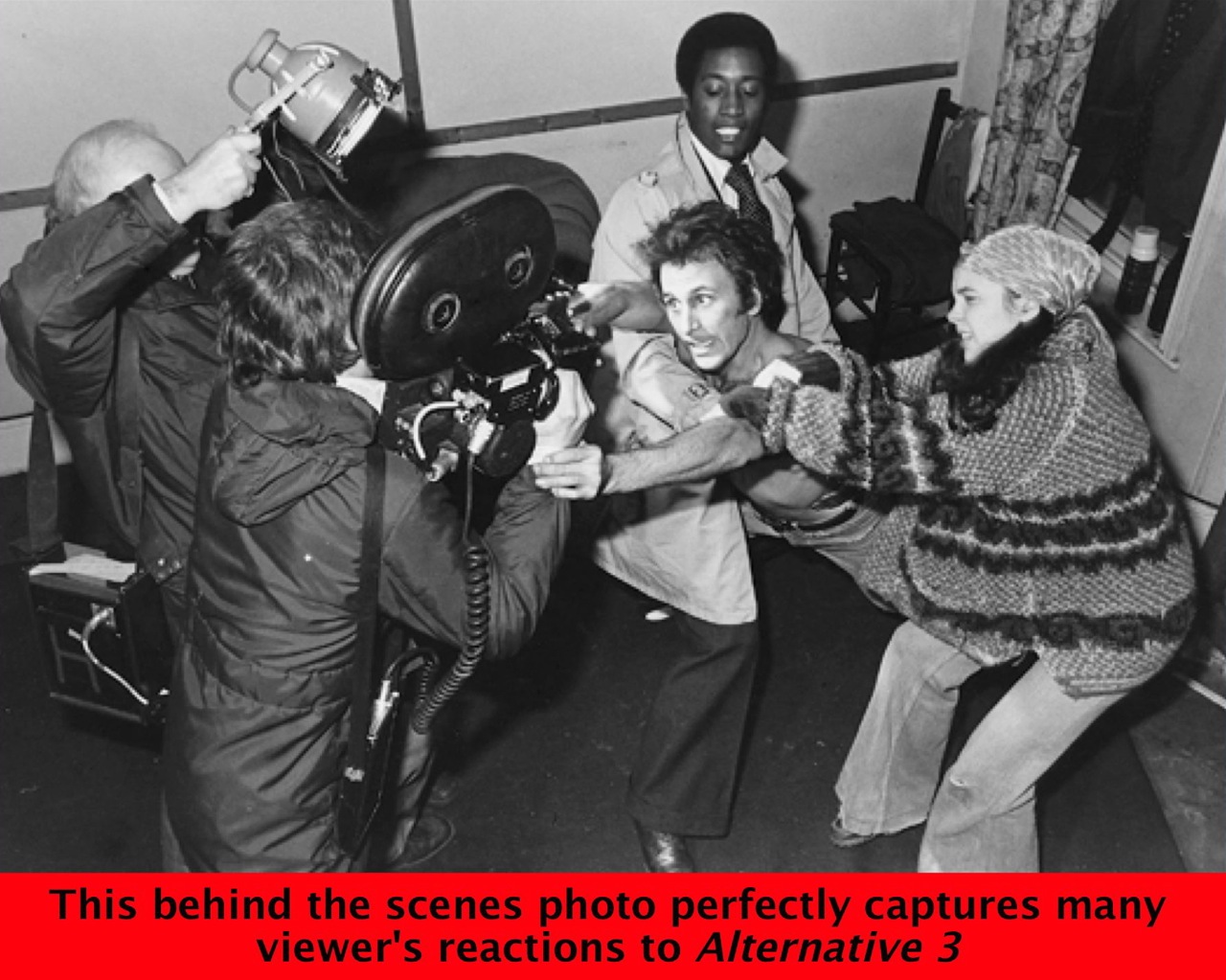

Within minutes of Alternative 3’s broadcast the switchboard at Anglia Television was flooded by terrified viewers convinced they’d seen a genuine documentary; a phenomena that hadn’t been seen since the War of the Worlds radio panic. But while Orson Welles had gone into hiding after his historic broadcast, the makers of Alternative 3 happily faced the public.

As director Christopher Miles recalls, “That night we were on Tony Fish’s BBC Radio phone-in program right through midnight. The phone-in is today a standard part of radio in London, but when BBC Radio London aired the first regular phone-in program in 1977 it was a fresh approach to broadcasting. Tony later sent me a letter, which I still have, ‘Congratulations on the best creative television I have ever seen- sincere thanks Tony Fish.’”

While taking viewer’s calls Miles noticed a very peculiar phenomenon. “During the BBC phone-in dozens of people claimed they saw flying-saucers in the film, proving many people project onto the screen what they’d like to see, not what they actually saw!”

While many viewers were outraged by the broadcast, a few were inspired to try a bit of their own pranking. Christopher Miles shared his favorite piece of viewers’ revenge. “Some people felt it was rather irresponsible to frighten so many viewers. In fact someone got their revenge on Anglia, as the following week Anglia received a phone call from a manager of an old people’s home who rang to report that one of their old timers had died of fright following the broadcast. Anglia rang me in a panic wondering what to do, and I suggested they rang the home first to offer an apology. When they rang the number it didn’t answer the first time, but did the second, as someone had heard the phone ringing from inside a Public Telephone Box and picked it up – gotcha!”

Miles recalls that Alternative 3 even managed to ruffle a few feathers outside the UK—rather important feathers at that. “John Woolf arranged as far as possible back then for the film to be simultaneously broadcast in five other countries. ABC in Australia tagged the program onto its evening news. This upset the prime minister when his aerospace minister asked him if he’d seen the program and then explained the subject matter.”

According to Miles, the furor didn’t end the night of the broadcast. “The next morning we had the headlines of the Daily Express, ‘Storm over TV’s spoof,’ and the front page sub headlines for the Daily Mirror.”

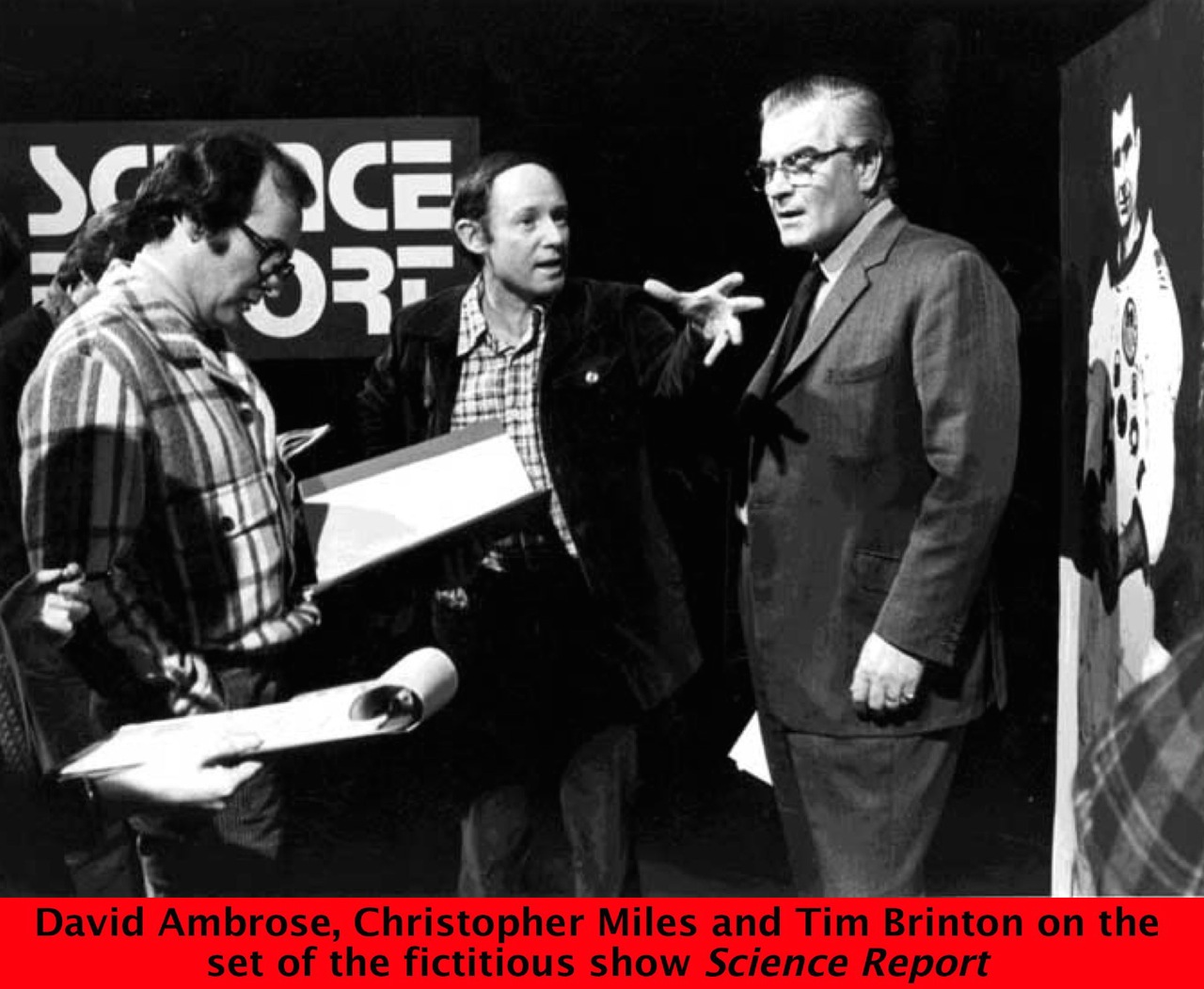

Through all the panic the broadcaster always made it clear that, with the exception of newscaster Tim Brinton, the on-screen journalists and interviewees were all actors, credited at the end of the show. They also reminded viewers that there was no television series entitled Science Report—it had been entirely fabricated for the film. But this reassurance did nothing to dissuade a growing fellowship of true believers, who concluded the actors were standing in for actual scientists and astronauts protecting their anonymity. Despite all of Anglia’s assurances the paranoid seed was planted.

But why did this innocent mockumentary create such a stir? You have to remember that in 1977 the concept of a faux documentary was unheard of. There was still an implied trust between the viewer and the broadcaster that any show advertised as factual would be just that. This kind of unwavering faith has always been fertile ground for hustlers whether they’re well-meaning filmmakers, slick evangelists or Trump University professors. A fake documentary also has one distinct advantage over a dramatic series; while a drama must constantly struggle to suspend disbelief, a fake documentary, particularly one disguised as a legit science show, arrives with belief firmly in place.

This unique power to manipulate viewers wasn’t a surprise to the director. “We really hoped it would cause a sensation, which that night it did. For some time I’d realized that by the means of how you edit a news program you can make the public believe in your ‘alternate story angle’ – ‘fake news’ if you like. But it’s been going on for centuries! Look at the Roman emperors using writers to lie about their conquests.”

Alternative 3 wasn’t the first film to harness the power of the mockumentary. British television had even dabbled in this format before, most memorably with Peter Watkins’ chilling 1965 nuclear war docudrama The War Game. But despite Watkins’ film winning an academy award, the BBC still refused to televise it, deeming it “too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting.” The difference was that, while Watkins’ film was an emotional punch in the guts, Alternative 3 was envisioned as a playful wink to the audience.

Another factor that made Alternative 3 plausible is that it’s so meticulously crafted. Screenwriter David Ambrose cleverly co-opts the dry structure of a British television science show, while slowly weaving a mystery into the proceedings. As the show progresses the filmmakers gradually ramp up more dramatic elements like Brian Eno’s (Roxy Music) excellent electronic score. The puzzle is cleverly pieced together until we have our final revelation—the mysterious, now decoded videotape. Seen today Alternative 3 seems a bit “on the nose”, with too many convenient close ups and cutaways for a legitimate documentary, but that approach precisely mimics the era’s documentary shows.

Anglia Television unintentionally fueled the show’s conspiratorial fire in several ways. The producers originally intended Alternative 3 as an April Fools’ Day joke but Anglia delayed the broadcast for months.

As Christopher Miles recalls, “This was due to the highly complex TV planning between the various broadcasters as to who gets what time slot, and I don’t think Anglia, who were called little Anglia before the show (but not afterwards!) had much clout then. But I also suspect that Sir John Wolff didn’t want to give away the game beforehand.”

Due to outcry from the press and public Anglia decided never to rebroadcast Alternative 3, though it still re-aired in Canada. They attempted to sell the film to American broadcasters but, as Christopher Miles recalls, it was banned for unforeseen reasons. “The tape was given by the Anglia sales team to a woman who I think was named Diane Barclay from one of the major American networks like CBS. One night she showed it to a bunch of friends who were absolutely gob smacked and terrified. Anglia Television calmed her down later but she said on no account could Alternative 3 be broadcast in America. Part of the reason was the FCC’s War of the Worlds regulation (restricting the broadcast of any fictional program that presented itself as factual) but also, as you may know, until very recently American TV documentaries did not have any actors who actually spoke lines.” Miles is referring to a then restriction imposed by AFTRA and SAG—the two American performers’ guilds.

But someone mentioned to the press that Alternative 3 was banned from broadcast in the United States—igniting frenzy among conspiracy theorists who assumed it was being suppressed by some secret government agency. It led to some interesting viewer mail, but nobody involved could have predicted that the paranoid fire would burn brightly for the next forty years.

Don’t miss our final chapter when Alternative 3 becomes the rallying cry for a new conspiracy theory believed by thousands!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews