benjamin’s.

Parental Failings and the Consequences

Both Andy and Benjamin arrive home and interact with friends and family. While the families in both films appear festive, both young men seem to keep distance from their families.

The opening setup of The Graduate takes place at a graduation party, and everyone appears to talk around and at Benjamin. They are more self-absorbed with themselves, and Benjamin becomes a foil for commentary. The same thing occurs in Deathdream when the mailman helps himself to food at Andy’s “welcome home” picnic. The mailman never shows interest in Andy. He grandstands and uses Andy as a foil to talk at him.

Annoying party guests aren’t the worse problem. The parenting, in both films, seems lacking.

Andy’s father, Charles, never knows how to deal with his detached son, and we have sympathy for his plight. What person would know how to deal with Andy? Charles is not a psychologist, and Andy’s apparent psychological problems are not issues his father understands how to address. However, Charles’s worst mistakes are not his angry outbursts at Andy. Lying to the police to protect Andy from the police contributes to allowing Andy’s third-act rampage.

Andy’s mother, Christine, continues to make excuses for Andy’s troubling behavior. She’s in denial and makes excuses for his gradually worsening behavior. Christine displays denial at the film’s beginning regarding Andy’s death, and she doesn’t seem to acknowledge he’s a walking corpse at the conclusion. Audiences may maintain sympathy for Christine, as she only wants her son home and her family returning to normal. A refusal to accept something’s seriously wrong with Andy, in part, clouds her judgment. As with Charles, who can say Christine could have done anything to prevent Andy’s homicidal impulses? Likely not, but ignoring a dire problem and allowing it to fester doubtfully leads to anything positive.

The parents in The Graduate have their issues, too. Despite her infidelities, Mrs. Robinson’s garners sympathy as she lost in a loveless marriage to an uncaring, self-centered man. Mr. and Mrs. Robinson do contribute to Benjamin’s “rampage” at the final wedding scene. If Mr. Robinson’s behavior did not affect Mrs. Robinson’s emotional state, she likely would not enter into an affair with Benjamin. The two parents’ “contributory” negligence leads to Benjamin’s “rampage” in the final act. Mr. and Mrs. Robinson face humiliation when Benjamin crashes and annihilates their daughter Elaine’s wedding.

Nightmarish First Dates

Deathdream’s other alternate title Dead of Night, appropriately fits the film’s third act. The conclusion features a double-date that comes off as emotionally dead as imaginable. Andy’s treatment of Joanne, the girl who’s been waiting for him to come home, is cold, distant, and disinterested. When he first reunites with Joanne, she tries to hug him, but he wants nothing to do with her. Refusing to pick up on the cues, his old girlfriend tries to make a meaningful reconnection, but it goes nowhere.

A similarly awful date occurs when family members nudge Benjamin to take Elaine Robinson on a date. Benjamin acts far more aggressively than Andy, but there’s similar intent. Benjamin wants to drive his potential paramour away. Although Elaine attempts to make the date work, Benjamin does everything he can to make her wish never to see him again, shades of Joanne’s evening with Andy at the drive-in.

Both Andy and Benjamin intend to sabotage their dates due to external factors, and both factors involve horrible secrets. Benjamin cannot go out with Elaine because he’s having an affair with her mother. Andy can’t have meaningful relationships with humans because he’s one of the living dead. Repeated meetings would likely expose both secrets, sooner or later. In Deathdream, things happen sooner than in The Graduate, but each character’s secrets become known eventually.

Intriguingly, both films feature dates that involve erratic driving. The Graduate allows Benjamin to scare Elaine to death by driving like a maniac. Deathdream features a rapidly rotting Andy turning psychotic and purposely kills someone while driving with a car.

Driving recklessly could be a metaphor that spans across the two films. The metaphor equates driving recklessly with a life out of control. Benjamin might be enjoying his life, but he’s having an affair with a married woman while ignoring every other aspect of life. Such actions hardly reflect someone on track for great things. Poor Benjamin never sees how he’s being used by Mrs. Robinson and the affair, combined with his wanton recklessness, sets the young man down a troubled path. An obsession with Mrs. Robinson leads him to put his life on hold. Benjamin’s life stops, and he doesn’t realize it.

Andy’s life is more than out of control. It’s ended, and he doesn’t realize it. Consuming blood might keep Andy from physically rotting, but only for the short-term. Preserving his skin from decay only supports the perceptions of “not dying.” Andy long ago died on the inside, as he remains divorced from the living.

To Die to Live, Again and Again

The conclusion of The Graduate involves a symbolic end to life while Deathdream features a true end of life. In both films, lives end literally and symbolically more than once. Andy dies in Vietnam and seemingly dies again at the film’s conclusion. Benjamin’s life appeared headed to an unknown future at the beginning and, while The Graduate’s finale presents an upbeat conclusion, the end also presents ambiguity. Where’s Benjamin going with his life now that he’s upended everything?

Neither ending leaves Andy or Benjamin alone. The final scenes take place in public places. Andy rests by his mother at a graveyard surrounded by the police. Benjamin sits next to Elaine on a bus surrounded by fellow transit commuters. Where are both men headed? We don’t know what the afterlife brings for Andy, nor do we know what the aftermath brings for Benjamin.

Life and death, the literal and symbolic, are truly cyclical in both films. The old life dies for both characters followed by birth and then another ending that leads to something new. Since neither film had sequels, we can only speculate on how the end plays out or continues in a new cycle.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews